Opinion

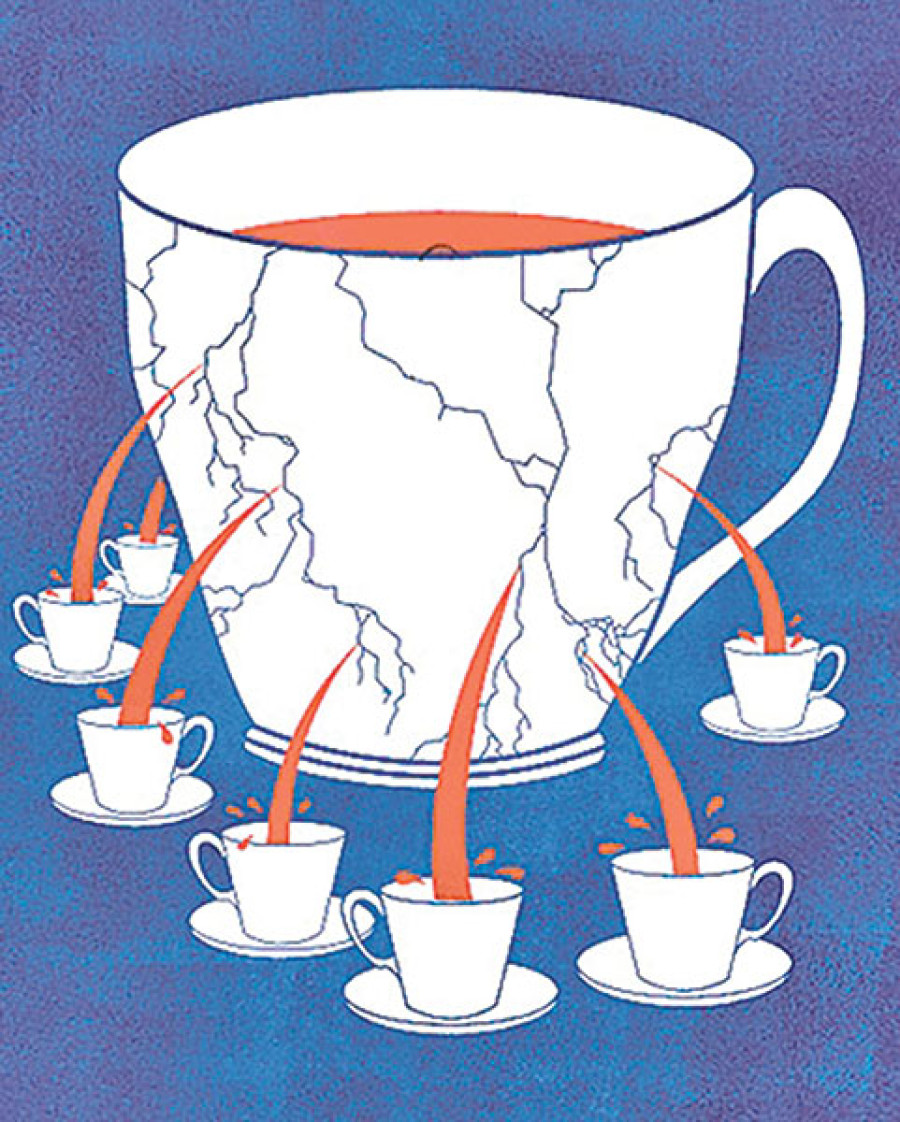

The long, hard road to federalism

A new report reveals the challenges that local governments are facing across the country

Shradha Ghale

The Democracy Resource Center Nepal (DRCN) has produced a timely and informative report on how federalism is being implemented at the local level. The report, titled ‘Functioning of Local Governments in Nepal: Preliminary Findings’, captures the multi-layered challenges that the newly formed local governments are facing across the country.

The findings reveal the numerous technical and administrative problems of local units; the uncertainty and confusion about various aspects of governance; the lack of training and resources; and conflicts arising from opposing interests, unclear hierarchies and overlapping jurisdictions. Disputes over names, centres and boundaries of local units, which had been silenced during the elections, have now resurfaced.

Centralised mindset

There is an enduring tendency to centralise power in Kathmandu. While everyone knows federalism essentially means devolving power away from the centre, the report shows how difficult it is to put this idea into practice. Many local representatives have complained about the central government’s attempts to continue its domination over local affairs. The centre has been sending “dummy laws” and directives to local units without taking the local needs into account. In some areas, local level bureaucrats have invoked the authority of the centre to bypass local elected representatives. In other instances, central level party leaders have manipulated the boundaries of local units to serve their own interests. Dhulikhel municipality even filed a complaint in the Supreme Court saying that the templates sent by the centre violate the principle of federalism.

Yet at the same time the local governments are seeking guidance and support from the centre. Many local representatives have emphasised they need training and more staff and resources rather than top-down instructions. So how can the centre provide support and guidance without eroding the autonomy of local government? This seems to be one of the big challenges in implementing federalism in Nepal. It is going to be hard to overcome the long legacy of centralisation, to move away from the structures and ways of thinking established over past decades. But unless those in power can break away from the centralised mindset, it won’t be possible to uphold the spirit of federalism.

Erasure of identity

Another challenge that is evident in the report is related to inclusion of marginalised groups and women. As many of us know, the kind of federalism Nepal finally got is very different from what marginalised groups had envisioned in the aftermath of the 2006 people’s movement. Back then they had demanded provinces based on identity. Now, forget getting an identity-based province, they are struggling even to keep their small clusters within the local units intact. This despite the fact that the technical committees are supposed to retain ethnic clusters wherever possible. One example provided in the report is of the Rajbanshi, an indigenous minority community in Jhapa. Although the Rajbanshi lobbied for a Rajbanshi cluster, they have been split into many wards and local units, which has vastly diminished their ability to organise and make collective demands.

DRCN’s finding on the Rajbanshi cluster is consistent with a broader trend. In 2016 various Janajati groups from across the country had complained to the Local Bodies Restructuring Commission saying their ethnic clusters had been divided into different local units. In Rasuwa, for example, Haku is one of the poorest VDCs with an almost entirely Tamang population. Seven of its nine wards were placed in one municipality, whereas wards 8 and 9 were merged with Uttar Gaya rural municipality, which has a mixed population. According to the ward chair of Haku, influential people from Uttar Gaya rural municipality wanted the two wards of Haku in their municipality because the 216 MW Upper Trishuli-1 hydropower project is located in these wards. The Tamang of Haku weren’t even allowed to give their municipality a Tamang name. Their new municipality was named Parvati Kunda. After continued pressure from the locals, the name has now been changed to Aama Chhodingmo, but it’s not clear which of the two names will prevail.

These examples show how much the marginalised groups have had to concede over the last decade. People who were demanding identity-based provinces at the start of the peace process are now begging to retain their tiny clusters. They had wanted province names that reflected their collective identity; now they aren’t even allowed to choose a name for their local unit.

Quotas not enough

The report doesn’t offer a rosy picture of the situation of women and Dalit local representatives. While the local government quotas for women and Dalits are certainly a positive development, it’s clear that quotas alone cannot guarantee their meaningful participation. Women representatives face numerous obstacles that are rooted in systemic discrimination and the deeply entrenched patriarchy. Many women deputy mayors and ward members are having a tough time carrying out their responsibilities, not only because they lack training and exposure but because people just aren’t willing to acknowledge them as figures of authority. Their male colleagues undermine them, try to micromanage their work and make decisions without consulting them.

Dalit women representatives continue to face untouchability and caste discrimination even as office bearers. The report mentions how Dalit ward members in Dhanusha and Parsa were asked to sit on the floor during assembly meetings. In fact several incidents of violence against Dalit women representatives have been reported in the media over the past year. The backlash has come from both inside and outside their homes. Last year Bina Mijar of Dhading who had stood for the ward member position committed suicide; many claimed she had been receiving death threats since she filed her candidacy. Again in July last year, Bayaansari Kami, a newly elected ward member of Rukum, was killed by her husband, who had apparently opposed her decision to stand for elections. Recently Mana Sarki, a ward member from Naraharinath rural municipality in Kalikot, was beaten to death by three high-caste women in her village. And these are just some of the reported incidents.

The experiences of women and Dalit representatives show that quotas are necessary, but they are only a small initial step towards addressing the history of exclusion in Nepal. Dominant groups need not fear that reservations will change the power equation overnight and strip them of their firmly established privileges. There are too many odds stacked against people from marginalised groups even after they reach decision-making levels. In addition to quotas, there must be institutional safeguards to protect them and ensure that they are fully able to perform their roles.

The report also seems to confirm many of our fears that it’s going to be harder to address systemic exclusion in the coming days. The government’s slogan of “development and prosperity” has overshadowed this agenda. This new narrative—that large infrastructure development is going to solve Nepal’s problems—is also being promoted at the local level. Every other municipality is now focused on building roads. What about other essential services that most people are still deprived of—namely, food, housing, education, health care and livelihood? Shouldn’t local governments be paying equal if not more attention to such needs? And what is going to happen to people who will lose—or have lost— their homes, lands, forests and livelihoods to these mega projects? The drumbeat of ‘bikas and sambriddi’ seems to have drowned out such questions.

Ghale is a freelance writer

9.51°C Kathmandu

9.51°C Kathmandu