Opinion

Looking for a home

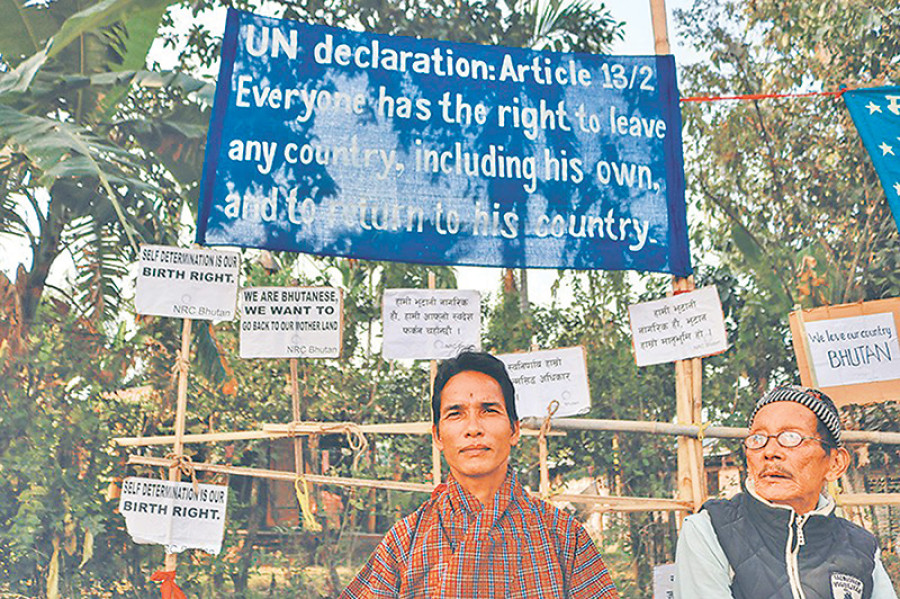

The onus equally lies on the governments of Nepal and Bhutan to repatriate Bhutanese refugees

Tilak Niroula

Following the termination statement of the 26-year-old food support programme by the World Health Organization (WHO), the issue of the Bhutanese refugees has become a heated political issue. While the larger chunk—more than 110,000—had already made their way to the United States and other countries under the UN’s third country resettlement program, 6,600 refugees are still languishing in camps in Nepal desperately looking for some ways to return to their own homeland, Bhutan.

More than 1,641 refugees presently living in camps on a prima facie basis are demanding refugee identity. However, regardless of their registration, the Government of Nepal still has to bear the responsibility of managing food and other essential supplies to the remaining refugees until the issue is resolved for good.

While being mindful of one of the biggest foreign policy failures on resolving Bhutanese refugee crisis despite seventeen rounds of bilateral talks between the two Himalayan nations, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, once again, appears to be rolling his sleeves up to bring an end to the longstanding refugee crisis. The Nepali Premier seems highly optimistic about resolving this issue after meeting with the chief advisor of the then Interim Government of Bhutan Lynpo Tshering Wanchuk during the 4th BIMSTEC Summit in Kathmandu on August 2018.

Prime Minister Oli is vigorously engaged in meeting with the diplomats and local politicians to seek strategies for an enduring solution to the remaining refugees in the camp.

In the meantime, the United Nation High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) too has started collecting the data of those refugees who want to return to their homeland. In the same page, the humanitarian agency had also come up with an idea of collecting data of the people opting voluntary repatriation. Voluntary repatriation, for a refugee, is usually the return of a displaced person who is unable or unwilling to remain in the host country for long and volunteers to return to their country of origin. However, in a returnee situation, this could necessitate a guaranty and provision of national security along with providing for sustainable livelihoods on the part of the country of origin until the long-lost returnees are capable of fending for themselves.

There are also some substantial cases of mixed marriage (Bhutanese man married to Nepali citizen and vice versa) who wanted to integrate locally in Nepal. As such, the Government of Nepal should also look into this situation and start local assimilation by initiating Article 3(1) of the ‘Nepal Citizenship Act 2063 (2006)’, that came into force on 26 November 2006. Children born to a refugee mother and a Nepali father should receive the necessary administrative assistance to complete all the formalities for acquiring citizenship and a needful compensation.

As per a recent survey, around 3,000 refugees living in two refugee camps have expressed their interest to return to Bhutan. Given this, the idea of the local assimilation will narrow down the numbers of dwellers if Bhutan agrees to take the remaining population. Above all, the UNHCR is likely to facilitate the voluntary repatriation process by ensuring peace and reconciliation activities, promoting housing and property restitution, and providing return and legal aid to returnees. Besides these, ensuring that the refugees return to their homelands also demands enduring support of the international community throughout the crucial post-conflict phase so that those who have made the brave decision will be able to rebuild their lives in a stable environment.

Making this possible is the responsibility of both Nepal and Bhutan. PM Oli when he was serving as the Home Ministry was among the major dealmakers during the 17 rounds of bilateral talks between Nepal and Bhutan. Now when he is the executive of the country, one can only hope the same zeal to bring an end to this longstanding refugee imbroglio.

Gross Happiness Index is a unique philosophy that guided Bhutan. But if it is to remain true to it, it has to look after its long-evicted citizens. After all, taking its own people in could also mean a rise in Bhutan’s Happiness index.

What’s more, most of all the refugee intellectuals, frontrunners, and potential leaders have already been resettled in the western world probably for good. Bhutan also does not see any visible threat from any of the remaining refugees in the camp. Although, few of them were left behind for various reasons, many innocent families barely see the prospects of other options other than returning home. Therefore, it appears quite imperative on the part of Bhutanese government to see their patriotic sentiments and open the gate for them.

Four, one of the mutually agreed elements of the bilateral talks—the formation of Joint Verification Team (JVT) comprising of Bhutanese and Nepali officials who were entrusted to determine and verify Bhutanese living in the seven camps started their project on March 26 ,2001. Sadly, it couldn’t sustain even a year after some misunderstanding over the procedure took an ugly turn. In an ensuing dispute, the ‘gho bearers’ abruptly abandoned the project and went home. The JVT couldn’t resume thereafter. Yet, one can easily surmise that Bhutan has at least realised the plight and the long-overdue task needed to be completed under a congenial atmosphere; sooner or later.

Above all, the total solution for Bhutanese refugee crisis lies at a phenomenal behest of burden sharing among the nations involved and Bhutan is a part of it.

Niroula, a former refugee from Bhutan is now a US citizen currently serving on the Youth Services Advisory Board to Mayor’s Office in New Hampshire.

He can be reached at [email protected].

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu