Politics

Almost all major parties have two or more chairs, and that is not necessarily a good thing

While some say collective leadership was instituted to ensure democratic values, others believe it was more of a bid to manage the egos of senior party leaders.

Anil Giri

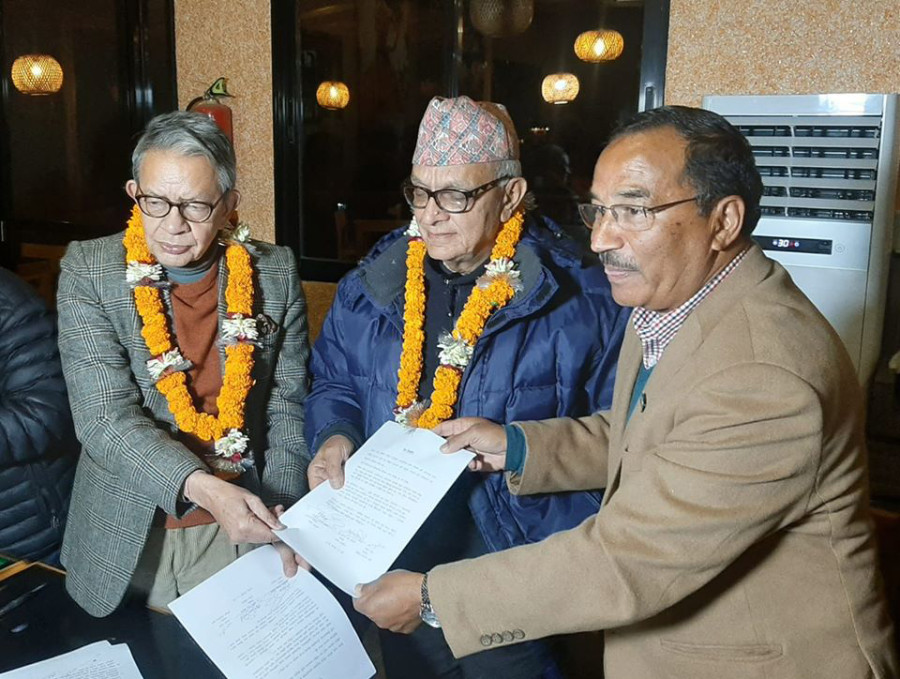

Three chairmen have emerged from the unification of two political parties. On Saturday evening, the Rastriya Prajatantra Party led by Kamal Thapa united with the Rastriya Prajantra Party (United) led jointly by Pashupati Shumsher Rana and Prakash Chandra Lohani. Accordingly, the resulting Rastriya Prajatantra Party now has three presidents, not chairmen—Thapa, Rana and Lohani.

With the RPP adopting a structure with two or more leaders at the top, all of Nepal’s major political parties, except for the Nepali Congress, have now similarly organised themselves.

The Rastriya Janata Party Nepal was the first political party to opt for collective leadership after the unification of six Madhes-based parties in mid-April 2017. All the top leaders of the constituent parties were pulled into a six-member praesidium in the unified party. Although party meetings would be led by a rotating chair, all decisions were to be made collectively.

Following suit, the Nepal Communist Party (NCP), the largest party in the country formed from the merger of the UML and the Maoists in May 2018, also decided to have two chairs—KP Sharma Oli and Pushpa Kamal Dahal.

The Samajbadi Party Nepal, formed from the merger of the Sanghiya Samajbadi Forum and the Naya Shakti Party in May 2019, also has two chairs—Baburam Bhattarai and Upendra Yadav.

According to party leaders, collective leadership has both positive and negative outcomes for the party. On the one hand, it can help provide ownership to party leaders, while on the other, it can lead to factional in-fighting. Party leaders and political scientists, however, agree that the collective leadership structure was not quite instituted to make the party more democratic or accountable, but rather, to manage the egos and aspirations of party leaders who would otherwise constantly be vying for the top spot.

“It was a new beginning for us, but it was not a successful test,” said Rajendra Mahato, one of the six members of the Janata Party praesidium. “It wasn’t a democratic aspiration but simply happened for the management of party leaders’ ego.”

Collective leaderships have almost always emerged in the wake of party unification. As the leaders of the constituent parties are often unwilling to second themselves to another, the structure is put in place to ensure that the entire unification process is not jeopardised, say party leaders.

Thapa of the RPP admitted as much.

“We’ve gone through very difficult phases of division and unification in the past so this time, in order to cement the unification process, we have decided to go for collective leadership,” Thapa told the Post. “We have to look after each other’s sensitivity and if we are able to take decisions practically, it will also establish a sense of ownership.”

However, collective leadership does not always go as planned.

While the Samajbadi Party’s Yadav was health minister in the Oli government, Bhattarai, the other Samajbadi chair, had long been demanding that he quit government in order to demand amendments to the constitution. Yadav eventually did quit government in late December.

Similarly, the six-member Janata Party praesidium remains divided over whether or not to join the government.

The ruling Nepal Communist Party too has not been immune to these kinds of impasse due to differences among the top leaders. Ever since unification, the Nepal Communist Party has been locked in a power struggle between the two chairs. Oli, who is also prime minister, had long managed to sideline Dahal, who was seething at having to play second fiddle for the first time in his political career. Eventually, Oli was forced to allow Dahal to become ‘executive’ chair and look after the party while he handled the government as prime minister.

“Compared to individual leadership, collective leadership has several benefits,” said Narayan Kaji Shrestha, the NCP spokesperson. “In our case, Oli looks after the government while Dahal looks after the party. But whenever any important decision is taken, whether it is related to the party or the government, it usually happens through the Secretariat.”

According to Shrestha, individual leaders have a tendency to become autocratic while collective leadership reflects the true spirit of democratic values.

Shrestha might have been speaking idealistically as Oli has long been criticised by his own party members for running both the party and the government in an autocratic fashion.

Ultimately, if the party is to be run democratically, authority should rest with the party committees, said Shrestha. In the Nepal Communist Party, it is the nine-member Secretariat that ultimately represents collective leadership, he said. This, however, has not stopped the two chairs from attempting to gain a majority following in the Secretariat in order to influence both the party and the government, as has been the case with Dahal’s recent machinations that culminated in the proposal to send party vice-chair Bamdev Gautam to the Upper House.

For Mahato of the Janata Party, who is at the top is not as important as the constitution of the party committees, as it is they who should be running the show. The Janata Party has decided on and off to discard the praesidium at its next general convention, which keeps getting pushed back.

Political analysts agree that simply having two or more leaders at the top does not imply that the party functions collectively, or even functions well; in fact, it could mean the opposite.

“Some leaders need positions at any cost,” said Lok Raj Baral, a former professor of political science. “If they do not get their desired post, they do not agree to unification. In some cases, unifications have been derailed due to self-interest. No one is really fighting for ideology.”

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu