Opinion

Anxiety and originality in art

Paintings by the senior artist Kiran Manandhar and his son, a talented and familiar younger generation painter Sagar Manandhar, are on display at Nepal Arts Council.

Paintings by the senior artist Kiran Manandhar and his son, a talented and familiar younger generation painter Sagar Manandhar, are on display at Nepal Arts Council. This exhibition speaks about legacy, sharing and diversity in works of art. It is nothing new for artists in Kathmandu Valley to carry the legacy of a family’s male artists. This is especially true for the Chitrakars, the traditional family artists who do not normally bequeath the legacy of the craft to its female progenies. In this regard I found an interesting example of the senior female artist Sharada Chitrakar and published a review of her works (‘Sharada Chitrakar’s odyssey’, July 24).

In Nepal, it is difficult to theorise this question of patronage and legacy in arts. Nor is it easy to apply the critical theory of the anxiety of influence, which comes from a theory productively used by a literary critic Harold Bloom who has discussed the sometime crushing effect of the stronger predecessor. In this exhibition of the paintings of father Kiran Manandhar (18 paintings) and son Sagar Manandhar (41 paintings), neither the family legacy nor the anxiety of influence appears to be applicable.

This is a different situation. In this short review, I want to show how these two artists paint different motifs and how very different their discovery processes are. My strength is my personal interactions with both of them. I have written about 15 catalogue essays and reviews about Kiran Manandhar’s paintings which have already spanned about three decades. I have also reviewed Sagar Manandhar’s works.

Sheer joy

Time was my most dominant guide when I was visualising these art works in the studios of these artists some weeks ago. The studio where I went to see them was the familiar museum-like abode of these painters over a rolling hill, a couple of miles below the Swoyambhu monastery. To me the house and the studios replete with the old and new canvases and the accoutrements necessary for a working artist are a familiar sight, which means my association with Kiran Manandhar has metaphorically become my own history.

