Opinion

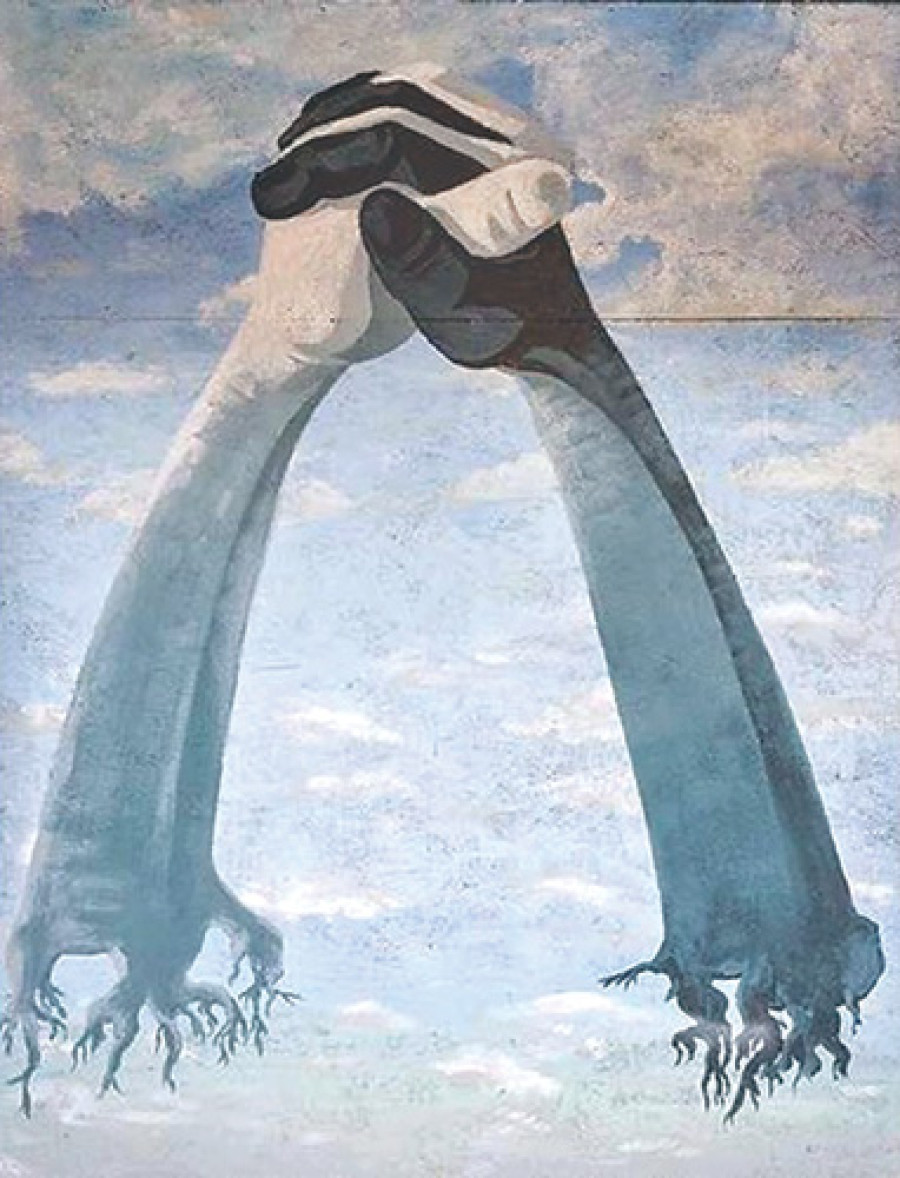

Human versus national security

What comes first, human or national security? This has been an enlivening, yet a never-ending debate. In the case of national security, threats are only variants of orthodox-external dimensions.

Mahendra P Lama

What comes first, human or national security? This has been an enlivening, yet a never-ending debate. In the case of national security, threats are only variants of orthodox-external dimensions. These are mostly determined by the threat to a nation’s sovereignty, which in turn is largely based on the integrity of its geographic whole. The state has been a referent and determining object in national security; it is seen as an impregnable fortress. Therefore, national security has become a sensitive issue. It overwhelms and marginalises the rationale for all other critical, human-centric securities, including food, environment and energy. In fact, sensitivity in the interpretation of national security is often used to justify a number of things, including actions that bring conflict, violence, dislocation and underdevelopment.

Advocates of human security vehemently confront the orthodox account of security. They question its adequacy in understanding and assessing the actual nature and scale of threats to human beings. In the perspective of human security, human beings, not the state, are the primary referents. This constant debate has become all the more pertinent in the current context, given the end of the Cold War and the changing nature of threats and instability among the human populace.

Domestic and international politics

Advocates highlight the complexity of identifying sources of insecurity affecting humans in various situations and locations. They deal with crucial queries like ‘what makes people feel secure?’ The basics of human security are primarily ensured by meeting common aspirations most valued by people. These include food, adequate shelter, good health, education for children, protection from violence, freedom from pervasive threats to basic rights and from other fears. They argue that these non-traditional security parameters determine foremost the state of human security, followed by the determination of national security. However, in this situation, the state-society relationship is separated from ‘international relations’. Thus, human security is perceived exclusively in terms of the domestic political realm.

South Asia has been a theatre of major security concerns and vulnerabilities at various levels. The nature and contents of these insecurities are diverse and mostly relate to non-traditional paradigms. They range from political demands pursued via terrorism and insurgency, forced and voluntary migration resulting from socio-political conflicts, and environmental displacement caused by natural disasters. Such poor states of human security are directly related to livelihood and nutrition concerns, decreasing accessibility to public utilities, human rights violations, skewed distribution of natural resources, harmful development and technological interventions, natural disasters, inimical production structures and market based reforms. None of these are recognised in the orthodox framework of security.

Changing traditional contours

South Asian strategic thinkers constantly sideline attempts to bring the human security discourse to the forefront and thus change the traditional contours of security. This is attributed to the very nature of post-colonial state formation, strategic and military alliances, and diplomatic engagements. National security issues were oriented towards external parameters, while internal dynamics were largely ignored. Thus, in the interest of larger military security, the insecurity felt by citizens has often been neglected. Human security as an internal agenda and military security as a national agenda are subject to two distinct treatments by the same state.

Since these ‘other threats’ to security do not directly impinge upon sovereignty, they are generally addressed in the exclusive framework of nation-building, socio-political contingencies and development dynamics. They are consciously kept out of the national security agenda.

For instance, despite death from hunger-related causes, suicide by farmers and conflict triggered by deprivation, the issue of food security and the protection of sovereignty have never been linked. This leads to a fundamental question: For whose security are the national borders to be protected? Where does individual and national security overlap?

However, there have been conscious attempts by scholars, institutions, civil society entities and government agencies to ‘import’ the emerging international discourse and link it to the changing contours of security in the complex realities of South Asia. Overarching matrices of security are fast changing. The notion of nationalism based on perspectives of territoriality is diminishing. Security has assumed wider connotations that go beyond borders. An understanding of the situation at the local and micro level, and multi-faceted border interactions are becoming vital. Security dimensions are becoming increasingly local.

Demystifying linkages

In some situations, human insecurities have resulted in protracted violence, insurgencies and terrorism, thus attracting crossborder sympathies and affiliations. This in turn has created threats to both ‘internal’ and ‘national’ security. This tendency was documented in a number of cases by the Kuki-Naga clashes in Manipur, the Khalistan movement of the 1980s, and the LTTE and army clashes in the north-east provinces of Sri Lanka that ended in 2009. In India, over 160 districts in 13 states have been affected by Naxalite influence and violence, making it the “single biggest internal security challenge”. This also shows that under particular situations of human insecurity, “our own people” can become a threat to both internal and national security. However, even in this context, the dimension of human security is still considered separate from the national security of a state.

Another example of this separation is demonstrated by the differing classifications of the communal riots of Gujarat in 2002 and the Kargil war that India fought against the Pakistani forces in 1999. Both of these conflicts resulted in the death and displacement of a large number of people, destroyed property and caused huge financial losses. The central security forces—including the Indian army—were deployed in both situations. Both had the potential to conflagrate into major national security crises. Both were covered extensively by the media and widely discussed in the Indian parliament. In fact, the former nearly cost the stability of the then National Democratic Alliance government. Both created serious human insecurity. Yet the treatment by the Indian state was distinctly different and discriminatory.

Despite these striking similarities, the conflict in Gujarat remained an internal security concern that was dubbed a law and order problem, whereas the Kargil war was classified as a national security issue for India. Were they classified as such because the first essentially took place within India and the second had a major external dimension? Or was it because the first was more localised and the second had national appeal? In fact, both were localised problems with the potential to spread further and cause widespread conflagration. Both had strong national appeal. Despite high levels of human insecurity in the Kargil war, such insecurity was overshadowed by national security concerns. Perhaps states are reluctant to classify internal human security problems as national security problems due to reasons of political denial and risks to power.

Similarly, why are cases of extreme left violence and conflict such as the Maoist movement classified as internal law and order problems and regarded as non-traditional threats, while the insurgency in north-east India (Nagaland and Manipur) falls in the ambit of national security as a traditional threat? What prevents the recognition of cases such as the Maoist movement as national security threats? What is the difference between ‘internal’ and ‘national’ here? Both cases have elements of convergence, yet in the thinking of states, they hardly have a point of convergence. What makes these two concepts deviate? Are there any substantive factors that keep these two concepts mutually exclusive and tightly compartmentalised? Or is it only a perceptual difference based on a prevalent mindset? The answer to these questions could also provide a solution to complex issues concerning orthodox versus non-orthodox paradoxes of security. Perhaps this could end the monopoly that nation-oriented, orthodox security thinking has over the human security discourse.

Lama, a former member of National Security Advisory Board of the Government of India, is presently a high end expert in the Institute of South Asian Studies, Sichuan University, China

23.73°C Kathmandu

23.73°C Kathmandu