Opinion

The BRI trap

Historically, Indian public opinion towards China has invariably remained one of distrust and paranoia.

Achyut Wagle

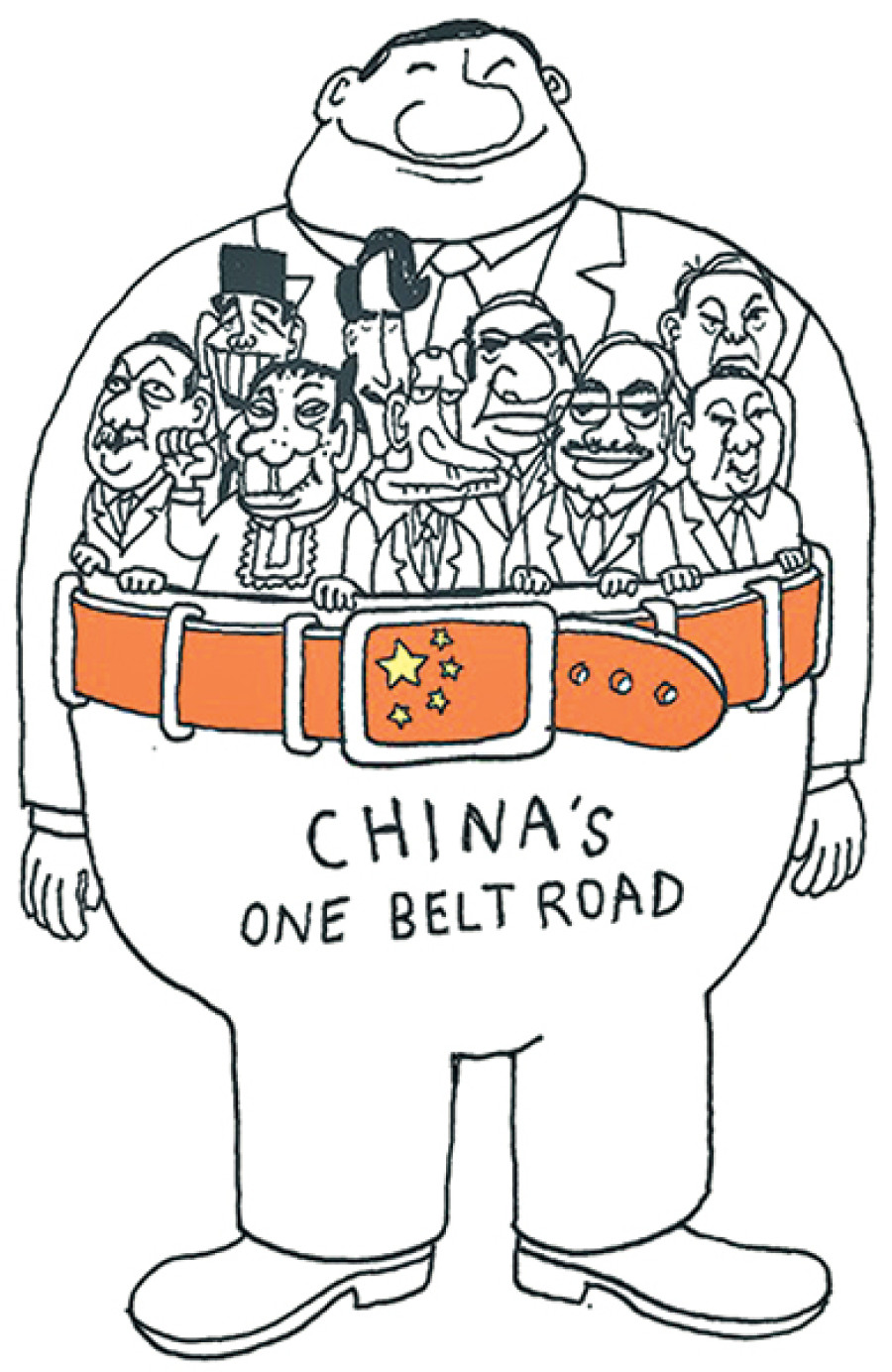

Historically, Indian public opinion towards China has invariably remained one of distrust and paranoia. But now, perhaps for the first time in history, it is starkly divided on how India should view and interact with the ‘new’ China, thanks to the aggressive Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), also known as the One Belt One Road (OBOR) project. Interestingly, the ‘road’ is not actually a road, but a 21st century maritime silk route linking China’s southern coast to the Mediterranean, east Africa and southern Europe. The ‘belt’ is meant to revive the old ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ in addition to proposed ‘noodles’ of roads that would connect China with west Asia, Europe and Africa, via Central Asia.

In essence, India boycotted the OBOR summit held in Beijing in mid-May in which 29 heads of state or government from different parts of the world participated. Except for Bhutan, all of India’s neighbours sent high-level delegations to the summit. India could derive solace only from the fact that German chancellor Angela Merkel and US president Donald Trump turned down the Chinese invitation to the summit.

Three Indian views

There are three distinct strands of opinions that Indian intelligentsia is now espousing. First, India did the right thing by avoiding participation in the summit, given that China is investing about $50 billion in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a highway project that runs through the Gilgit-Baltistan region in Jammu and Kashmir over which India claims sovereignty. Defenders of this ‘boycott line’ argue that India’s participation would have been construed as its surrender to Pakistan’s claim over that particular territory.

The second strand of thought maintains that India should have actively engaged in positive diplomacy and used the summit as a forum to voice its concerns and differences. This school of thought holds that it was undiplomatic to boycott the conference and miss the opportunity to express the Indian viewpoint on the entire project.

The third argument is in favour of involvement, meaningful participation and harnessing of benefits that the BRI would hopefully generate. This school of thought urges to take the economic might of fast emerging China as well as its proximity to India into consideration while operationalising the latter’s economic diplomacy. Chinese President Xi Jinping has promised to invest $900 billion in the next five years, mainly for infrastructure development on both the ‘belt’ and ‘road’ fronts. Clearly, China appears determined to employ this ambitious project not only to expand its pure mercantilism but also to exert its geo-strategic and geo-political muscles simultaneously. As such, it is natural for India to be apprehensive of losing its traditional sphere of influence as these two giants share the same neighbourhood with a bead of smaller nations between them.

Deepest trap

India is visibly perturbed by these recent developments, but it has very limited options to match China’s resources, finesse and assertiveness. India is gradually falling into the Chinese trap, largely by default. First, China is India’s largest trade partner, with which it has a bewilderingly unfavourable balance of trade. Indian trade deficit with China in the fiscal year 2016-17 was about $51.1 billion. India could export only $10.1 billion worth of goods as against its imports worth $61.2 billion. The deficit is $3 billion higher than in the previous fiscal year, and the exports have dwindled. Indian exports are of high volume, low value nature such as granite, copper ores, cotton, cotton yarn etc, while Chinese imports are mainly high value electronics, machinery and fashion products.

Second, India unfortunately has very little capacity to alter this trade scenario in the immediate future. As a barely $2.5 trillion dollar (in nominal terms) economy, India simply cannot compete with the pork-barrel spending fuelled by the Chinese economy of $12 trillion. The Chinese promises of investment and financial support to countries ‘in need’ are so huge that no country, let alone India, in the world will now dare to compete with China. Indian elites and commoners alike take great pleasure in asking their weaker neighbours why they have fallen into the Chinese trap. They fail to realise that the trap India has fallen into is the deepest among all.

Third, India is not using the soft-power advantage it has in order to retain its traditional influence in the region. By using this advantage, India could help contain China. Democracy is one of the most effective soft powers that India possesses as the world’s largest functional democracy; it could extend this power to its neighbourhood in good faith. Linguistic and cultural homogeneity with prominent neighbours within the region could have served as another key advantage. Ease of access at the sub-continental level is the third component India could have taken advantage of. But the Indian policy-making class doesn’t seem to see any of these realities, which, in turn, has helped China to literally encircle India.

Should Nepal bother?

Nepal has signed the OBOR framework agreement and participated in the OBOR summit. But these symbolic developments alone are unlikely to practically alter Nepal’s geo-economic reality of an India-dependent economy. At best, the BRI framework might provide some form of transport connectivity in the long run. But unless Nepal has something substantial to sell to China (or India) by using that

connectivity, any such access will only benefit the other party, and our economic dependence will only deepen. But in Nepal, the BRI has become a very interesting tool for ultra-nationalist adventurism.

In the recent local polls, the CPN-UML registered an emphatic victory. Needless to say, the UML is now an openly pro-BRI party and fought elections on an anti-Indian nationalistic plank. If the local poll results are any indication of the outcome of provincial and general elections due by January 21, 2018, the UML is poised to exploit its ‘pro-nationalist’ image in the upcoming polls as well.

Ironically though, the UML’s increased political space is a gift of the Indian foreign policy faux pas. An absolutely needless, five-month-long economic blockade imposed on Nepal by India a year ago pushed neutral voters towards the UML which advocated increased engagement with China; the government led by the UML had vowed to be part of the BRI. Regardless of whether Nepal will benefit from the BRI, it was compelled to be a part of it due to public pressure.

Even after all this, India isn’t forthcoming in correcting past mistakes, say, on its Nepal policy. The BRI-trap is bound to tighten around India. Nepal is already trapped between China and India.

Wagle, a founding editor of the economic daily Arthik Abhiyan, is an eco-political analyst

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu