Opinion

Principia fallacia

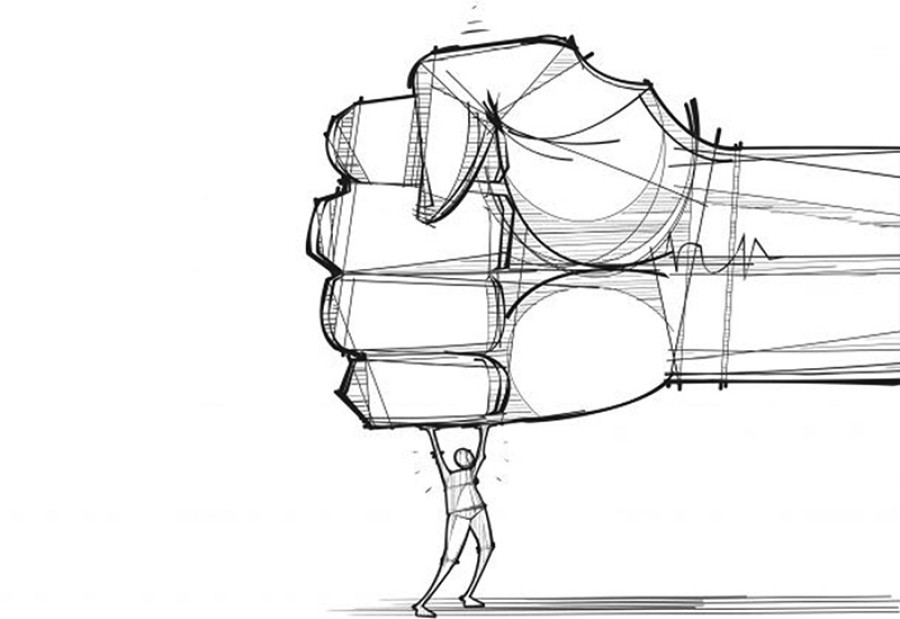

The PM’s extreme hubris and incessant penchant for principles of fallacies is failing the nation

Achyut Wagle

In a live television talk show last week, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli contented that the theory of gravitation was not first discovered by Sir Isaac Newton in the 17th century but 500 years before that by an oriental sage Bhaskaracharya (II).

It is true that Bhaskaracharya conceptualised gravity in his treatise Surya Siddhant, by stating ‘Objects fall on earth due to a force of attraction by the earth. Therefore, the earth, planets, constellations, moon, and sun are held in orbit due to this attraction’. However, the computational precision of the concept by Newton, who penned Principia Mathematica, helped advance the field of science tremendously, and no other concept has arisen to challenge it.

Oli’s comparison was absolutely unnecessary. It was a feeble attempt to draw home his point that there is a ‘huge’ prospect of generating electricity from gravitational force. An initiation of such an arcane development discourse in Nepal, a country that is unable to harness even readily available abundance of hydropower for example, by none other than the chief executive of the nation, was nothing but a deliberate circumvention to deflect the public attention away from more pressing problems the country presently faces. More than that, it is a dangerous sign that exhibits a complete disconnect our country’s leaders have with the country’s immediate development and the government’s needs.

Crisis galore

The governments at the centre as well as in provinces are all powerful with an almost unprecedented popular mandate. Elected office-bearers in all 753 local governments are in their seats for more than a year now. After a very long time, there is a sense of political stability. But, despite these desirable fundamentals for economic growth, physical development and improved public service delivery in place, the country’s economic indicators points to an increasingly precarious situation.

The budget for the current fiscal year was presented on a constitutionally stipulated date (May 28) and was timely ratified by Parliament. But this alone does not seem to have improved the disbursement and government procurement practices as evidenced by the meager 5 percent of allocated capital expenditure in the entire first quarter of the fiscal year. The phenomenon has obvious consequences on overall development outcomes. More than that, government’s inability to spend timely has other multifaceted unwanted impacts on the economy.

