Opinion

Understanding sexual consent

There’s only one way to know for sure if someone has given their consent: if they tell you

Anjam Singh

The recent #metoo movement has provided the global evidence of the startling magnitude of sexual harassment and misogyny especially experienced by urban and educated women. Aptly, it opened up a discourse on the ubiquity of violence particularly sexual harassment faced by women across diverse class, caste, race, religion and profession. The movement has also contributed to mainstreaming the discussion on sexual harassment and violence which was earlier considered the responsibility of only feminist activists Such mainstreaming of discourse on sexual harassment against women has raised concerns among certain sections of men as well as women who argue that the constant fear-mongering among men about their behavior would negatively affect their everyday interactions with women. I raised this issue following a discussion with some of my male friends who raised concerns over the thin line of affection/flirtations and harassment which could be easily misconstrued, difficult to decipher and at times, misused. Perhaps the concern is over-hyped and it largely stems from the lack of understanding of consent and how it works.

Ambiguous understanding

The case of Aziz Anasari represents an excellent example of the ambiguous understanding around consent. The American comedian of Indian origin, was publicly accused of having forceful sexual encounter by one of the girls he dated. The incident caused a huge uproar and divided opinions even among feminists, some of whom opined that such issues should not be conflated with the serious issues of sexual harassment and rape that #metoo movement had been raising.

At the same time, the voices sympathetic to Ansari stated that he was unnecessarily being demonised as it was just a case of “relationship gone wrong.” They argued that the nature of their interaction was largely consensual and the girl should have given clear indications of resistance if she was being uncomfortable or forced to do something she didn’t want to.

While this incident may not be, as some feminists argue, as severe in nature as rape or other forms of violence against women, this doesn’t discount the need for speaking up against and calling out these kind of behaviors. Not speaking against them would further normalise the widely prevalent and deep-rooted patriarchal behavioral patterns that i) consider sexual pleasure being only men’s domain, ii) disregard women’s opinions/decisions on matters related to sex and intimacy; and are devoid of sensitivity to gauge discomfort faced by the other party.

Further, the incident has opened up the discussion on what exactly consent entails and how we understand harassment and violence in the seemingly consensual relationships and interactions better.

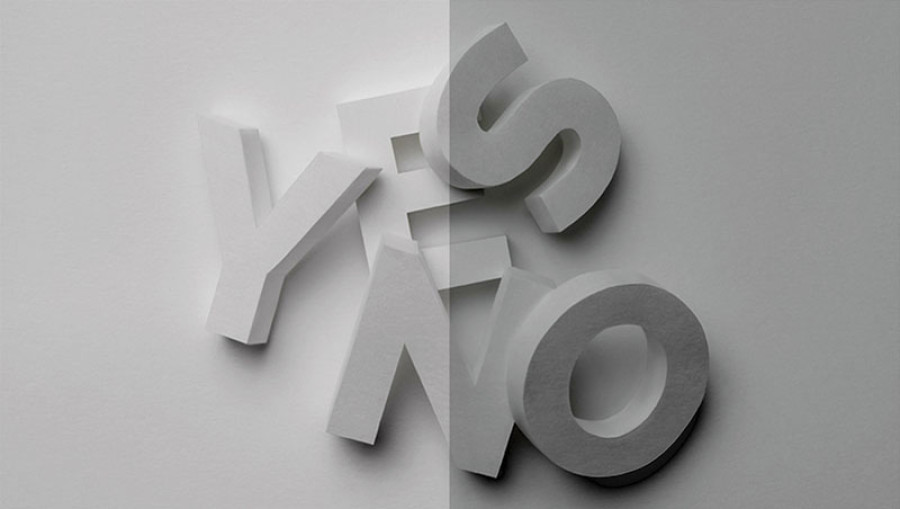

Over the years, the discussion of sexual consent globally has moved from a position of “no means no”—which highlighted that one of the parties have to show some forms of resistance to express lack of consent- to “yes means yes” which requires both parties to express conscious, voluntary, verbal or non-verbal agreement to partake in any activity of sexual nature. The shift from no means no to what is now called an affirmative consent

Hold accountable

The Gender Equality Act 2006 of Nepal has also revised the definition of consent in section 14 of Muluki Ain to include the concept of affirmative consent in the context of rape. The revised definition states that consent given by a minor; acquired through fear, threat, duress or coercion or by subjecting her to an undue influence shall not be deemed consent. Similarly, consent acquired in the state of unconsciousness is also not considered consent.

The Gender Equality Act has also expanded the definition of consent in the context of sexual harassment recognising marital rape as a criminal offense. While these laws are progressive, concerns and confusion remain how these laws can be effectively implemented and how the notion of consent can be further expanded to incorporate complexities pertaining to sexual interactions particularly in marital or intimate relationships.

In addition, the patriarchal attitude of institutions of justice is often the biggest hindrance to translating the laws into practice. In the absence of adequate understanding of gender and power relations, laws dealing with sexual harassment/rape and consent are, in most cases, interpreted in such a way that discount victims’ experiences. Moreover, if the accused is someone known by the victim, the instances of violence are further trivialised and the onus of preventing the violence is often put on women.

The high-profile case in India in 2015 involving a film-maker highlights this pattern. Mahmood Farooqui—an Indian filmmaker was accused of rape by an American scholar, who was an acquaintance and had traveled to India for her research study in 2016. The two had shared some level of intimacy in the past however, on the day of the incident, the victim claimed that she had refused sex and had resisted both verbally and non-verbally however, the accused forced himself on her.

Her claim of resistance was verified by the trial court and the accused was initially sentenced to jail for seven years on the charges of rape however, the Delhi High Court acquitted him saying “instances of women’s behavior are not unknown that a feeble no may mean a yes” Implementation is key. This judgement shows that just having progressive laws on violence against women does not always translate into justice. This judgement did not take into account the complexities of consent that saying an emphatic “no” in the face of sexual violence is not always possible especially if it involves somebody they know because of fear of consequences, intimidation or because they are just too shocked by the betrayal of trust.

While the definition of consent in the Indian Penal Code 375 explicitly mentions that consent has to be expressed through words or overt actions and that silence or absence of no does not automatically amount to consent. Many feminists also argue that the judgement does not consider the fact that the prior relationships or sexual interactions do not set the ground to justify consent and consent has to be taken for the present interactions. Similarly, consent also needs to be taken for a particular sexual act.

We have progressive laws but still attaining justice for women remains an uphill task. We should be critically questioning the taken-for-granted and trivialised patronising, objectifying, dehumanising and violent behaviors and actions against women. Most importantly, it calls for a redefined relationship between women and men at all levels that is based on equality and mutual respect towards each other’s decisions and opinions. It isn’t a difficult thing to ask for, is it?

Singh is a freelance social science researcher

18.95°C Kathmandu

18.95°C Kathmandu