Opinion

Aid in pre-1990 Nepal

India and China launched their aid programmes in Nepal in the 1950s. Both have actively contributed to the building of physical infrastructure in the form of roads, bridges and hydro-electricity.

Mahendra P Lama

India and China launched their aid programmes in Nepal in the 1950s. Both have actively contributed to the building of physical infrastructure in the form of roads, bridges and hydro-electricity. Till at least 1990, over 84 percent of Indian and 65 percent of Chinese total assistance was targeted towards the construction of roads, irrigation plants, airports, power and water supply systems.

This sectoral concentration of assistance broadly matched Nepal’s priority to focus on the development of transportation and communication structures during the first four five-year plans (1956-57 to 1970-75). After the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict, Peking started to emphasise the building of roads; however, fundamental differences emerged in other sectors. Over the years, India has had a hand in almost all possible areas of cooperation including agriculture, education, technical exchange, horticulture, sports and veterinary services. China, on the other hand, strictly limited its assistance to roads, power, industry and some social projects. It refrained from participating in sectors like agriculture, rural development and communication. Nepali ruling elites were of the view that while the Chinese might bring along new agricultural techniques, they could also bring along their agricultural ideology and institutions. In contrast, Indian agro-economic institutions were considered congenial to Nepal.

In the industrial sector, China established full-fledged industries focusing on the production of textiles, bricks and tiles, leather, cement, paper and sugar. They generally undertook relatively smaller industrial ventures. Given the limited gestation period of these projects, there was a swift yield of tangible results. These factories produced mass consumption goods that could rival Chinese exports. This import substitutive character of industrial cooperation reduced China’s trade with Nepal. This reduction was perceived as being the main motive behind the northern neighbour’s promotion of this sector.

In contrast, Indian aid participation limited itself to building industrial estates consisting of numerous smaller sheds which had no substantial independent production capacity. This created doubt over the genuineness of India’s interest in industrialising Nepal. Private Indian investors entered the industrial sectors in a wider way through investment in diverse areas.

India’s contribution in the area of irrigation has been substantial. With projects like Kosi (1969/1986) and Gandak (1984), India has helped Nepal make strides in rural electrification. China’s contributions, however, were limited to a project at Pokhara (1985). The total number, size and capacity of Indian projects outnumbered Chinese projects.

Project location

An important indicator of Indian and Chinese aid motives in Nepal has been the location of their projects. Though exclusive zones were not defined, Indian projects were mostly located either in southern Nepal or in and around Kathmandu. India’s major projects such as the Gandak and Kosi multi-purpose river projects, East-West Highway and Tribhuvan Highway either originate from the southern areas contiguous to the Indian border, or are located in these areas. These projects establish a direct connection between India and Kathmandu.

Tribhuvan Highway is conceived as having tremendous strategic importance. Built in 1956, this was the first national highway of Nepal, and formed a link between Bhainsi (at the Indian border) and Thankot (near Kathmandu). India has denied the allegation that strategic interest is the motivation behind this project, stating that the highway in fact helps Nepali defensive forces. Nepal was amenable to this project given that it would boost accessibility to trouble-prone areas via easy mobilisation of security forces to strengthen internal security. This highway enabled the establishment of development projects in various areas that would otherwise be unreachable, requiring immense resources beyond Nepal’s capacity.

Strategic dimensions

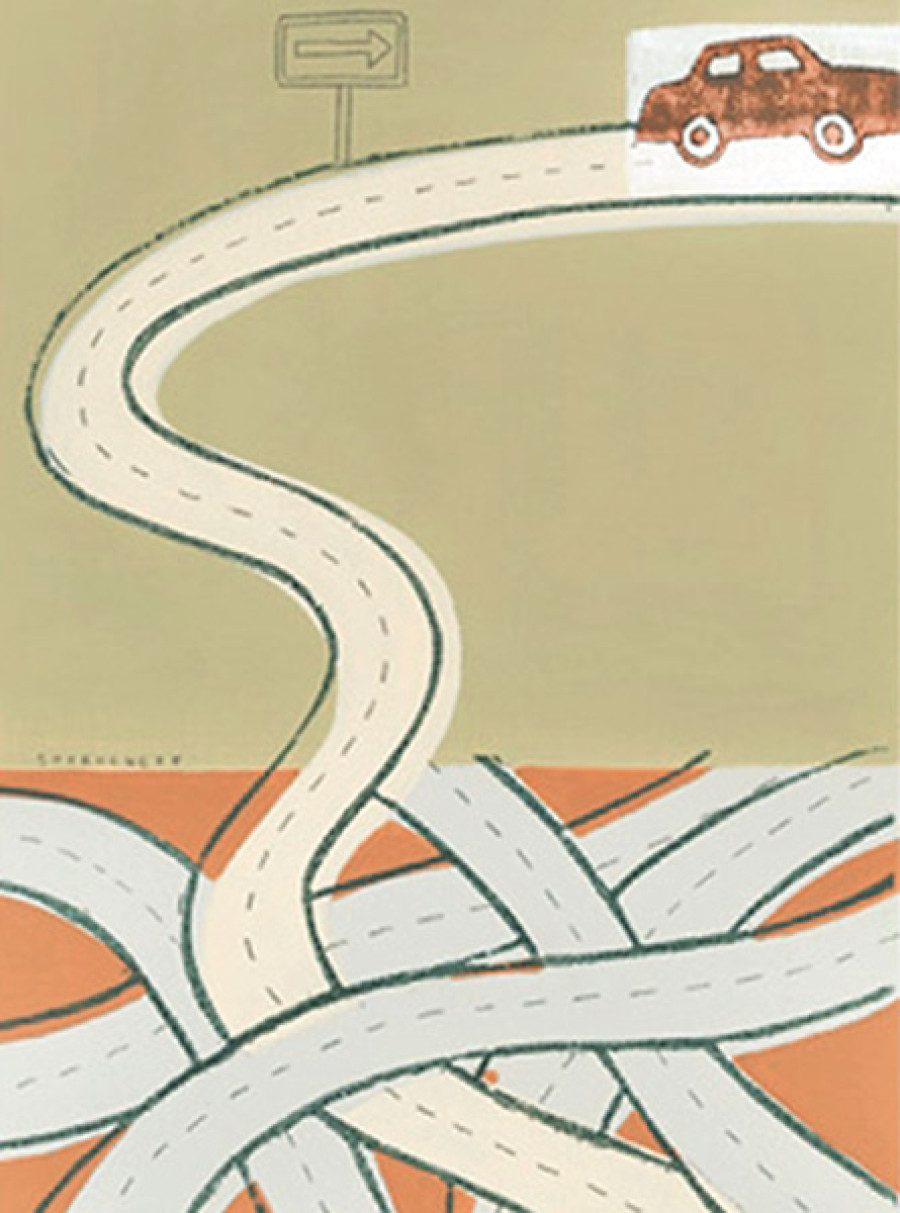

Indian roads including Tribhuvan Highway and Pokhara-Sunaoli (Siddhartha) Highway have been built over difficult terrain. Primary engineering to build these roads focused on constant ascending and descending to lose and gain height, resulting in a lot of turnings and zig-zags. These roads had to be well-built given the topographically contrasting areas they ran through.

India’s main aim behind establishing the planned routes was to gain access to the economically important Palung valley. Though India inherited some of the best known road building techniques, skills and institutions from the British India, it did not utilise this technology and skill while constructing highways in Nepal. These were constructed by defence personnel.

Nepali strategic analysts hold the view that the army forces enlisted for constructing the highway were instructed to touch certain strategic points of importance, such as Palung, Daman and Thankot. Tribhuvan Highway remained a lifeline for Nepal till the construction of the Narayangarh-Gorkha highway in 1981.

In the same way, the Chinese projects are found either in northern Nepal, or in and around Kathmandu. Despite expressions of interest to undertake projects in the southern belt near the Nepal-India border, the Nepali government managed to confine the Chinese to the north for many years. However, in the 1980s, the Chinese made their presence felt in the Tarai via projects like the Lumbini sugar mill. The Arniko Rajmarg (Kathmandu-Kodari Highway) directly connected Kathmandu with the Chinese border.

Riverine designs

Unlike Indian road projects, the Chinese ones were built mainly on river banks. The Arniko Rajmarg was completed in 1967 and mostly follows the smooth natural slopes of river basins like Rosi Khola, Jhiku Khola, Sunkosi and Bhotekosi despite topographically challenging terrains. Similarly, its other major road project, the Kathmandu-Pokhara (Prithvi Highway) constructed in 1973 also follows the banks of the rivers such as Seti, Marsyandi and Trishuli.

The Chinese regard this trend of building along river banks as a road construction technique to enable easier transportation. Unlike roads built by India, this technique of road construction resulted in very few sharp U turns and steep ascents. Though Chinese technicians and engineers never disclosed the reason behind this pattern of river bank road building, Nepali engineers have discerned that it provides the shortest possible routes through slopes that allow for easy drives to reach particular destinations. Additionally, raw material required for road construction such as stones, sand, gravel and water are easily available by the river banks. Road access made the construction of water resource projects such as the China-built Sunkosi hydel project much easier. Engineers have also opined that the difficult areas these roads run through make aerial military attacks targeting the destruction of the roads strategically ineffective.

Nepali engineers are of the opinion that the maintenance of such roads that run along river banks is challenging, costly, and presents serious operational constraints. Not to mention disasters such as earthquakes, and even the normal monsoon deluge in rivers affects fragile stretches of road. Since most of the drainage coming to rivers must cross this road, construction becomes expensive. Some of the alignments are so close to rivers that even the slightest flash flood could wash out huge portions. This was the situation from 1950 to 1990. The story is different now.

Lama teaches at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and is presently a high end expert in the Institute of South Asian Studies, Sichuan University, China

8.85°C Kathmandu

8.85°C Kathmandu