Opinion

Lost and found in translation

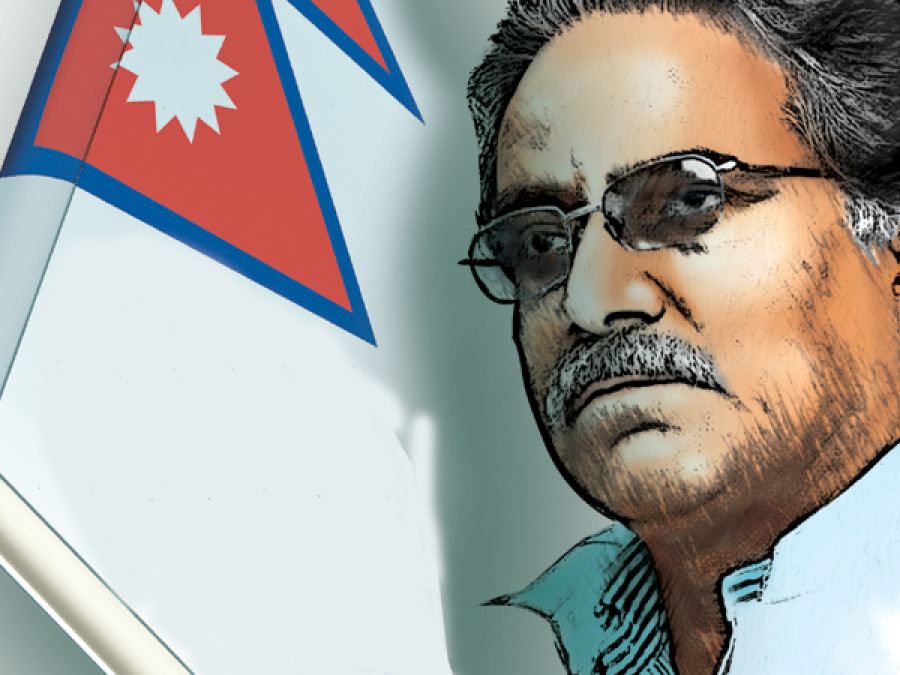

No one would think of Prachanda as being illustrious but that is one meaning of the word

Deepak Thapa

The main problem with the issue of an unwritten pact between our politicians is getting the spirit itself wrong in the first place

Now that Pushpa Kamal Dahal Prachanda seems likely to hog the centre-stage of national politics once again, it is perhaps time to trot out an article idea I have had for some time. This involves trying to understand the man through the meanings attributed to the name he had adopted in his revolutionary zeal and which he has since formally appended to his own.

In the early 2000s, the world at large unexpectedly discovered a raging Maoist insurgency in Nepal when the international media arrived to cover a regicide. Led by a shadowy figure whose only known photographs numbered two—that, too, from years earlier—and shrouded in all kinds of stories about who he really was, it seemed only apt that he was known as “Prachanda”, with the most common translations latched onto by journalists being the “Fearsome One” and the “Awesome One”.

As sometimes happens, a few years later, while the conflict was still going on, I was approached by a very well-known international magazine to vet a story on the Maoists for inaccuracies, misrepresentations and the like. The following is a verbatim excerpt from one of my quick comments on a sentence that read: “…Pushpa Kamal Dahal, who assumed the nom de guerre Prachanda, or ‘Fierce One.’”

I wish you would not translate the name. No one thinks of Prachanda as personifying what his name means. In Nepal, every name has a meaning as do many other cultures, but it hardly means anything. And there is no indication that the noms de guerre are chosen for any particular reason. Among the names Maoist leaders have taken are, in translation: Third Son, Cloud, etc, although some have chosen more “revolutionary” sounding like: Creation, Revolt, etc. A journalist began this translation business and everyone seems to have taken it up for no rhyme or reason. For instance, no one translates David as “Beloved of the gods”. But if you have to, you might as well stick to Prachanda only and get rid of what have been provided for Diwakar and Bijay. Or else you would have to translate everyone of those names: Prabhakar, Ranju, Ilaka, etc.

Anyway, this translation of Prachanda is not quite correct. The dictionary meaning provides the following alternatives, all of which are correct.

- unbearable

- fearsome

- extreme/bright

- strong

- hard

- unbearable

- big/large

- extremely hot

- prone to fury

- illustrious

- sharp

- long

Until Prachanda came into the scene, for Nepalis, the word “prachanda” meant “illustrious” since it figures in our national anthem, which is a paean to the king. “Fierce One” just seems better copy and so many people have used it, but I would not use it so unquestioningly.

The translations provided above are my own and there can be grounds to quibble with my understanding of these synonyms of “prachanda”: sahananasakine, darlagdo, ugra/tejilo, baliyo, sahro, sahinasakine, thulo, jyadatato, jyadairisaha, pratapi, tikho/dharilo, lamo, and mapako [also meaning fearsome]. The dictionary I cited is one of the more reputable ones, and obviously other dictionaries can have alternative meanings. Until the man himself clarifies what the “prachanda” in his name signifies, and even he may not be able to actually pinpoint any one meaning, we are reduced to guesswork and can pick and choose as we please.

I did not explicitly use terms like “Orientalism” to get my message across to the magazine but it certainly was disturbing that the magazine had tried to jazz up a story for that extra effect even if it involved, perhaps unknowingly, stretching facts a bit. Apparently, old habits die hard even in a publication that had in the past received a fair amount of flak for its depiction of “natives” outside the western world.

Stool conference

Translations are fraught with traps. As a young language, Nepali is still adopting useful words and other jargon from different sources, mainly English but also Hindi. And, the translations have not always proved faithful to the original.

Let’s take the idea of the “roundtable conference”, popularised by the Maoists since they first explicated it just months before the palace massacre. The “roundtable conference” is part of India’s political vocabulary because of three such meetings held in London in the 1930s to discuss British India’s future. It was translated as golmejsammelan in Hindi, in which “mej” means “table”. Unfortunately, “mej” sounds uncannily similar to the Nepali “mech”, meaning “chair”. And, so when our political leaders, most of whom have become versed in political texts through the Hindi medium, brought the concept into Nepali, it became golmechsammelan, or “roundchair conference”.

While there certainly are round chairs, much more common are the round stools, and for any number of years, I could not get the image out of my mind of the likes of Girija Prasad Koirala, Sher Bahadur Deuba, Madhav Kumar Nepal and Prachanda perched on round stools as they discussed the future of our country. As it so happens, it has even lost its literal meaning by now, and golmechsammelan now stands for a roundtable conference.

Gentlemen and their word

One more example is the “gentlemen’s agreement” that has been much in the news lately. Op-ed writers have had a field day playing with some variation of “bhadrasahamati, abhadrarajniti”, translated as “gentle[men’s] agreement, rowdy politics”, a theme that resonates very well with almost everyone in today’s Nepal.

Methinks, however, that the main problem with this issue of an unwritten pact between our politicians is getting the spirit itself wrong in the first place. “Gentlemen’s agreement” has been rendered as bhadrasahamati in Nepali, where the term “bhadra”, that is, gentle, decent, etc, qualifies “sahamati” (agreement). Hence, we are dealing with an agreement that is gentle, decent, etc—whatever that means. There is nothing that ties the agreement to the reputation of the parties concerned, of being true gentlemen and all it implied in a bygone era of foxhunts and hounds, afternoon tea and croquet, post-dinner brandy with the boys in the smoking room, and gallant chivalry, in which it was thought more honourable to give up your life than go back on your word.

Posit such a conception of a gentleman with our leaders, and one certainly understands why those agreements are better off called bhadrasahamati, instead of the more awkward but accurate construction bhaladmikosahamati.

23.02°C Kathmandu

23.02°C Kathmandu