Opinion

‘Panic’ is not a plan

Schools must have clear earthquake response plans

Dronashish Neupane

Over 9,000 schools and 30,000 classrooms were reported to have been either fully or partially destroyed in the 7.8 magnitude earthquake that struck Nepal just before midday on April 25, 2015. Around 1,200 students and 68 teachers reportedly died in the quake. The death toll, nearly four years later, is still hard to grapple with—especially because the warning signs were there.

Nearly two decades ago, the National Society for Earthquake Technology-Nepal (NSET), had issued a poignant warning: In the case of a severe earthquake, 66 percent of the schools in Kathmandu Valley would likely collapse, another 11 percent would partially collapse, and the rest would experience excessive damage. If an earthquake happened during school hours, NSET predicted that 29,000 students, teachers and staff would likely be killed and 43,000 seriously injured. In NSET’s survey of the vulnerability of public schools in Kathmandu Valley, it pointed to the fact that a majority of public schools were in particular danger as they were constructed using weak and ‘traditional’ materials such as adobe, stone rubble in mud mortar or brick in mud mortar. And in 2015, their predictions proved true; Schools built on fragile foundations quickly collapsed in Kathmandu compared to their sturdy and well-built private counterparts.

Disaster risk reduction strategies and steps when it comes to school safety during earthquakes are multifaceted. And yet, our current approaches are limited. With the cautious hope that public schools that fell apart in 2015 have been better rebuilt, it is important to supplement our approaches to earthquake preparedness with a clear earthquake emergency plan. The next disaster could strike during a regular school day.

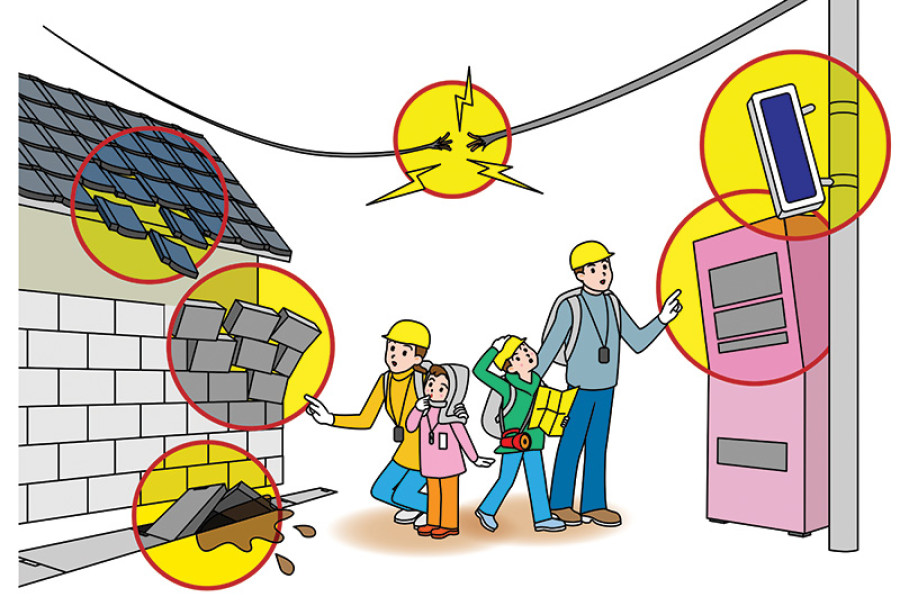

Currently, our approach to disaster management lacks a clear school-targeted response plan. Many schools do not hold earthquake preparedness drills and are not considering the basic requirements of disaster risk safety. For example, the availability of an open space nearby for evacuation is cardinal to ensuring the safety of children after the quake, which unfortunately is not the case with schools, not least in Kathmandu. In Kathmandu, schools grapple with an ongoing space-crunch, which only furthers the risk of damage during disasters. And in grossly erroneous logic, because of the space crunch, many city schools are only expanding their existing infrastructures vertically in a bid to maximise school attendance and enrollment rates. In doing so, the strategy of trying to run down long-winding staircases in a bid to find (virtually non-existent) empty surrounding spaces has become highly dangerous.

This makes the importance of conveying a clear emergency response plan all the more important. According to the Earthquake Country Alliance, official rescue teams from around the world who have engaged in search-and-rescue programs during post-earthquake contexts agree that the ‘Drop, Cover, and Hold On’ strategy is the most appropriate action to reduce injury and death during earthquakes. Contrary to popular belief, they argue that methods like standing in a doorway, running outside, and finding the ‘triangle of life’ are considered dangerous. They do note that the only exception to the rule is ‘if you are on the ground floor of an unreinforced mud-brick (adobe) building with a heavy ceiling’. In these cases, experts suggest that people should try to move quickly outside to an open space.

Either way, it is important for schools to identify the most appropriate response plan for their students and teachers, given the context of their infrastructure and surroundings. It needs to be conveyed categorically to children that they should not ‘duck, cover and hold on’ right in front of school buildings or close to any landmarks if the temblor strikes when they are outside. Students should be well-versed on the various approaches to safety.

School management, teachers, parents, and students themselves must initiate these necessary discussions by advocating for clear response plans. It is imperative that drills are conducted on a regular basis so that when an actual earthquake strikes, the school community can aptly respond to it. These response strategies can begin with mini-classroom drills but should also progress into school-wide discussions and awareness campaigns.

As a teacher, I have conducted numerous drills in my own class. Critics may quickly dismiss such practices as ‘needless exercises’. Many point to the misguided belief that drills do not hold much authority in the event of an actual disaster as everyone is usually succumbed by panic. But panic does not need to be a default response; If students, teachers, and community members are well-versed on their options during an emergency, they can make safer choices and feel more prepared. Knowledge like what to do when an earthquake strikes, where to go after it stops, where to dismiss children (and eventually unite them with their parents), among other concerns, will be very crucial in handling earthquake situations. It is better to have a plan than not.

Neupane is a faculty member at Premier International IB World School.

18.95°C Kathmandu

18.95°C Kathmandu