Opinion

Stirring up a hornet’s nest

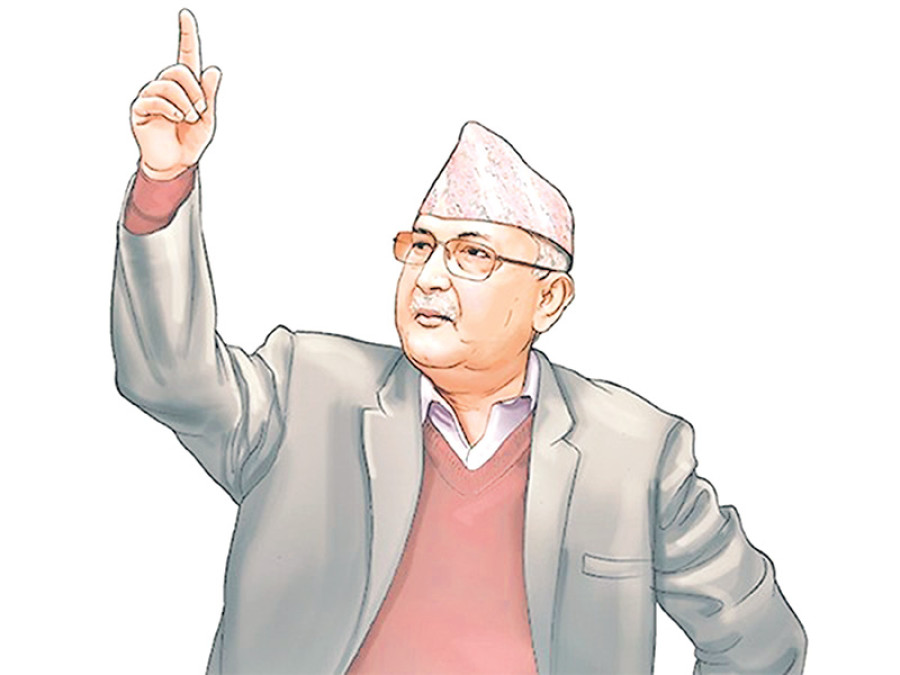

Oli has shown himself as a dreadful ‘queen’ hornet sitting at the centre of everything

Achyut Wagle

The Nepali media and social media both are flushed with Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli’s ‘attack like a swarm of hornets’ diktat. Last week, in a signature communist dictator’s fashion, he ‘officially’ provoked his cadres to attack the critics of his government like a swarm of hornets. It amply indicated the modus operandi the government would adopt in the days to come—stiffening itself not to listen to criticism in any form, neither fact-based nor constructive, and thereby, improving or altering its course of action accordingly in a true democratic spirit.

As such, Oli has implicitly personified himself as a dreadful ‘queen’ hornet sitting at the centre of everything, which perhaps aptly depicts his increasingly solidifying persona of an utterly dysfunctional but highly vindictive one-upmanship. The prosperity agenda which Oli as prime minister so much harped on is completely thwarted not only due to a series of botches and bad governance, but also his obstinacy, totalitarian motives and sheer hubris. Such bungling and faltering now encompass every aspect of the affairs of state—primarily law and order, rule of law, federalism and the economy.

Low investment

Nepal deals with a chronic problem of low investment. The major concern for every potential investor, domestic or foreign, has persistently been the country’s precarious law and order situation. The dangers of extortion, murder, rape and violence have substantially increased over the years. The situation is exacerbated by increased incidences of impunity, collusion of investigating agencies themselves in organised crime and protection of criminals by major political parties, very often by the incumbent one. The current government has added two ominous dimensions to it: First, like in the Nirmala Pant rape and murder case, a few powerful ruling party leaders are making substantial efforts to protect criminals and those responsible for destroying evidence at the crime scene, purportedly at the behest of the former. Second, the government is stretching its long arms to the judiciary to influence the verdict on cases crucial to its interest.

Over the years, institutional degeneration of the security forces like the Nepal Police has been appalling. In every large scale organised crime, from gold and foreign currency smuggling to covering up or distorting murder investigations, the direct involvement of crucial police officers with vested or self-interests now appears to be a commonplace incidence.

The current pervasiveness of impunity is also an extension of the failed state syndrome. It mainly resulted out of a failure to bring to justice the perpetrators responsible for an extensive range of crimes against humanity during the decade-long insurgency, both among governmental security forces and Maoist guerrillas. The truth and reconciliation process has hopelessly collapsed. The former Maoist faction, now integrated into the ruling Nepal Communist Party (NCP), is reluctant to allow an impartial investigation into its rank and file and so are the security forces of the country. As the military mastermind of the Maoist insurgency era now heads the all-powerful Home Ministry, the interests of both sides to abort the truth and reconciliation process have converged.

Recent episodes of arresting journalists even without an arrest warrant by invoking flimsy allegations like cyber law, deboarding foreign-bound nationals perceived to be critical to the government at international forums, and making dozens of other politically vindictive overtures exhibit an infringement of the very concept of the rule of law.

The democratic credentials of the government have eroded so seriously that not only are opposition politicians, the media and civil society sensing the threat, but NCP functionaries, who beg to differ with Oli’s cronies and henchmen, have also been indiscriminately targeted. The Kathmandu elite was awestruck when Shambhu Shrestha, editor of Dristi weekly, which, despite being a supposed mouthpiece of the ruling party, has been critical of the Oli government for some time now, was summoned by the police for publishing a news item last week alleging involvement of some influential members of the NCP in a controversial real estate deal. Increased numbers of such instances where the state selectively chooses to penalise at its will and when jurisprudence is tardy, if not compromised, no new investor is likely to be attracted to Nepal. But prosperity without investment and increased productivity is, without saying, a mere mirage.

Faking federalism

Last week, the chief ministers of all seven provinces gathered in Kathmandu for the first Inter-State Council meeting. Article 234 of the constitution contains a provision for the Council ‘to settle political disputes arising between the federation and a state and between states’. It is chaired by the prime minister with all chief ministers and federal home and finance ministers as ex-officio members. But Prime Minister Oli cancelled the meeting at the last minute out of his personal dislike for a meeting with the chief ministers in Pokhara a day earlier, which resulted in a nine-point demand exposing the central government’s ‘anti-federal’ behaviour and practices. It is apparent that without addressing the concerns and issues raised by the chief ministers and institutional and operational bottlenecks faced in implementing federalism, the polity is absolutely unlikely to move ahead. When meetings between the chief ministers and the prime minister are made impossible, cosmetic praise for federalism will only add to the problems of the people instead of solving them.

The country’s economic future is inextricably twined with the success of the federal polity. The very idea of federalism is underpinned with the principle of creating ‘sizable’ and ‘multiple’ economies within a national economy. But when the federal government is unwilling to devolve power under any pretext, coupled with threats and anger as shown by the prime minister, and when provinces are still treated as pure subordinates of the centre, the very philosophy of federal polity as partially shared sovereign authority gets annulled. The economic as well as political consequences of such an eventuality are bound to be horrific, the direction which Nepal is gradually heading to.

The current government is stirring up a hornet’s nest of a far larger size than Prime Minister Oli had wanted to contain his critics and opposition. Sadly, for his dwindling credibility as the prime minister, his ‘worker’ hornets have instead begun to ridicule him rather than responding to the call for attack.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu