Opinion

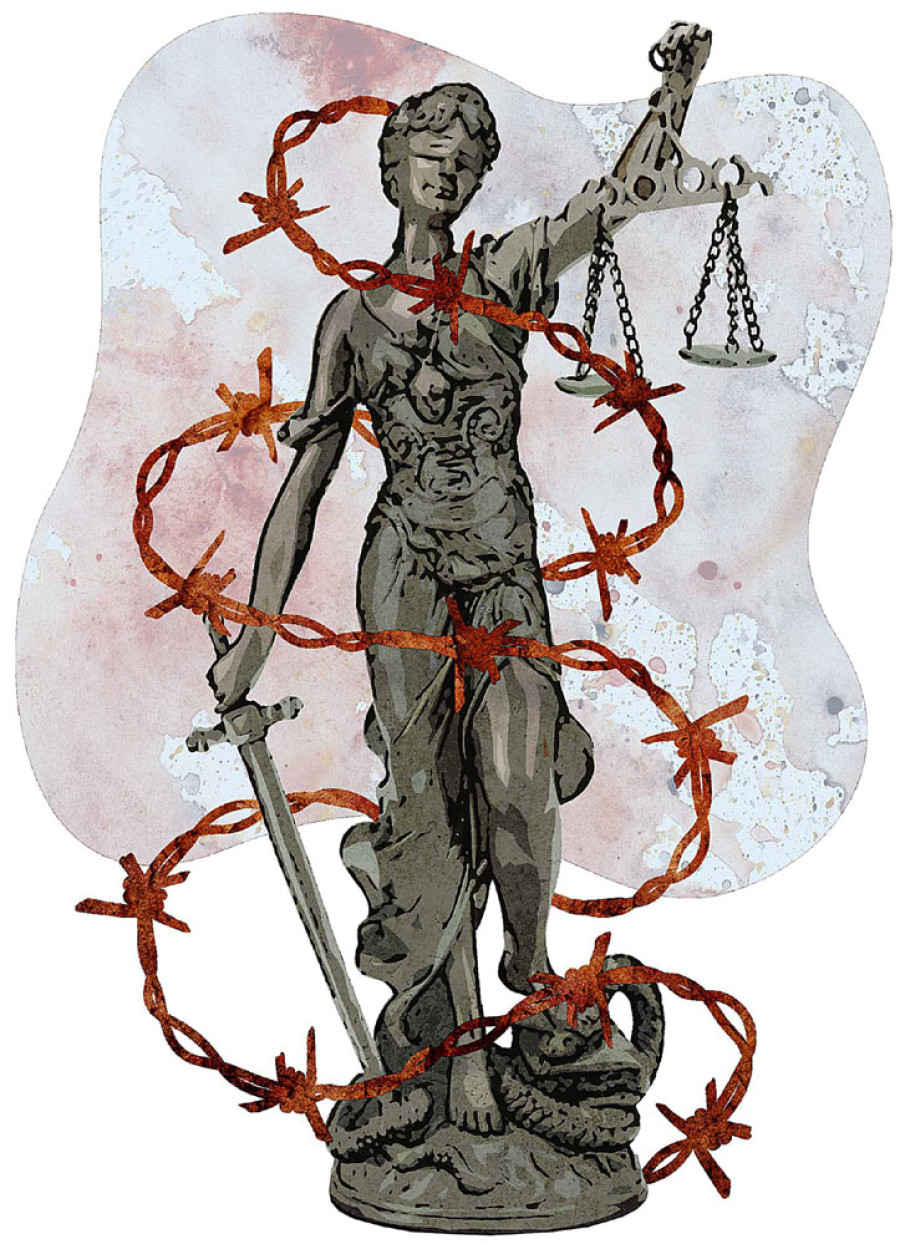

Transitional justice

The notion that a process that excludes victims will address their needs is a fantasy

Ram Kumar Bhandari

Myths concerning both the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Person permeate Nepal’s transitional justice debate. The myth, disseminated if not believed by the political elite, that the two commissions will solve all the problems and act as a panacea, the idea that an institution in the Capital can address the entire range of impacts of the violations committed throughout the country, and the notion that a process from which victims are excluded can meet their needs are all being increasingly exposed as fantasies.

After one and a half years of the commissions, it is clear that they will not resolve the disputes, address the victims’ key demands for truth and justice or create a sense of equality and support. Considering the highly politicised nature of the commissions and their simple incompetence, assumptions that they can address the issues they have been tasked with are unrealistic. The victim community has been repeatedly demanding an amendment to the Commission Act respecting both the Comprehensive Peace Agreement and Nepal’s international obligations. Senior political leaders and the state, with the Commissions watching from the sidelines, are working on secret amendments without consulting the victims and putting the elite over them.

Maximise victim engagement

This is one last chance to correct past mistakes and develop a partnership with the larger victims’ groups for wider legitimacy of the entire transitional justice process. Without ensuring the rights of victims to truth, justice, dignity and representation, the flawed process cannot take the correct course. What obstacles have prevented the state and major political parties from including them in the transitional justice process? They have not only created an environment for locally driven community reconciliation but also contributed to ensuring widespread registration of complaints. Ironically, the one great success of the transition has been the creation of a movement of victims that has transcended political allegiance and created non-party approaches to address issues remaining from the conflict.

The commissions, state and parties must learn from this mobilisation and approach of victims to localise transitional justice and maximise victim engagement. All the victims’ concerns and the fundamental principles of transitional justice—as understood in the Supreme Court directives—must be incorporated in the act amendment process without delay. The transitional justice process is driven by political narratives rather than a constructive engagement among potential actors. A systematic approach demands that problems are assessed in conjunction with the victims themselves, and local and informal processes established to complement the ongoing national, institutional mechanisms. There has been little effort to address victims’ needs in a sustainable, comprehensive and inclusive manner.

Dual responsibility

Transitional justice commissions are not courts of law, nor do they have the power to bring individuals to trial. Neither the commissions have been able to build civic trust or create an environment for victims and the broader society to discuss the past openly. They have failed to stay true to their mandated norms, such as their supposed independence, victim-friendly character and simple competency, or follow the ethics of a humanitarian approach to transition. The commissions should create a safe space to share stories of suffering and allow victims to recover a sense of dignity and recognition. Victims throughout the country have said that they need to modify their attitude and their approach should be transformed to internalise a responsible and ethical relationship. If we all contribute to supporting a victim-centric approach to truth and justice, it can initiate deep social changes and serve both victims and the wider citizenry.

Nepali victims have chosen a strategy of nonviolence against injustice, seeking not to take revenge or adopt a confrontational path. The political parties and the state must have a clear vision of what these commissions are meant to achieve. Politically, the commissions must be recognised as crucial institutions for the nation’s healing, socially, they must have a degree of legitimacy, particularly among conflict victims. Society will also benefit from a better understanding of history and the truth. This will be knowledge that can help prevent future violations and address the pervasive structural violence that fuels conflict.

Way to go

The government and ruling political party leaders in Kathmandu must listen to the demands of rural conflict victims who have been fighting against the state’s negligence and injustices. They remain in a state of exclusion, poverty and social injustice that keep them disappointed by the ongoing process. The poorest communities like Tharus, Madhesis, Magars and Karnali residents who sacrificed so much during the conflict have seen no significant change in their lives. The course must be corrected by ensuring victim participation and representation in the current amendment as per the Comprehensive Peace Agreement and principled transitional justice approaches.

A lot will depend on how the state reacts and the major political actors manage to reconstitute themselves. It is highly important to take stock not just of the superficial commission model but the process too. Any action to redefine a long-standing contentious issue of justice for victims and accountability in the country’s transition requires deep thought and serious engagement, not superficial discussions at the top. The current process of a highly centralised top-down approach, without considering the victims as primary rights holders, is a formula for chaos. It will not solve long-standing social injustices, poverty and exclusion which fuelled the conflict in the first place. It may ultimately lead to a politics of revenge where none of the actors will benefit at the end of the game.

Bhandari is the general secretary of Conflict Victims Common Platform

8.12°C Kathmandu

8.12°C Kathmandu