Opinion

To err is inhuman

Surgical teams should adhere to checklists before, during and after procedures to prevent medical errors

Dr Gopal Sedain

It was planned for Rita to have brain surgery. She was taken into the operation theatre and brought out after a few hours. When she woke up, she was surprised to know that the operating surgeon had operated on the right side of her brain instead of the left side where she had a tumour. The family was devastated and so was the surgeon. This is a hypothetical situation, but who should be blamed in the event of such a mishap?

These ‘wrong-site, wrong-procedure, wrong-patient errors’ (WSPEs) are rightly termed ‘never’ events—errors that should never occur and that indicate serious underlying safety problems if they do. Most often, it is the clinician who should be blamed for such errors. Being the captain of the ship, the onus is definitely on the leader. However, we should develop systems and cross checks so each step and staff involved will be vigilant. WSPEs can be a devastating experience for the patient and families and have a negative impact on the surgical team. WSPEs most commonly occur in orthopaedic, general surgery, urological and neurosurgical procedures.

Fatal errors

A landmark report released in 1999 by the Institute of Medicine (US) entitled To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System concluded that more Americans were dying annually from medical errors than motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer and HIV. This report spurred a call to action to the healthcare community to improve patient safety.

Different factors may contribute to this problem. Care provider factors, procedure factors or patient related factors are some of them. Heavy work load, surgeon fatigue, multiple team members, environment and lack of accountability may play a role in increasing errors. The attitude of surgeons that they can make no mistakes may too add to the errors. Procedure related factors like not marking or checking the marked site, not cross checking the records, doing the procedure in a new room, doing similar procedures back-to-back and doing surgery in a prone position—when patients lie on their chest and not their back—can contribute to the problem. Regarding patient related factors, a patient may be mistaken for another with the same name, or the patient may not have been properly communicated to before the procedure.

Preventing further mishaps

WSPEs are generally caused by lack of a formal system to verify the site of the surgery or a breakdown of the system that verifies the correct site. By using root-cause analysis, a process that determines the underlying organisational causes or factors that contributed to an event, the Joint Commission in the US found the top root-causes of WSPEs to be communication failure (70 percent), procedural noncompliance (64 percent) and leadership (46 percent). More WSPEs were seen in emergency cases, where multiple surgeons were involved, where multiple procedures were involved, and where there was time pressure, unusual equipment or setup of the room had been changed.

Early efforts to prevent WSPEs focused on developing redundant mechanisms for identifying the correct site, procedure and patient, such as ‘sign your site’ initiatives that instructed surgeons to mark the operative site in an unambiguous fashion. This strategy is a must, and I strongly recommend that even patients and family demand this from the hospital staff. However, it soon became clear that even this seemingly simple intervention was problematic. An analysis of the UK’s efforts to prevent WSPEs found that, although dissemination of a site-marking protocol did increase use of preoperative site marking, implementation and adherence to the protocol differed significantly across surgical specialties and hospitals.

The Universal Protocol for WSPEs is based on prevention theories that drive safety practices in high-risk industries. The operating room is complex with ‘tight coupling’ of processes that happen very quickly and cannot be turned off once started, and where failed parts cannot be isolated from other parts, resulting in an unsafe process. According to a study, 62 percent of WSPE cases can be prevented if providers (surgeons, including nurses, anaesthesiologists and other staff) adhere to the Universal Protocol. In this study, the authors concluded that the Universal Protocol would not have prevented the remaining one-third of WSPE documented cases because of errors initiated in the weeks before surgery (for example, wrong documentation and inaccurate labelling of radiological reports).

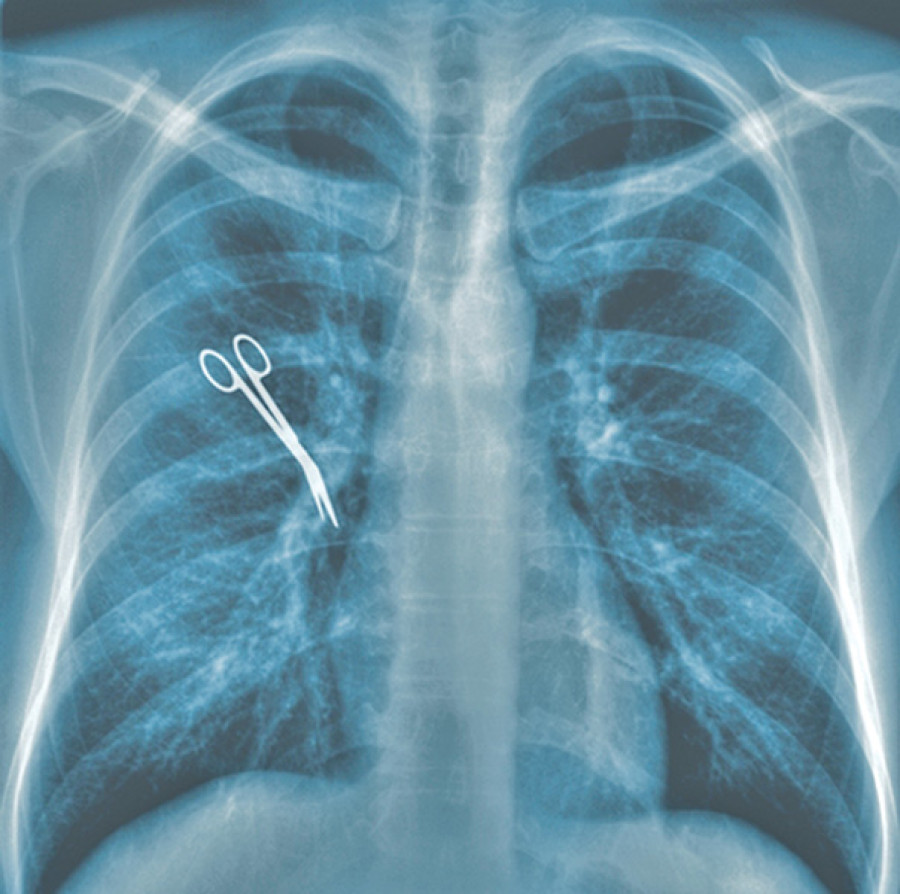

There should be adherence to the Universal Protocol by using the World Health Organisation checklist before, during and after surgery. This not only decreases chances of wrong site, procedure and patient, but also decreases chances of unintentionally leaving foreign bodies and encourages each member of the operating team to be vigilant. Many centres in Nepal have been using the protocol and checklist. However, strict implementation by the administration and legislative bodies cannot be overemphasised. The universal right of patients to have right-patient, right-site and right-procedure should always be the goal of the treating team.

Sedain is an assistant professor of neurosurgery at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu