Opinion

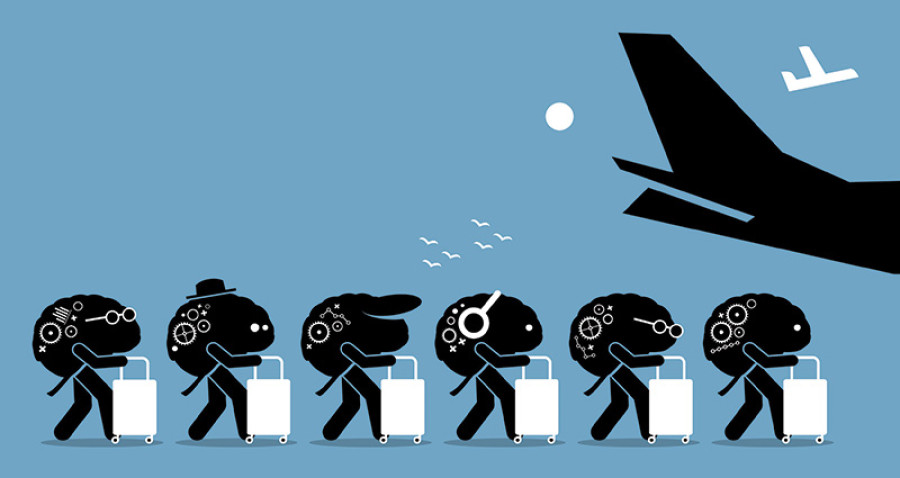

Drain or gain?

Non-structural initiatives can be a productive way to unleash the diaspora’s potential

Dinesh Gajurel & Umesh Raj Regmi

The sheer size of the Nepali diaspora is estimated to be in the millions. If its potentials are untapped, the network, formally represented through the Non-Resident Nepali Association, can become an overwhelming force in Nepal’s development. Keeping all of this in mind, the government has given legal status to the Nepali diaspora by promulgating the Non-Resident Nepali Act 2008. Certainly, institutional platforms are needed both in Nepal (including support from the government) and abroad to foster knowledge exchange and skill development.

This raises the need to establish a mechanism that will help link Nepali academics and the diaspora from various professions will be the Nepal government’s initial step. Except for Tribhuvan University and Kathmandu University, the other nine universities in the country are relatively young.They also lack human and capital resources. Given that, the Nepali diaspora’s role will be cardinal in helping to equip and strengthen the universities to make them desired centres for learning. The diasporic communities can channel knowledge and resources to enhance tertiary education in Nepal.

In this context, it is important to highlight the value of non-structural initiatives. Structural initiatives are more policy driven and formal whereas non-structural initiatives are less formal and of a smaller scale and scope. Creating opportunities for young scholars in Nepal to work together with academics and scholars in the diaspora through an established mentorship programme or network could be a productive example of a non-structural initiative of high value.

The diasporic communities can also commit to aiding the government of Nepal and autonomous universities in vocational education, innovation and exchange programmes, volunteer teaching and facilitation, collaborative publications, redesigning calendars and action plans, and content development for higher education.

Cross-cultural ideas, advanced managerial skills, technology-based teaching-learning, and new expertise and entrepreneurial spirit will definitely help Nepal’s higher education take the leap it has been striving for.

Although the onus for the improvement of higher education remains with the government of Nepal and the universities themselves, diasporic professionals can help to enhance and expedite the process. For this, there need to be appropriate policies, leading to respectable and unpressurised working environments coupled with cooperation between the government and the countries where the Nepali diasporic communities live in large numbers.

More concretely, the government of Nepal should come up with initiatives that will entice Nepalis living abroad to return to their homeland and help build capacity in higher education, especially in the areas of faculty research and graduate teaching. A non-resident Nepali (individually or as a community) can also demonstrate support by helping to build important educational infrastructure such as the construction of libraries and laboratories.

Financial resources could also be extended towards the creation of scholarships for deserving students. Regardless of the form in which this support takes, any support from the diaspora should be for social development and educational contribution rather than for cheap popularity, political benefit, and vested interests.

Regmi is associated with the Nepal Youth Foundation, and Gajurel is an assistant professor at the University of New Brunswick, Canada

14.35°C Kathmandu

14.35°C Kathmandu