Opinion

Nakarmi, who designed ground breaking water mills, dies at 71

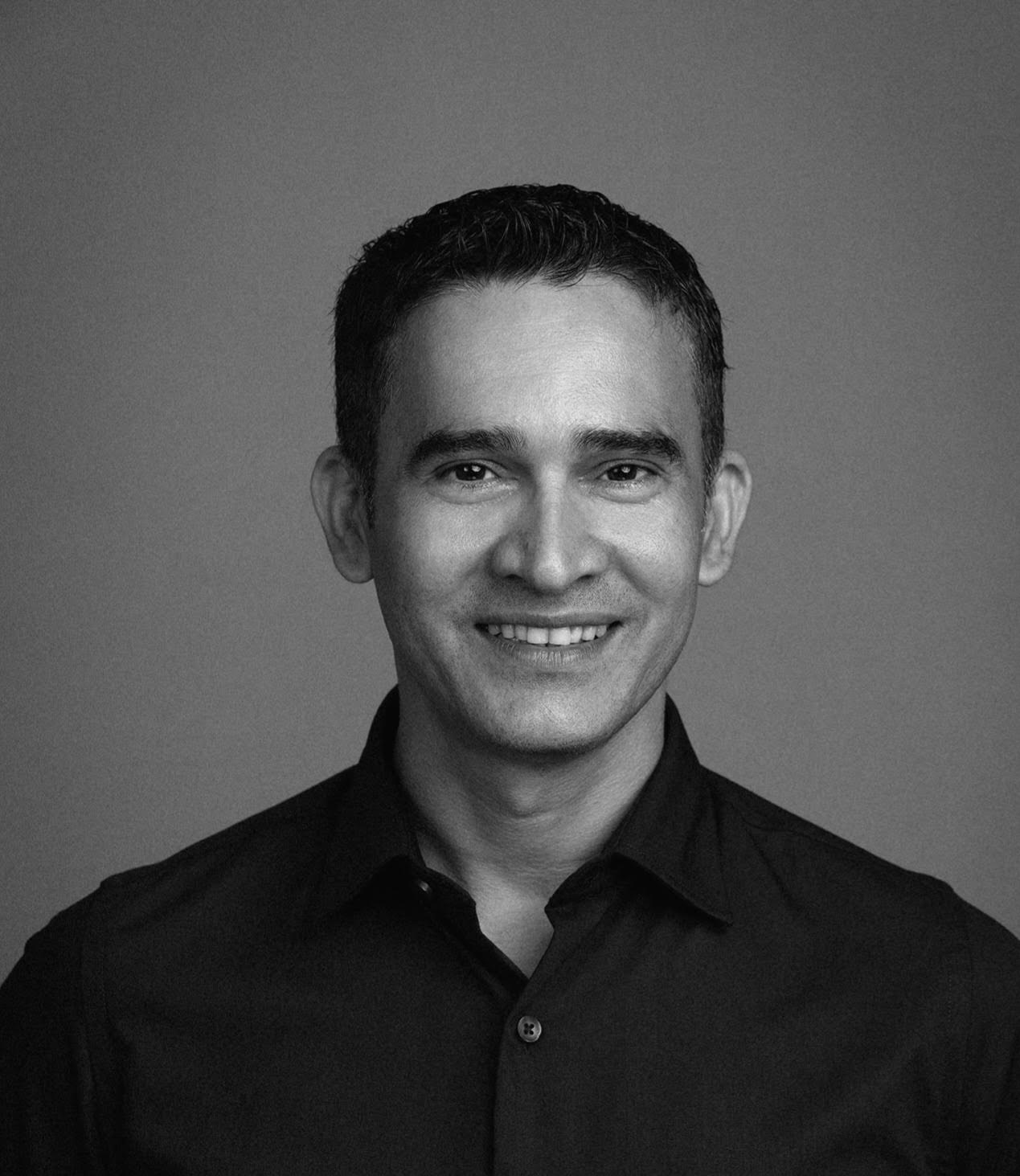

Not known to many outside the renewable energy fraternity, Akkal Man Nakarmi was a prominent innovator in conserving, protecting, and modernising traditional water harvesting technologies and the most influential individual contributor to micro-hydro development in Nepal.

Bibek Raj Kandel

Not known to many outside the renewable energy fraternity, Akkal Man Nakarmi was a prominent innovator in conserving, protecting, and modernising traditional water harvesting technologies and the most influential individual contributor to micro-hydro development in Nepal. Mr Nakarmi passed away earlier this month at the age of 71. People who knew him in the renewable energy circle have posted messages of condolence in remembrance of his services to the sector. It was his design of the Multi-Purpose Power Unit (MPPU) that improved on traditional Pani Ghattas; with the use of metal buckets, a metal shaft, and a pipe in place of the chute, his innovation tripled the output efficiency of traditional ghattas. This was the first major upgrade for this ubiquitous grain grinding technology, also known as the Norse Wheel, which spread from West Asia to Southeast Asia starting around the seventh century BC.

Mr Nakarmi was an extraordinary individual who paved the way for innovations in the design and application of water turbines in Nepal. He was also pivotal in preserving and upgrading traditional technology practices that carry value and wisdom passed down from generation to generation. With the skills and wisdom inherited from his forefathers, Mr Nakarmi linked his classical modern education with indigenous knowledge—both of which played an equal part in his work and success. Today, thousands of Improved Water Mills and micro-hydro power plants are a result of the lifelong work of Mr Nakarmi.

Modernising what was traditional

In March 2012, I was writing a conference paper on the role of traditional knowledge systems on climate mitigation in Nepal. It occurred to me that having a personal conversation with Mr Nakarmi on the evolution of traditional water mills would be helpful. One of my friends gave me his contact details. I dialed his office number but it was his son, Tirtha Man Nakarmi, who picked up the phone. He runs Kathmandu Metal Industries that his father established. I asked if he could connect me to his father. He agreed to arrange a meeting at his residence. However, upon arrival I was told that the older Mr Nakarmi was bedridden with severe back pains and could not meet me. I didn’t insist on meeting him. Instead, his son volunteered to answer my questions.

Arguably, the first attempt to radically innovate and enhance traditional technology practices in Nepal was made by Akkal Man’s father Gopal Man Nakarmi, who designed the first metal water bucket wheel in Nepal in the early 1940s. Like father, like son. With a Swiss engineer, Andreas Bachmann, Akkal Man explored ways to upgrade traditional ghattas by varying heads and flows. That is when he successfully designed a low-cost multi-purpose power unit in 1967. Together with Surendra Mathema, Akkal Man also developed the Peltric set—a compact electricity-generating unit made by fitting a small diameter Pelton Turbine runner on the shaft of an induction generator. A prolific inventor with tremendous ingenuity, Akkal Man made scores of innovations to the cross-flow turbine and small propeller turbines. The 50 years he committed to his work is also a testimony of his concerted efforts to safeguard and modernise intrinsic traditional technologies that were the culmination of centuries of practices and experiences.

Easy technology, hidden dangers

The history of diesel operated agro-processing mills in Nepal is not more than 70 years old. It was only introduced after 1956 when Nepal’s first highway—Tribhuvan Rajmarg—was constructed. This highway gave the Tarai motorable access to Kathmandu, thereby instigating a new era of consumerism in Nepal. Consequently, the state assisted the proliferation of new diesel operated machines and systems in the 70s and 80s without investigating methods to modernise local resources and indigenous technology. This move caused many people to abandon traditional water mills and resulted in the exponential use of oil products by many (previously) self-reliant rural societies of Nepal. Today, it is remarkable that almost half of Nepal’s 25,000 ghattas have been upgraded to the Improved Water Mill using the MPPU design, enabling them to additionally drive rice hullers and oil mills, and generate electricity. This was a significant intervention to combat the proliferation of diesel mills in the rural hills.

Today, many traditional technologies and practices still run the risk of disappearing due to the use of modern technology that is more easily available and efficient. While the merits of modern science are undeniable, unchecked proliferation of western machines that give no regard to preserving and improving indigenous practice should be curbed. By doing so, the self-reliant and resilient nature of traditional rural societies of Nepal can be preserved to some degree. The disadvantages of these modern technologies were shown when our society had to return to basics for survival when all modern facilities became dysfunctional during the recent blockade. The prevalent method of bringing new western machines to Nepal—entailing a mere transfer of technology without weaving them into the fabrics of traditional society—is wrong. Akkal Man’s work was groundbreaking in the way he managed to intertwine modern science with traditional technology. Many will miss this prolific inventor.

Kandel is an energy expert; he appreciates the inputs of Mr Bikash Pandey, Director of Winrock International, Washington DC, to this article.

22.68°C Kathmandu

22.68°C Kathmandu