Opinion

Report at your own risk

Press freedom remains a myth in daily practice despite broad legislative measures

Bhanu Bhakta Acharya

Press freedom and freedom of expression in Nepal made little headway in 2016. Silencing critical news reports through assault, intimidation or threats was observed as the key strategy of government and non-government actors. No journalist was killed last year, but 19 of the 26 cases of death or disappearance during the Maoist conflict still have not entered the judicial process, according to Freedom Forum. The government has also tried to curtail press freedom guaranteed by the constitution. On June 14, it issued an Online Media Operations Directive under which online news portals can be shut down if they fail to register or renew the website annually, publish materials deemed to be illegal or immoral, or spread misinformation or reports lacking authoritative sources. These provisions contradict Article 19 (3) of the constitution that guarantees disruption-free media operation, except in accordance with the law.

Similarly, Press Council Nepal (PCN) had planned to conduct licensing exams for journalists, consisting of a written test, oral interview and practical assignment, as per the recommendations of the Journalism Ethics Qualification Test Taskforce. The move was criticised by media stakeholders who argued that state-run PCN was attempting to curtail freedom of expression and journalistic independence. In early May, immigration authorities deported a Canadian social media user Robert Penner after revoking his visa for his social media posts, which were mostly critical of the government. The authorities accused Penner of endangering Nepal’s social harmony and national unity.

Not so free

Himal Southasian, a quarterly not-for-profit journal published from Kathmandu, was shut down in November after 29 years of regular operation. The magazine said that government officials did not cooperate in releasing funds that had been donated for its publication. Magazine sources said that a critical report published in a sister publication Nepali Times about the abuse of authority by the chief of the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA) had led to the non-cooperation. Additionally, the CIAA filed a case against Kanak Mani Dixit, publisher and editor of Himal Southasian, charging him with financial irregularities. Dixit was held for 10 days in March and released following a Supreme Court order.

Similarly, the District Forest Office (DFO) demolished a building housing the studios of community broadcaster Radio Dhading inside Amarawati community forest. On September 24, the DFO bulldozed the building and damaged radio equipment for encroaching on forest land. The National Human Rights Commission condemned the act as an obstruction of freedom of expression.

The number of intolerant acts by various state and non-state actors increased in the past year. There were nearly two dozen incidents in which security personnel arrested and manhandled journalists, and damaged their equipment while they were gathering news. On April 10, the police assaulted Kabin Adhikari, a photojournalist at Onlinekhabar.com, when he was taking pictures of civil servants being arrested for protesting inside Singha Durbar, the government’s main administrative building.

Examples of harassment

Journalist Arjun Thapaliya, editor of Anukalpa daily published from Siraha district, was arrested on November 23 on the charge of committing a cyber crime, and held in police custody for nearly a week. According to a news source, Thapaliya had been detained for his critical reports about the unprofessional activities of the police administration in the district. Similarly, on December 2, the police abused Anil Tiwari, a reporter with Image Television, and destroyed his camera as he was covering women protesters being roughed up at the District Court in Parsa.

Meanwhile, non-state actors have been equally responsible for assaulting or harassing journalists for publishing critical news reports. On June 10, locals attacked Bhanu Niraula, a radio journalist in Solukhumbu district, over a news report. Two photojournalists, Saroj Baiju of Annapurna Post daily and Chhiring Lama of Commander Post daily, were attacked and their cameras damaged while reporting a protest by taxi drivers and entrepreneurs in Kathmandu on September 27. Krishna Thapa, a reporter at Kantipur daily in Nuwakot, received a death threat after publishing a news story on October 22 about the sale of unhygienic rice from a food store run by the president of the local Chamber of Commerce and Industry. In Siraha district, a hospital employee harassed Mithilesh Yadav, a reporter at Nagarik daily, on November 21 while he was reporting a dispute between patients and the hospital.

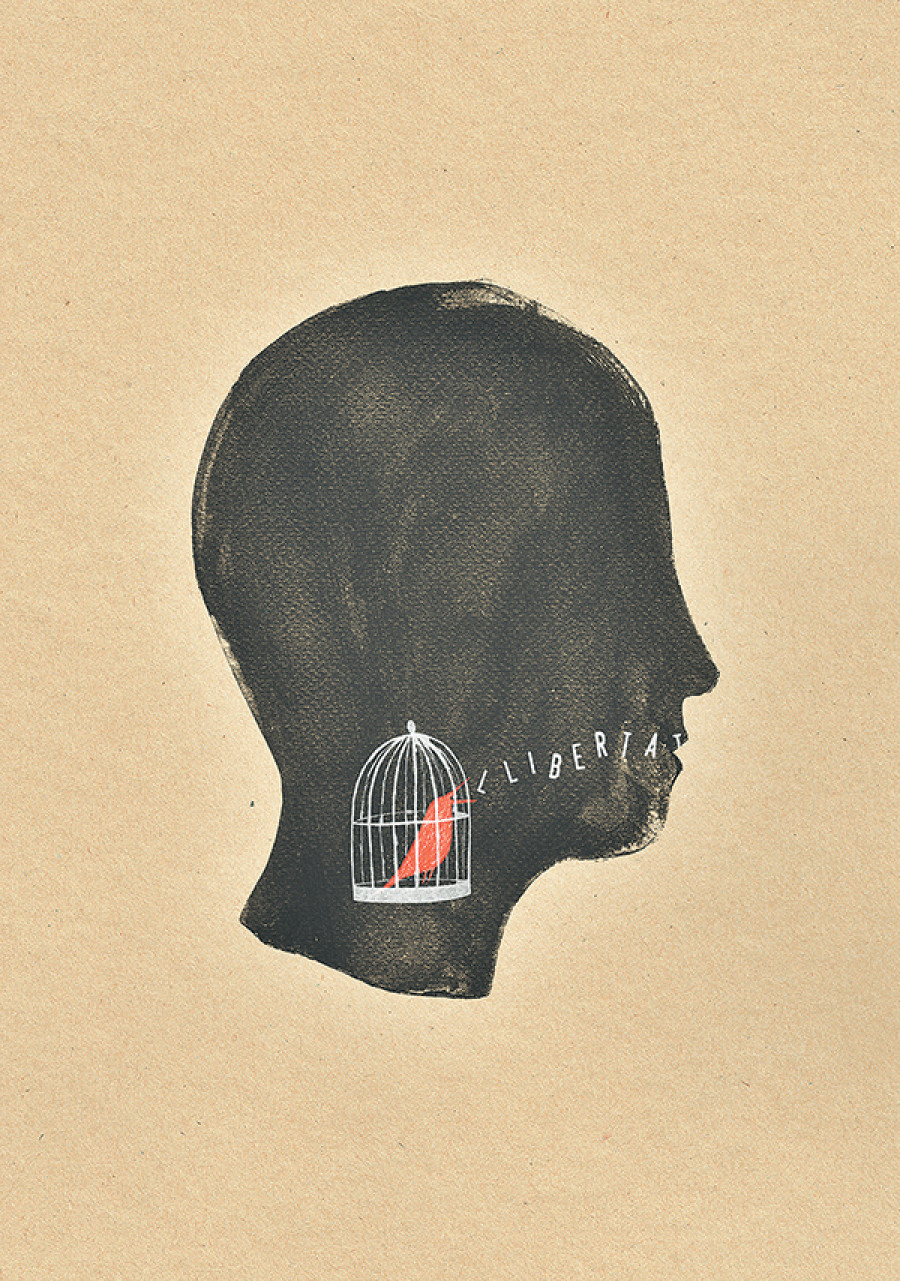

Habit of self-censorship

Hence, government and non-government actors have been equally intolerant of and violent against journalists for any sort of critical news reporting. Consequently, a habit of self-censorship has been increasing among journalists, especially among investigative reporters. During an Asian Investigative Journalism Conference in late September, several investigative journalists from Nepal said they had been living in fear after receiving threats (legal challenges, physical assaults and phone calls) during and after their news reporting. Bhrikuti Rai said she “received a very aggressive phone call from the office of the chief justice” asking her “to produce a written explanation” in court. During the conference, Sudheer Sharma,

editor of Kantipur daily, said “psychological fear among reporters is the biggest challenge in Nepali journalism.”

To sum up, government and non-government actors were found to be strategically involved in suppressing critical voices of media institutions and journalists by using threats, intimidation and systematic administrative non-cooperation. As long as state and non-state stakeholders remain intolerant, oppressive and authoritarian with regard to press freedom and the people’s right to free expression,

open and liberal legal provisions cannot make noticeable changes. Therefore, administrative officials, security personnel and political cadres need special orientation to make them respect and uphold the people’s constitutional rights of free expression and press freedom. Otherwise, press freedom will remain a myth in day-to-day practice because of the unchanged mindset of stakeholders despite broad legislative measures.

Acharya, a researcher on media ethics and accountability, is affiliated to the University of Ottawa, Canada. He can be reached at [email protected]

20.72°C Kathmandu

20.72°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)