Opinion

Growing money

It’s time we realise the economic potential of the medicinal plant sector

Carsten Smith-hall & Dipesh Pyakurel

The World Bank has underscored that Nepal is stuck in a low-growth trap. The ongoing large-scale outmigration occuring in Nepal is a symptom of the chronic problems that continuously hamper intiaitves to create more employment opportunities at home.

While remittances are useful for individual households and communities, outmigration decreases the pressure for creating new in-country jobs and does not contribute much to improving public service delivery—for example, in health or education. On its current path, the World Bank and others strongly doubt that Nepal will achieve the government’s target to graduate towards ‘lower-middle-income country’ status by 2030.

The government and other institutions have pointed to a number of ways to break out of the low-growth trap, but has the current spate of initiatives overlooked important possible contributions? The answer is yes.

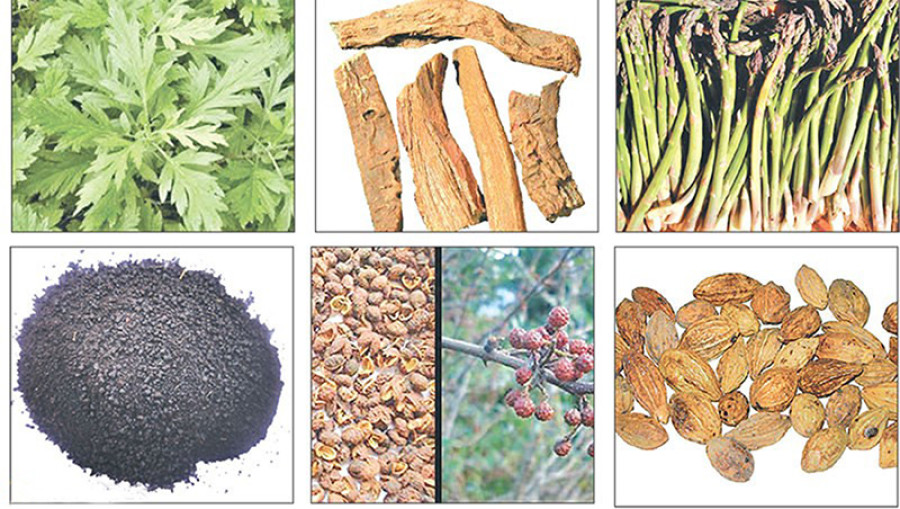

Every year, commercial medicinal and aromatic plants are harvested throughout Nepal. Trade encompasses products from hundreds of species—from fruits to roots, leaves, and bark. The annual trade market is far from minute; beyond the annual

value of tens of millions of USD, the market also amounts to over ten thousand tonnes of goods and involves hundreds of thousands of collecters, traders and wholesellers.

In a recently published paper by the authors of this piece, it was found that trade in medicinal plant products in far-western Nepal in the past two decades has doubled in volume and increased 17 fold in value. And at a recent conference in Kathmandu on wild plant harvests in Asia, a string of evidence was presented that indicates the economic importance of unprocessed medicinal and aromatic plant products to households and communities throughout Nepal. The rises in volumes and values appear driven by increasing demand in China and India and facilitated by expanding infrastructure in Nepal.

While commercial medicinal plant resources are a substantial asset that appears to offer opportunities for economic development in Nepal, the economy-wide potential of the sector is far from realised. There is ample scope for the government to contribute to increasing the economic returns from this trade, to the benefit of harvesters, traders, processors, consumers, and the government coffers. The above mentioned far-western research paper provides insights into specific ways forward. Here we emphasise three independent steps that can make large immediate differences, especially targeting poor and marginalised producer households and communities.

First, responsible government institutions, such as the Department of Forests and Soil Conversion, should proactively handover the management responsibility of alpine meadows to local communities in non-protected areas. Harness the best outcomes from the sucessful community forestry experiences generated by many development intiatives around the world and replicate it for alpine meadows.

This technically simple intervention would promote sustainable commercial harvesting of medicinal and aromatic plants. Community forestry has been a great conservation success; large-scale implementation of this handover intervention is mainly a matter of political will.

Second, in a related point, is the necessary removal of exisiting policy measures that have been proven their ineffectiveness. Bans on collection, trade, and export merely support the flourishing of a ‘trade underground.’ For example, lichens and panchaauleare continue to be traded even though they have been banned from commercial exploitation for years.

Providing harvesters with incentives to sustainably manage such species by equipping them with the required resources will enable more intentional, conservation-oriented approaches to economic growth. Another important policy intervention would be for the government to work to dismantle the trade barriers erected in India, such as the limitation on species that can be moved through Uttar Pradesh. Such barriers drive up costs and limit competition among wholesalers in Nepal, distorting the market to the disadvantage of producers. Only the government can pursue these changes in India—the task is beyond any actor in the production network.

Third, investments in knowledge creation and sharing should be targeted where they matter. For example, invest in the currently scarce research funds to focus on accumulating the production of Nepal’s Himalayan species such as jatamansi and kutki, as Nepal is their primary global producer. By focusing on what we have rather than investing in lowland speciies that can be grown more competitively in other places, we can more effecitively repurpose our production efforts in more intentional and less wasteful ways.

In another example, Nepal could collect, create and disseminate knowledge on domestication technologies, such as forsatuwa or kakoli, as their prices are sky-rocketing and conseqently making many farmers keen to integrate their cultivation into the exisiting mixed agricultural production systems.

Implementing these changes would allow farmers, entrepreneurs, and Nepal to gain from the growing demand and markets, utilising one of Nepal’s few productive competitive advantages. This could provide the starting point for basing economy-wide economic growth on the commercial medicinal and aromatic plant sector, making a concrete contribution to breaking out of the low-growth trap.

Smith-Hall is a professor in the Department of Food and Resource Economics at the University of Copenhagen. Pyakurel is a PhD scholar at the Agriculture and Forestry University and the University of Copenhagen.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu