Opinion

Between two worlds

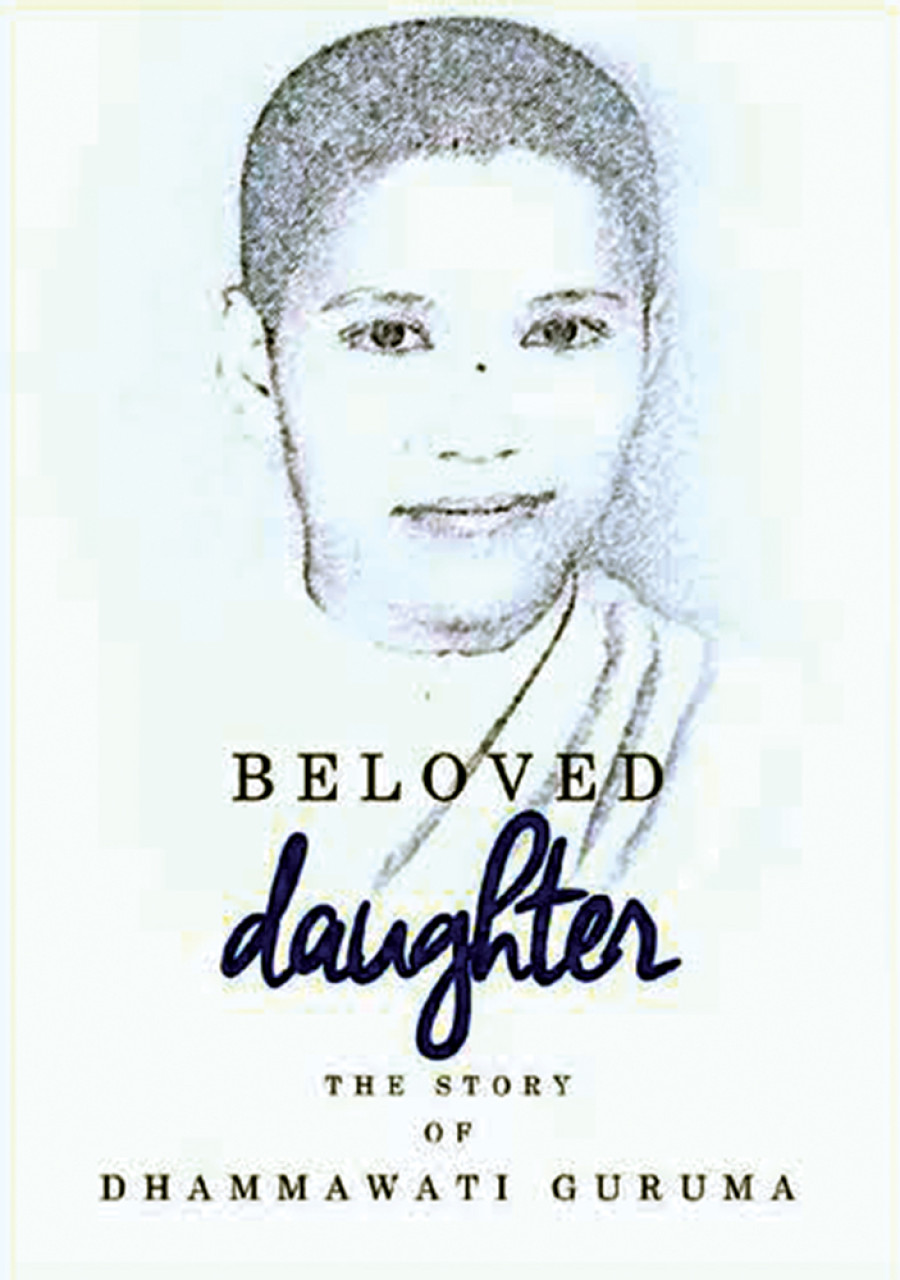

The biography tells how a girl ran away from home to look for wider horizons in a staunchly patriarchal society

Mallika Shakya

It was such a great honour to have been asked to speak on my aunt as our family’s representative at the launch of a book on her on July 12. But ‘family’ is a contentious issue, especially when speaking about someone who actively renounced her home to embrace the world. Does one still need this feudal-bourgeois unit to guide us in today’s day and age? Need family be biological? Can there be other kinds of families?

As an anthropologist, I have drawn family genealogies of my informants but have struggled at times to identify with my own biological genealogy. I can never deny my bonds with those who gave birth to me and brought me up to be who I am today. What bothers me about the way genealogical charts are drawn is that they list women as consorts, not independent beings; genealogies begin with a great grandfather and his wife, then a list of his sons and their wives, then their sons and their wives, and so on and so forth.

Growing up, I was lucky that I knew a woman who did not fit into this rigid mould. My aunt Dhammawati Guruma always commanded a place different from other women. She looked different and people talked to her differently. This I have known about my aunt from as long as I can remember, well before I learned about her nunhood, her faith and her now-legendary journey through the dark forests, out there in Nagaland and Burma, and in here in the deepest recesses of her conscience.

An alternative genealogy

The person who introduced me to this side of radical womanhood that my aunt embodies was my mother—the aunt’s brother’s wife, who lives a fiercely private and simple life, but somehow still manages to radiate a sense of independence beyond being a wife-consort. I am then reminded of my aunt’s best friend Gunawati Guruma, or Magunma as we fondly called her, a Burmese nun who accompanied my aunt most of her life, sharing nunly duties and social activism until recently, before taking a very late retirement back in her country. When I connect these three dots of women, there emerges a new genealogy, which is a lot more agreeable to me than the original one.

The possibilities that a little girl, even in a staunchly patriarchal society like the one I come from, can think of a family that upholds her aspirations and potentials, came from my aunt’s big departure that forms the core of this book. Her biography, “Beloved Daughter: The Story of Dhammawati Guruma”, a translation from the original Burmese to Newa to Nepali and now in English, tells how a 14-year-old ran away from home to look for wider horizons. Her initial pursuit of literacy and knowledge later led her to an alternative life where Buddhist renunciation was entwined with feminist pride, academia with compassion, and nunly duties with a radical agenda for social reform. She did come home after a decade and a half—not as a daughter though, but as a nun.

A family legend

My aunt was the only daughter in the family. After she left, our family stopped having festive reunions or nakhatyas, an essential part of Newa social life where the daughters of the family who had been married off with just a dowry but no ansha or family property, would visit home for a generous meal and a hearty get-together. This vacuum turned my aunt into some kind of a family legend. She then became part of my bedtime story. I did not read Cinderella when I was young; I listened to my aunt’s fairy tale about exploring and finding our own meanings.

After two generations of a shortage of females in my family—my aunt was the only daughter of my grandparents and my grand-aunt the only daughter of her parents—my generation is abundant with girls! Very few of them read Cinderella. Most grew up with the aunt’s fairy tale. Most are now raising their own daughters, and with them travels the tales of women who paved their own paths to the destinations of their own liking.

There have been times when I hated the idea of this rebel aunt because the bar had been set so high. But looking back in life, there is so much to cherish about having an aunt who showed us that a proto-woman cannot be scripted in patriarchy.

Relevance of rebellious stories

Quite a lot has happened in Nepal since 1949 when Dhammawati Guruma left home to avoid ending up becoming someone’s wife-consort. We have ousted the Rana regime, then the Panchayat, and after a brief democratic stint, we now have this post-revolution regime that still denies women the right to confer citizenship to their children.

Rebellious stories of runaway women remain relevant today. I truly hope my nieces will continue to listen to my aunt’s fairy tale, of a different kind that would make their Cinderellas feel a little uncomfortable. I hope to also learn about other women in other families, who embody fairy tales that are different from both Cinderella and Dhammawati, so that little girls have a lot more to choose from and young women a lot more to aspire to.

I am also grateful to Dhammawati Guruma for allowing us to continue to call her our aunt. She renounced her biological family; yet, when I was lost one day, she counselled me out of my emotional mess. What she had told me one sunny, dusty morning remains my armour of self-protection: that one cannot choose whether one wins or loses a fight, especially when the rules are stacked against you as a woman, but you can choose which battles to fight and what to let go, or even what to run away from. This helps me find my dignity and my meaning without losing myself to the endless misery of this world. I am sure others in the family have drawn their own wisdom from her life, deeds and words. We are forever grateful that we have her in this way.

Shakya is an economic anthropologist and Assistant Professor at South Asian University, New Delhi

22.12°C Kathmandu

22.12°C Kathmandu