The country’s financial system has already started to feel the heat of an impending liquidity crisis. It is certainly a familiar seasonal story to our ears. But, unlike previous years, when the effect used to be felt towards the middle of the fiscal year, in January-February, this time around, the problem has surfaced much earlier. It is therefore likely to have telling constrictions on the growth and well-being prospects. The crisis is already more acute than generally thought. A lack of loan-able capital in the financial system, despite the central bank’s expansionary monetary policy at a high cost of systemic risk, is not at all a commonplace story. The government has failed, first to understand that, given the political stability, the demand for bank credit by the private sector would substantially increase and, second, to manage additional or alternate sources of funds to meet these demands. It has put both, the corporate governance of the financial system and government credibility, at serious risk.

Failing federalism

The federal government’s largely mollified and dictatorial intentions to not decentralise power to sub-national and local levels in the true federal spirit are by now apparent. One of the key reasons for the government’s lackluster performance is primarily due to this blatant disregard to federal facade and decision autonomy to lower layers as inherent in federal polity. The provincial governments are lurching in limbo, and are therefore gradually being rendered ineffective. The centre, clearly at the behest of the PMhimself, has decided not to listen to any of the demands, concerns or complaints of the chief ministers (CMs). All CMs, due to feudalistic subservience to Prime Minster Oli and six out of seven’s allegiance to the same ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP), have failed to effectively put forth the problems faced by provinces in advancing developmental endeavours. They too seem to have opted for proverbial ‘hedonistic escapism’ instead of locking horns with the ever-obstinate prime minister.

So much so, the PM personally appears averse to holding the Inter-State Council meeting as provided by Article 234 of the constitution. The Council, designed to sort out contentious political issues between the centre and the provinces, comprises the PM and the CMs along with a few other federal ministers. The first meeting, called for on September 10, was abruptly cancelled owing to the whim of the PM, after all CMs had already landed in Kathmandu for the purpose. The grapevines have it that PM Oli is extremely reluctant to organise this meeting because he is aware that the CMs are determined to demand for an appropriate political atmosphere so as they can exercise effective authority given by the constitution whereas the PM is not willing to budge. The major roadblock on the effective implementation of federalism is caused by utter disinterest of the federal government to put required legal and institutional frameworks in place. Several laws and by-laws are yet to be drafted. The administrative structure and personnel management to local levels is still in uncertain transition and institutions like Natural Resources and Fiscal Commission are not formed, for no apparent reason.

Local pain

No doubt, with federalism, some funds and some degree of autonomy have been funneled to local governments. But, due to three major bottlenecks, which could perhaps be solved only by honest intentions and support from the federal government, the effectiveness of the local governments has also been affected. First, although local levels though became ‘governments’, their lack of skill in public financial management is limiting their expending ability. Second, the capacity of the elected officials to manage the development projects in their entire cycle is understandably limited. Trained bureaucrats needed to support the cause are not present at those sites. It is also adversely affecting the prioritisation of the public goods provisions in those jurisdictions. Third, the transparency and accountability mechanisms do not, literally, exist at the local levels. This, on the one hand, is leaving room for the public officials to indulge in policy adventurism like an ad hoc collection of taxes and fees, and, on the other, they risk soon being embroiled in corruption scandals making the local levels new havens of financial irregularities.

PM Oli, technically and morally, is at the centre of all these ominous trends. Everybody, including Oli’s erstwhile loyal supporters, is now convinced that his extreme hubris and incessant penchant for Principia Fallacia (Principles of Fallacies) over Principia Mathematica as exhibited, symbolically, in the recent Bhaskaracharya episode, is failing the nation. Given his self-righteous and arrogance-fortified personality, nobody seems ready to ‘bell the cat’, leaving him alone to meander in the entire power corridors of Singha Durbar.

14.24°C Kathmandu

14.24°C Kathmandu