Politics

Contrary to former Indian envoy’s claims, Nepal has consistently raised Kalapani issue with Delhi

Shyam Saran, who served as India’s ambassador to Nepal, said Nepal has been uninterested in seriously pursuing negotiations.

Anil Giri

Former Nepali foreign ministers and diplomats have dismissed the recent claim made by Shyam Saran, former Indian foreign secretary and Indian envoy to Nepal, that the Nepali side raises the issue of the disputed territory of Kalapani for rhetorical purposes, but isn’t interested in serious negotiations.

In an op-ed for the Indian Express published earlier this week, Saran wrote that Nepal doesn’t follow through after raising the issue.

“This is what happened with Nepali demands for the revision of the India-Nepal Friendship Treaty,” he wrote.

The Indian side agreed in 2001 to hold talks at the foreign secretary level to come up with a revised treaty—one that, in the Nepali eyes, would be more “equal” with reciprocal obligations and entitlements, Saran claimed, only one such round of talks has taken place.

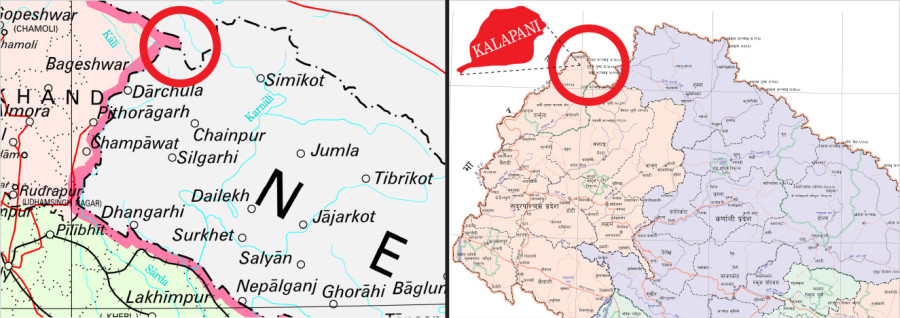

Read: India’s new political map places disputed territory of Kalapani inside its own borders

Since the piece started making the rounds on social media, several Nepali officials have pushed back and challenged Saran’s assertions.

“To put the record straight on Sharan claiming Nepal to have dropped the 1950 agenda from bilateral discussion, it was Sharan himself who lobbied for dropping the Kalapani and 1950 treaty from the joint statement during the 2003 visit of [Prime Minister Sher Bahadur] Deuba to India [sic],” Madhu Raman Acharya, a former foreign secretary who was involved in negotiations with Saran, wrote on Twitter.

Acharya goes further, saying Saran sent two influential Nepali political figures to try to convince him to drop the 1950 treaty and Kalapani from the joint statement issued that year.

“We insisted and managed to keep the agenda alive, thanks also to the wisdom of Prime Minister Deuba not to change Nepal’s position on that,” he said.

In interviews with the Post, several former ministers and diplomats said that Nepal has been consistently raising the boundary dispute in Kalapani since 1963, when Nepal learned that Indians had occupied Nepali land.

Kriti Nidhi Bista, prime minister at the time, was the first Nepali leader to voice concerns over India’s occupation of Kalapani and the abrogation of the 1950 Treaty of Peace and Friendship. After the Indo-Chinese war in 1962, Nepal removed 16 Indian military check posts from various points along its northern border, and from Kathmandu.

“We later came to know that India did not remove its military presence from Kalapani,” said Bhekh Bahadur Thapa, a former Nepali ambassador to India.

Thapa also objected to what he said was Saran’s “threatening language” in his Indian Express article.

“At the moment, raising these issues as means of hoisting their nationalistic colours is of little risk to the Nepali political parties,” Saran said in the article.

Another Nepali diplomat, who served a long stint at the India desk of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, told the Post that Nepal had sent another letter to India in 1968, reminding them that Kalapani belongs to Nepal.

“We have been raising the issue several times through subsequent governmental channels, but they’ve never taken our requests seriously,” said the diplomat, who asked to remain anonymous.

Nepal’s claim over Kalapani hinges on two maps, from 1816 and 1860, jointly agreed and signed by the Nepal government and the then East-India Company.

“Whether it was during the visit of then Prime Minister Manmohan Adhikari to India in 1994 or during the visit of Indian Prime Minister IK Gujaral in 1997, we have been consistently raising the issue of Kalapani,” said PB Shah, a former diplomat who also worked at the India desk in the Foreign Ministry.

In more recent times, according to foreign ministers who have served in the last decade, Nepal has consistently raised the issue of Kalapani, Susta and demarcation of the boundary between Nepal and India.

“When India and China agreed to build a trade corridor via Lipu Lekh, we sent two separate diplomatic notes to New Delhi and Beijing,” said Prakash Sharan Mahat, who served as foreign minister in 2016. “Prime Minister Sushil Koirala himself called up Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to express Nepal’s displeasure over the Indian-Chinese agreement on Lipu Lekh.”

Both Nepal and India had agreed to form a foreign secretary-level mechanism to resolve boundary disputes, including on Kalapani, during the Nepal-India Joint Commission meeting in 2014.

Two years later, Nepal and India also agreed to form an eight-member Eminent Persons’ Group on Nepal-India relations that was mandated to suggest ways to replace the 1950 Peace and Friendship Treaty. Although the report has already been completed for over a year, it has yet to be submitted to the Indian prime minister.

“This essentially shows that Saran’s assertions that Nepal is uninterested in holding discussions are not genuine,” said another former diplomat, who served in the Foreign Ministry. “If Nepal was not serious and did not push the agenda continually, why did New Delhi agree to form two separate mechanisms over our concerns?”

20.3°C Kathmandu

20.3°C Kathmandu