Politics

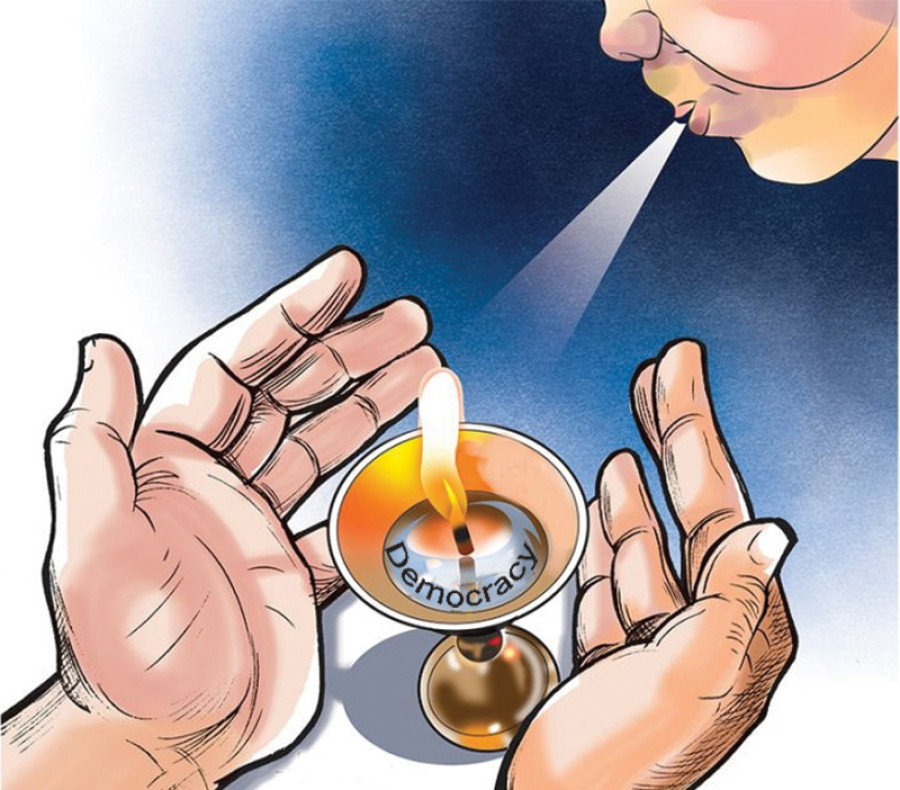

Nepal’s democracy challenges

Analysts say the major impediment to democratic process in the country is a lack of political culture among leaders and their failure to put people first.

Anil Giri

Seventy years ago, on this day (Falgun 7) Nepal ended 104-year-old Rana rule and ushered in democracy. Nepal’s first steps towards democracy, however, were clumsy. It saw five different governments until 1959 when the country held its first general election. The Nepali Congress, which played a key role in overthrowing the Rana regime, was voted to power with a two-thirds majority. Congress’ BP Koirala was elected prime minister. But Nepal’s democracy dreams were short-lived. Just a year later, in 1960, King Mahendra staged a coup, banned political parties and set up a party-less Panchayat rule, a system the monarch said was “suitable to the Nepali soil”.

It took 30 years before Nepal’s political parties could restore democracy that was snatched away by king Mahendra. In 1990, Nepal proclaimed the dawn of democracy. Maendra’s son Birendra was on the throne. Nepal adopted a multiparty system with the constitutional monarchy and wrote a new constitution in 1990.

But Nepal’s fledgling democracy was assaulted once again. This time by Mahendra’s second son–Gyanendra–in 2005. King Birendra and his family were killed in the 2001 royal massacre.

Nepal needed yet another people’s movement in 2006 which abolished the centuries-old monarchy. A Constituent Assembly in 2015 drew up a new constitution, which was promulgated amid reservations from various sections of society. But five years after the new “people’s” constitution, democracy is once again under threat—this time from KP Sharma Oli, an elected prime minister.

As Nepalis mark Democracy Day, to commemorate the historic day of 1951, the country is yet again facing a democratic crisis.

“We have failed to set up a system, especially after 1990,” said Daman Nath Dhungana, a former House Speaker, who was on the forefront of the 1990 people’s movement, which is also dubbed “first people’s movement”. “It’s unfortunate that even a constitution that was delivered by the Constituent Assembly could not establish a political system.”

Many blame a lack of political culture among the parties for why the country has failed to strengthen democracy.

As in after 1951, the Nepali Congress was voted to power after the restoration of democracy in 1990. Democracy hugely suffered because of the growing intra-party feud in the Congress. Despite leading a majority government, then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala dissolved the Parliament and called snap polls. Congress senior leader Krishna Prasad Bhattarai had to face a defeat largely due to the internal conflict in the party.

Disenchantment started to grow among the people, politicians were failing to deliver on their promises despite adopting “the world’s best constitution”.

A section of politicians that was vehemently opposed to the parliamentary system was priming itself for a drastic movement, which would later be known as “people's war”—an armed struggle against the state.

As the governments were formed and pulled down in Kathmandu, the Maoists waged the war in 1996, which continued until 2006. By the time it ended, at least 17,000 people had died and thousands were disappeared and maimed.

In 2001, Nepal grabbed international headlines when Birendra, who now in the hindsight many believe was a benevolent monarch, was killed along with his family. His younger brother Gyanendra succeeded.

People’s growing frustrations with politicians and the ongoing armed insurgency prompted Gyanedra, an ambitious individual with less political and more business acumen, into adventurism. When he staged a royal military coup in 2005, borrowing heavily from his father Mahendra’s over decades-old playbook, Nepal’s ever-squabbling parties made a united front. The Maoists who were looking for a safe landing agreed to lend their support.

The 2006 movement thus managed to extract democracy back from Gyanendra’s clutches. Out of sheer people’s power—widespread demonstrations were held across the country—at the call of political parties, the Parliament was resurrected.

The same year, a historic peace deal brought the Maoists to mainstream politics. The parties agreed to Maoists’ Constituent Assembly demand. But the parties that were together to fight the king once again could not maintain their unity for the larger interest of the public and the nation.

After the first Constituent Assembly elections in 2008, the game of musical chairs began again. The assembly was held hostage to politicians’ petty interests.

It took seven years for the assembly to deliver a constitution–once again dubbed “the best in the world”. The constitution guaranteed Nepal as a secular federal republic.

But five years later, the country is running the risk of losing all those gains and democracy is under threats.

“One of the main reasons why democracy in Nepal has suffered one blow after another is we failed to build institutions and systems,” said Ujjwal Prasai, a writer and political commentator who is also a columnist for the Post’s sister paper Kantipur. “We failed to strengthen and build the system and institutions friendly to the people.”

Prasai is currently an active member of the ongoing civilian protest, being organised under the banner Brihat Nagarik Andolan, to protest Prime Minister Oli’s December 20 decision to dissolve the House.

The Supreme Court is testing the constitutionality of Oli’s House dissolution, as his move has been challenged saying he took an unconstitutional step because the current constitution does not allow him to dissolve the House.

“We consider democracy in a formal context because we are holding elections regularly, we have free press, or there is human rights,” said Prasai. “But that is not enough. A democracy should be able to establish a link with the general public and society. We failed to inject democratic values and ethos in society.”

Nepal’s democratic evolution has also been described by many as one step forward two steps back. When Nepal heralded democracy for the first time in 1951, it was crushed by Mahendra and the country suffered for three decades.

When democracy was restored in 1990, politicians instead of nurturing it, made it feeble, thereby offering Gyanendra an opportunity on a platter to seize power.

Today democracy is under threat from the same actors who once championed for the cause.

Oli has argued that he was forced to take the drastic step because he was being driven into a corner by his opponents, especially Pushpa Kamal Dahal.

In what makes the greatest example of politics making strange bedfellows, Oli and Dahal decided to embrace each other in 2018 with a promise to launch “a great communist movement” that would transform Nepal. Dahal led the decade-long Maoist war, and Oli is among those politicians in Nepal who has always been critical of Dahal.

When Oli returned to power in 2018, it appeared that political stability was finally here to stay. But the factional feud in the Nepal Communist Party, especially between Oli and Dahal, resulted in the House dissolution, in what comes as a repeat episode of 1994 when GP Koirala had dissolved the House over infighting in his party.

This time, however, Oli took the step despite the constitution restricting him to do so, displaying his totalitarian streak, say analysts.

“Earlier political parties had conflicts with the monarchy. Now we are fighting against totalitarian tendencies,” said Dhungana. “Political parties have deviated from their primary duty of nation-building to power-grabbing. In earlier days, it was the palace which had an insatiable desire for power, these days political parties have inherited that tendency.”

During the 30 years of Panchayat rule, power was largely exercised by the palace, with some spoils shared among a handful of royal sycophants.

After the restoration of democracy, just as power was transferred to political parties, Nepal started to see the advent of rent-seeking tendencies. By the time the country became a federal republic, patron-client relationship emerged strongly, corruption became the new cottage industry where politicians and cadres started to go to any extent to exploit state resources.

Analysts say Nepali politicians totally forgot the age-old maxim of the government of the people, by the people and for the people.

“Democracy should serve the aspirations of millions of people and it’s definitely a tall order. That’s why democracy is chaotic also,” said Prasai, the writer. “But by building robust institutions and systems, governments can address people’s grievances and needs. That’s how democracy functions.”

While Nepali politicians are blamed for democratic backsliding, there is a section that strongly believes that until Nepal defeats foreign intervention, it cannot attain stability and cannot make strides in socio-economic sectors.

“The role of foreign hands in every big change in Nepal is no secret–in 1950 or 1990 or 2006,” said CP Mainali, a senior communist leader. “We failed to find the leadership at home that could fight foreign intervention. This is the sole reason we have failed to sustain the achievements in the last 70 years and have not been able to bring changes in people’s lives.”

According to Mainali, once Oli’s mentor, Nepal’s democratic movements have been laudable but a lack of failure to find a true leader has meant people’s aspirations of democracy and development continue to remain unfulfilled.

“We rather allowed more space to foreign hands to expand their clout instead of trying to become strong and independent in our decision-making,” said Mainali. “Our leaders totally failed to comprehend the fact their fight for democracy meant creating an environment where people are served. It’s instead the opposite. It looks like leaders fought for democracy for their benefit.”

Most of today’s leaders in Nepali politics have quite a record of their own under their belts, most of them have served jail terms fighting against the Panchayat regime and then the monarchy. There is no denying that they exhibited their unwavering commitment to democratic values, equitable society and rule of law–and above all, for the people. But the moment they get to power, they tend to forget all these, according to analysts.

“From 1959 to 2006, we were in a direct conflict with the monarchy that always stood against the fundamentals of democracy,” said Prof Krishna Khanal, who teaches political science at Tribhuvan University. “We may have failed to nurture democracy well, but a reversal is unlikely.”

According to Khanal, in Nepal, people's power has always prevailed.

“A democracy also means accountability. The only solution is our managers [politicians] must learn how to manage the system,” Khanal told the Post. “Democracy often faces challenges and we can say it is in peril in Nepal today. But it stands an equal chance of becoming vibrant and functional… just that leaders need to be made accountable.”

Some analysts find an uncanny repeat of a cycle, as people once again are on the streets to fight for democracy, just as the country is celebrating its Democracy Day to mark the dawn of democracy in Nepal.

Prasai, the writer, said that unless political actors are constantly kept in check and made accountable to those who elect them, democracy will continue to face challenges.

“Democracy should be realised by the people, and it’s the political actors who can make this happen,” Prasai told the Post. “In our context, it looks like democracy will face some challenges like it is facing today for some decades more.”

8.84°C Kathmandu

8.84°C Kathmandu