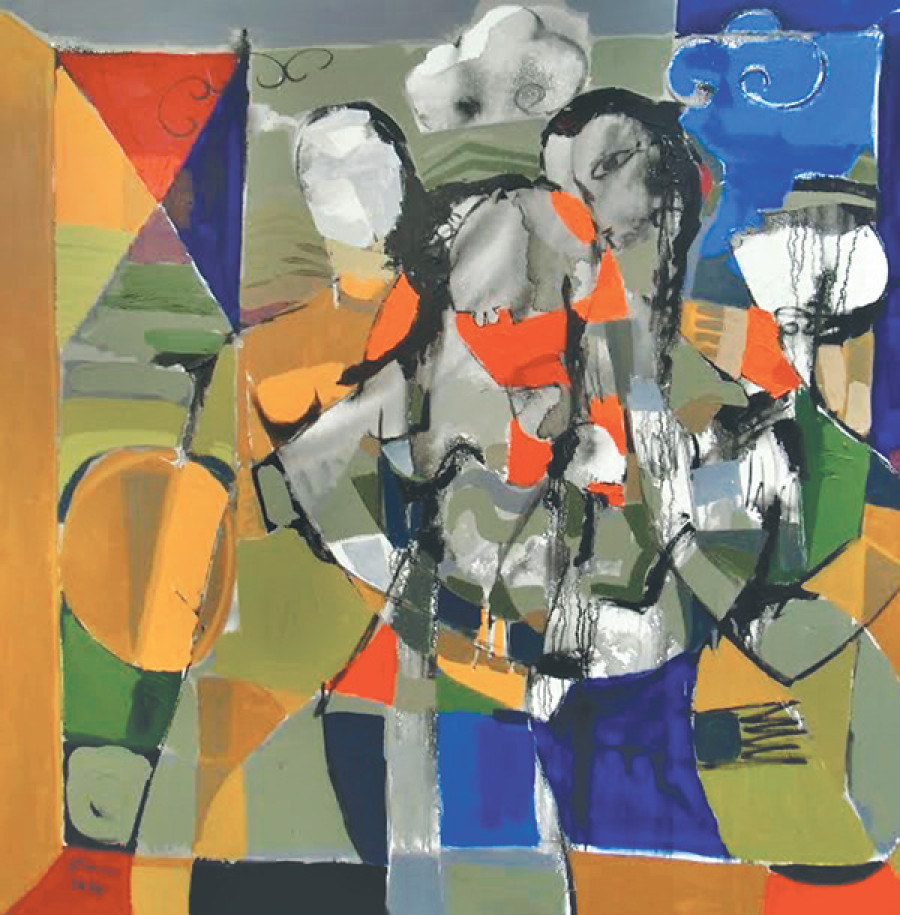

These big canvases represent Kiran Manandhar’s paintings in a number of ways. First they show his full work, a sweep of brush strokes pervasively on the canvas, usually covering even the field of action. Stylistically, Kiran has used the anthropomorphic forms, the human figurality standing in the twilight zone of realism and abstractionism. Figures move in these twilight zones. The semi-abstract avatars of the human persona in his paintings speak one aspect of his philosophy clearly. The artist’s long experience speaks here. That philosophy cuts across the anthropological and cultural dimensions of studies.

In other words, Kiran Manandhar, after decades of his dedication to art, appears to have seen very clearly that an artist should never waver from showing the human element and their movement in the paintings, because such human representation saves art from slipping into meaningless formalism. After some time, what holds a work of art from becoming a mask is your love for human essence. In Kiran’s paintings, the characters are moving in the twilight zone. He experimented through Mandalas, which ranged from recognisable to abstract forms. Then he experimented with different spaces where he moved, saw or inhabited. The third type of his experiment comes from his sheer joy of executing paintings. That is the reason why he dashes off several canvases in group works or in painter/poet meetings.

Sagar Manandhar grew independently of his father’s influence, albeit he grew under his apprenticeship and completed his post-graduate studies from the same Banaras Hindu University of India. In the present series of paintings, Sagar has followed the images of the famous iconic deity of the Nepal Mandala called Bhairav. In these paintings done in oil pastel this time—a change for him—Sagar has followed the evolution of Bhairav as a mytho-poetic motif. He has used his perception, a mytho-poetic mode of cognition, to discover the multiplicity of Bhairav manifestations, including the human face behind the deity’s mask popularly known as Lakhe.

Forms of Bhairav

In the present Bhairav series of paintings, Sagar has returned to the permanent abodes of the deity. He said to me “there is ambiguity in history and the cultural interpretations; there is ambiguity in paintings. But I was struck by the synchronicity of the ambiguity in art.” That speaks a lot about Sagar’s perception of modernity in art. He can present a narrative behind the discovery and creation of each of these paintings. The iconic figures, the astral images, especially the sun and the moon, and the manifestations are all Sagar’s motifs in these paintings. The black abstract bands and the dark textures of the Bhairav icons have found treatment in his paintings.

In nearly all the works, we can see strong dark swaths cutting the canvas aslant or vertically. From the Batuk or baby Bhairav to other ferocious forms, the artist has depicted the time and space occupied by the deity. Before painting the Bhairav canvas, Sagar developed sketches as part of his method and played with the various clear and diluting forms that make up miniature drawings. The greatest technique he has used in these works is the application of strong brush strokes, which perhaps represent Sagar’s intense mood of dialoguing with the deity Bhairav. Stiff and disciplined forms appear in the paintings. In the Bhairav painting, Sagar represents what in Newari is called interconnectivity, which is the general theme of all these paintings.

Through monochromatic or multi-coloured strokes, some representing musicality, or the devotional ambience through the use of yellow, Sagar Manandhar has created the very dynamism of the iconicity and various manifestations of the Bhairav in these paintings, each of which lurks a movement that becomes complete in the viewers’ perceptions. Technically, and in terms of the delineation of forms, these canvases are consummate, and they represent the young-generation artist’s originality and confidence in experimenting with aesthetic forms, and above all, in the discovery of the latent creative dynamics of the long familiar cultural icons.

This joint exhibition is itself a notable artistic experiment.

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu