Opinion

Toxic priorities

By ignoring hazardous air pollution levels, government entities are actively creating a public health disaster

Samik Adhikari

Last December, when the air pollution level turned dangerous in New Delhi, it created a political crisis of sorts in the Indian capital. Several hard and unpopular decisions were taken. The Arvind Kejriwal-led New Delhi government implemented an odd-even pilot scheme, whereby vehicular movements were restricted on certain days. More importantly, numerous additional monitoring stations were set up and policy organisations provided analytical assistance to take stock of the pollution data. Six weeks later, air pollution was curbed by 15 to 25 percent, according to popular measures of monitoring harmful air particles.

Compare this to the situation in Nepal, and you will quickly begin to realise that we are several years behind in the realm of active policy-making. For starters, our government does not even systematically monitor air quality data in Kathmandu and surrounding areas. In 2002, the Danish government had installed seven air quality monitoring stations in the valley, but all of the devices were rendered obsolete by 2007. Plans are now underway to install at least a dozen air quality stations by the end of 2016. But initial attempts to install three of them in Kathmandu, Lalitpur, and Kavre recently faced several hurdles, including the favourite excuse of “software glitches”.

According to a 2014 report by the Clean Air Network Nepal, a majority of the PM 10 emissions in the Kathmandu Valley result from vehicular emissions and roadside dust. One only needs to see the gust of black smoke coming out of public buses, trucks, old microbuses and private vehicles

to get an idea about who the main perpetrators are. And one of the biggest culprits that let these vehicles ply the roads is the pollution control authority within the Ministry of Population and Environment which issues green stickers to vehicles despite the obviously hazardous amount of harmful smoke they emit.

Two primary causes

There are two leading causes of why these vehicles are not kept off the road.

The first one is corruption, an age-old problem in Nepal. There is no sector of considerable importance in the country that is free from corruption, be it education, foreign employment, post-earthquake reconstruction, or the agency to control corruption for that matter.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the emission testing procedure is a hoax. The driver hands out his bluebook along with a 1,000 or 500 rupee note, and most times emission standards are passed without a single inspection of the vehicle. And it makes sense. It is a classic case of the tragedy of the commons where pursuing individual benefits while dealing with a public good—the environment in this case—leads to a sub-optimal outcome in the end.

Another reason which keeps old- and sub-standard vehicles on our roads is the presence of transport cartels, which are powerful actors in the political process with an ability to mobilise large crowds during the election cycle. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the transport ‘mafia’ keeps a number of politicians in its pockets and uses them at its will—for example, when confronted with the sub-standard emission standards in the vehicles they run. And here again, powerful unions

acting in the vested interests of a few political actors are rife in many important sectors, be it transport, education or tourism. There is a detailed account of Nepal’s unions, cartels, and syndicates in Kul Chandra Gautam’s book Lost in Transition. One of the biggest demands raised by Dr Govinda KC through his hunger strikes is to curb the influence of these groups.

Beyond measurement

Air pollution is not merely an issue of inconvenience anymore; it has real consequences on millions of lives. Just last week, the World Health Organisation released a report saying air pollution kills almost 6.5 million people globally every year. In 2014, the Guardian claimed that Kathmandu was on the verge of being “unlivable” because the level of small particulate matters at peak hours had reached 20 times that of the WHO’s safe upper limit.

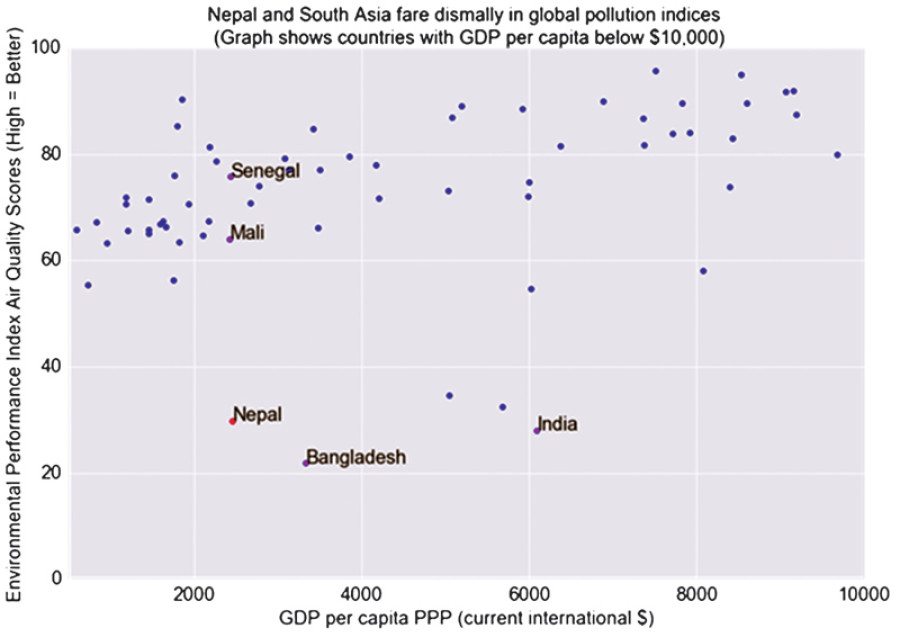

Unlike Beijing, Delhi, or even Dhaka, Kathmandu cannot blame industrialisation for its air-pollution levels. And extrapolating that further, Nepal has won the non-coveted title of being the poorest country with the worst performance in last year’s air

quality rankings in the Environmental Protection Index (EPI). To put it into perspective, Nepal has the same GDP per capita level, measured in current international dollars, as Mali and Senegal. But its air quality level, according to the EPI, is almost three times as bad as its income peers.

As we stand on the edge of another festival season in Kathmandu, one cannot help but fret over what pollution has done to this once charming city, with moderate weather, a clear view of the majestic hills, and easy commute from one end to the other. Over the last 15 years, what Kathmandu has turned into is a textbook example of how unbridled capitalism and mis-management of city resources have given birth to what is unquestionably a public health disaster now.

The only silver lining in all of this is that not all the effects of air pollution are irreversible. But it requires an unparalleled level of effort and management to right the wrongs. It has to start with monitoring the level of harmful particles in the air. But measurement only will not amount to much. Since the air pollution in the valley is caused to a considerable extent by vehicular emissions, hard decisions will need to be taken to keep old and unregulated vehicles off the roads. The practice of digging and leaving side-roads unpaved for months at a time has to end. There has to be a mechanism through which civil society can register complains against any violators. And perhaps, every now and then, the people who have let the conditions in the valley to deteriorate to this level need to roll down the windows of their air conditioned vehicles and inhale what the masses have been inhaling on a daily basis for a long time.

Adhikari, a graduate of Harvard University’s MPA/ID programme, is a consultant for Unicef, Nepal

17.9°C Kathmandu

17.9°C Kathmandu