Opinion

Book martyrs

Today the space for our libraries is ill-managed, ruined, or permanently gone

I have entered the Tribhuvan University Library of Kirtipur so many times after it was thrown into chaos by the big earthquake of April 2015. Visiting the library on the

second day of the year 2017 of the Gregorian calendar, I felt a sense of reaching nowhere with books read or unread, touched or visualised. One does not read all the books in one’s own collection, let alone those of a big library. When my late sister Khujdi entered my home library to see me struggling to reorganise it after the earthquake effect, she asked me, “Brother, have you read all these books?” When I said no, she left the room more confused than ever.

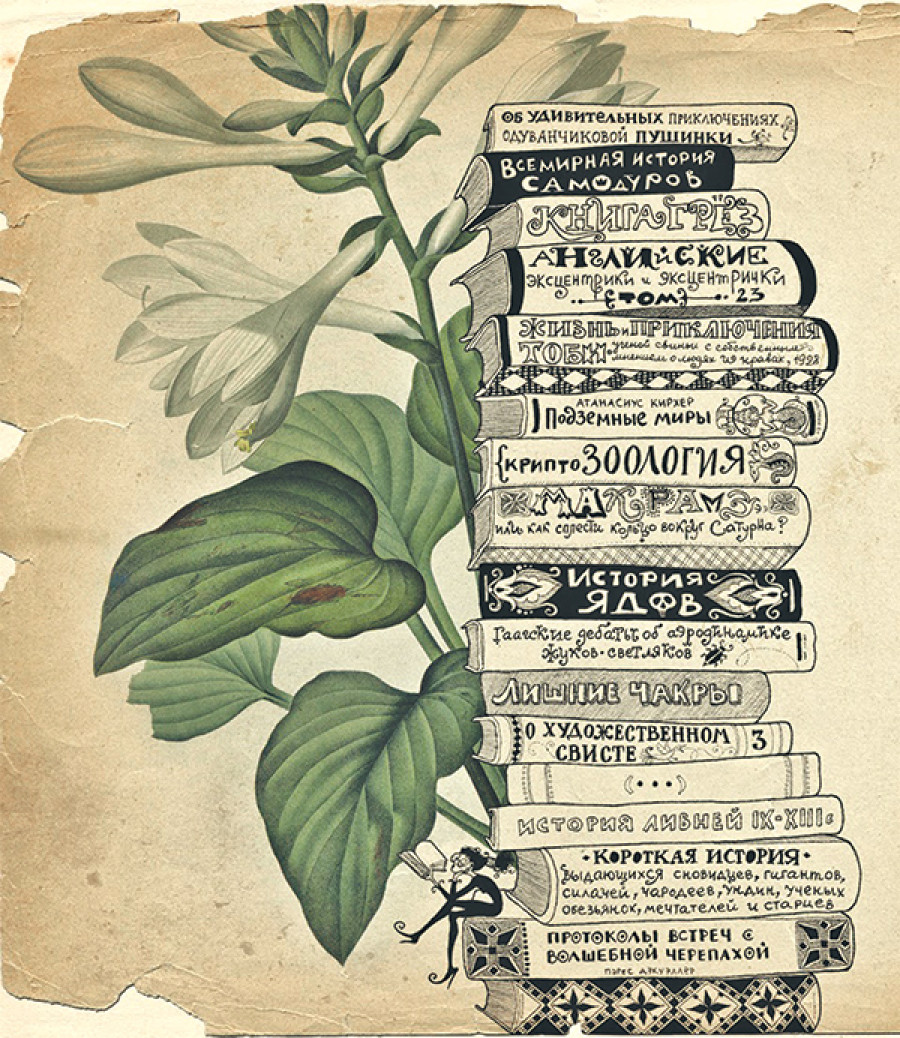

But that question came as a satori moment for me. A library, an archival collection, sits there as a latent force, a hurricane that is trapped, a box of light that floods out if you know how to open it, a seat of fugitive martyrs who have suffered so many dreadful attacks in the history of mankind. Books have always attracted the dictators and the fascists. Hitler’s fascism targeted books. Just before the total control of Germany by the Nazis, the young Germans were pulling books out of the collections and burning them. I was stunned when I was reading for a seminar paper about libraries lost from ancient times in history, and about the burning of books by states, thugs, vandals and ideological and religious groups across time, most alarmingly in the last two centuries, and the continuation of the auto-da-fe´ of the living cultural bodies in earnest in the short span of the 21st century.

Books and Nepal

Finding similitude of book destructions with the burning and destruction of human beings by states is alarming. Oxford English Dictionary coined and gave entry to a word ‘libricide’ to liken the ‘killing of books’ to the killings of people and ethnic groups known as genocide and ethnocide. Such libricide is a state-sponsored terrorist act. Libricide, which includes the killing of archives and precious human cultural collections, is carried out more in the 20th century. I was surprised to see the photograph of a Nepali man donning a cap from my Terathum district squatting, apparently trying to salvage charred books, on the cover of a book titled Lubricide written by Rebecca Knuth and published by Praegerin London in 2003. Nepal appears once in the entire book in this sentence—“by the thirteenth century, when Buddhism was disappearing from India and dwindling in Nepal, Tibetans felt uniquely privileged to be the guardians of the entire corpus of their religion, probably the richest collection of religious literature in the world.” I have found the reference to such historicity earlier while writing a book on a Japanese monk Ekai Kawuchi in 1999.

The history of books in Nepal is a big topic, but a few historical conundrums as to the history of books and the attitude of the state and of individuals towards them is worth mentioning here. The meagre stock of Tribhuvan University Library increased after the merger with the Central Library of Lal Durbar in 1962. The library grew in proportion, size, collection, extensions and cooperation. I feel nostalgic about my student days every time I enter this great space. The other day, I was shocked more than ever when I visited every nook and cranny of this library. Piles of books are thrown together like bricks on a construction site; some look like rubbish for want of care. I had thought that construction work would have begun by now. Cracks on the walls and above the doors and entry points look threatening. I was only glad to see that they have not started the so-called retrofitting that would have created camouflage and hidden the dangerous cracks. Nothing short of a total reconstruction, and some repairs where it is considered safe, can restore the library. Not even minor construction work should start without proper check of the building by good engineers.

Seek the answer

The worrying question is—are people interested in libraries any more in Nepal? The answer as to the position of the Tribhuvan University Library is that if you are not interested in this library, why do you pretend to have any interest in the university itself? If you want to close the library, close the university along with it. I mean, the answer to the question is very straight. But what about Kaiser Library, Central Library and other libraries that have a significant collection? To answer that question, I would return to the Nepali bibliotheca conundrum. A Rana person of the A class category in the family hierarchy named Kaiser Shumsher started his collection

during his father’s oligarchic reign. I remember several of the late literary writers including Ishwar Baral, Kedarman Vyathit, Balakrishna Sama, and Keshavraj Pindali telling me that Kaiser Shumsher Rana was passionately interested in knowledge and library. He developed the idea of making a private library after what he saw in Britain when he visited Britain with his father, Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher in 1908. The library, which was visited and used by the Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, the French scholar Sylvain Levi, and the British historian Perceval London, continued in that shape up to Kaisar’s death in 1964. After that, his wife and son handed the land with 50,000 books, documents and pictures to the government. A bibliography prepared by the late Lindsey Friedman and Saketbihari Thakur about books on Nepal in that library stands on the shelf today only as a spectre with most of the books gone.We have seen the slow attrition of the library over the decades. The last earthquake has brought it almost to the verge of disappearance. Television reports are showing that the National Library is scattered and dumped in satchels over some places in Gaushala. The Kathmandu Valley Library, of which I am also a founding member since it was registered on September 25, 2003, has been standing piling up books in a narrow space in Bhrikuti Mandap since July 9, 2005; it is managed by a dedicated librarian Jujubhai Dangol.

Today these spaces are ill-managed, ruined, or permanently gone. A question arises: has our evolution of libraries, which were created by people of the earlier generation who could provide big houses, become anachronistic in a reverse order? Why could the government not make the best use of these libraries? Was the library a concept that was not working in tandem with the government’s educational schemes? Did the government always act as an aputlali (taking properties of those who do not have inheritors) taker but not as a manager and a responsible agency? Is the loss of the aputali culture the loss of everything because there are no plans? We should seek the answer.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu