Opinion

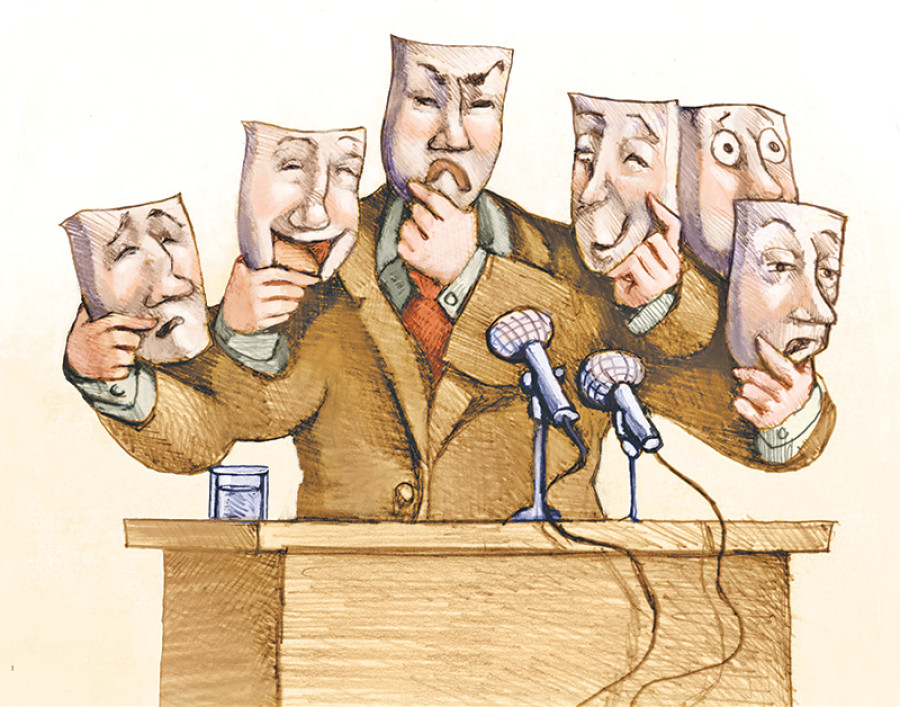

Winners, losers, and posers

In politics, what goes around, comes around. It is the country that loses all the time

Deepak Thapa

My last column had the following sentence: ‘[Prime Minister K.P. Sharma] Oli appears to employ bits and pieces of information he has picked up to prove whatever point he is trying to make.’ The very next day, in agreement with my assessment, he was shooting off his mouth in Zurich. Trying to convince the Nepali community there that there is a ‘Nepali form’ of inclusion, just as we have been told constantly about Nepali versions of everything—from secularism to transitional justice to now foreign policy—Oli said: ‘The situation of inclusion in Europe and Nepal is different. Europe was created out of one land, one ethnicity, one language. We are a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-cultural nation.’

Thus spake our prime minister, just months after a nearly all-black team of French footballers had lifted the World Cup, while our closest European pal, Britain, welcomed a mixed-race princess and also got a Home Secretary of Pakistani origin. Or, perhaps, Oli meant it in the historical sense. In which case, our prime minister either has no inkling of the immensely gory history of Europe, much of it driven by real or perceived differences along every parameter conceivable, or he subscribes to the casually racist view: All kuires look alike.

This piece, however, is not about Oli, not completely at least. Actually, I was struck by the first sentence of his remarks to the Swiss Nepalis. When he began with, ‘We all know why we came here, and in what context,’ the first thing that came to mind was he was going to talk about the unfortunate in-country circumstances that had forced the Nepalis there to seek a life elsewhere, and so on. The next two sentences, however, were a downer since it was clear he was referring to himself and his entourage being in Davos.

The Korean story

The reason I thought something more profound was in the offing during the Zurich interaction was because I had been immediately reminded of the somewhat well-known 1964 visit to West Germany by the South Korean president, Park Chung-hee. Having arrived to negotiate a loan, Park took time off to meet a group of Korean nurses and miners in the Ruhr region. The decade after the end of the Korean War (1950-53) had seen the country struggling to stand up after war-time devastation and privations all around. According to the newspaper, Chosunilbo, there were only 54 companies employing 200 or more people at the time; and the Gross National Income (GNI) per capita income was around $120 (Nepal’s was $50). One of the ways South Korea adopted to deal with this problem of small economic base and rising unemployment was through the time-honoured tradition of labour migration. Among the first of the migrant workers were those nurses and miners in Germany.

As Chosunilbo writes: ‘On Dec. 10, 1964, some 300 miners and nurses gathered in the hall of a mining company…[T]he last part of the Korean national anthem, which was played by a band of miners, was barely audible because everyone was sobbing. Park stepped up to the podium and began his speech. “Let’s work for the honour of our country. Even if we can’t achieve it during our lifetime, let’s work hard for the sake of our children so that they can live in prosperity like everyone else,” said Park in a speech that came to an abrupt end when he choked up as well. Everyone cried, including the first lady and the officials accompanying the president.’

There is a version that says that the Korean workers in Germany put up their future earnings as collateral for the German loan. Whether that actually happened or not, the South Korean miracle is there for all to see, having achieved developed country status in a quarter of a century. Critics point out that the rapid economic growth was possible only at the cost of the human rights of the workers who fuelled it. And, leading it for the first two crucial decades was Park, a sometimes ruthless dictator whose legacy even tarred his daughter, Park Geun-hye, during her own presidency.There is no doubt though that the children of the nurses and miners in the hall that day were certainly prosperous. Between 1962 and 2017, the country’s per capita GNI increased more than 236 fold to reach $28,380 (Nepal’s rose by 16 times to $800). From the 1950s to the mid-1980s, South Korea was a net exporter of workers, and, now, people from countries like Nepal vie hard for a chance to work there.

It is the achievement of countries like South Korea that give our ruling party leaders the confidence to claim that it is possible to believe in their slogan, ‘Prosperous Nepal, Happy Nepali’. Whether they can emulate Park in the long run remains to be seen. In Zurich, Oli did his best to convince the Nepalis there that things were moving in the right direction. But, then habit appears to have taken over as he lapsed into this strange aside while criticising the EU restrictions on Nepali airlines: ‘Our friend, France, has sold us two Airbuses. It was sold saying it can land in Kathmandu, and also fly from there. Their Airbus was sold because it can land as well as fly. But, when we say we want to bring it to your airport, they say: “No.” That’s some kind of weird restriction. They sold it to us saying it can land in our airport. They have also agreed that it can fly from our airport. But, if we say we want to bring it to an airport in France, that’s not possible they say. Is it our airport that is useless, or our sky that is useless, or France’s…difficult to understand.’

I am sure those remarks got a fair share of laughs as any address by Oli does.Whether they succeeded in creating a bond with his audience as when the former general, Park, sobbingly empathised with his compatriots’ plight half a century ago, I have my doubts. The reason the Park episode is so powerful is because just by reading about it,one can actually sense the depth of feelings on both sides.Of course, the onus for Nepal’s progress lies not only on the prime minister but all of us who perhaps do not feel the same way about the nation as the South Koreans did after a war for their very survival. But, perhaps it also takes a different kind of leader to rouse a country into action, not a comic raconteur.

Habitual tendencies

Without doubt, there are many obstacles facing the country. Writing in Himal-Khabarpatrika, former Finance Secretary Shanta Raj Subedi wondered why foreign investment is proving so elusive despite all the policy reforms undertaken. Apart from the fact that Nepal ranks low in the World Bank’s ‘Doing Business’ index, having slipped five places this year, Subedi surely knows what ails Nepal otherwise as well. In case he did not, there were two others writing in the same issue ready to enlighten him: Shekhar Kharel identified crony capitalism; and Dipak Gyawali, the entrenched rent-seeking culture.

The latest news that Nepal went down in Transparency International’s corruption perception index shows where the main problem lies. Park Geun-hyeis in prison serving a 24-year sentence for influence peddling. Even though our anti-corruption legislation is very clear that influence peddling is a form of corruption, I cannot remember anyone even being charged with that crime in Nepal, ever. You can have the best laws in the world but if corruption trumps everything, we get stuck with insidious practices such as crony capitalism and rent-seeking. And, yet we continue to bemoan the lack of interest by foreign investors.

On the political side, all our leaders are capable of is fake indignation. Witness the spectacle of Nepali Congress activists adopting the Airbus purchase issue to hammer the ruling party with. Back in the early 2000s, UML cadres took over the streets of Kathmandu for weeks on end against the Lauda Air scandal that had implicated the then Nepali Congress government—to no avail. In politics, what goes around, comes around. It is the country that loses every time.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu