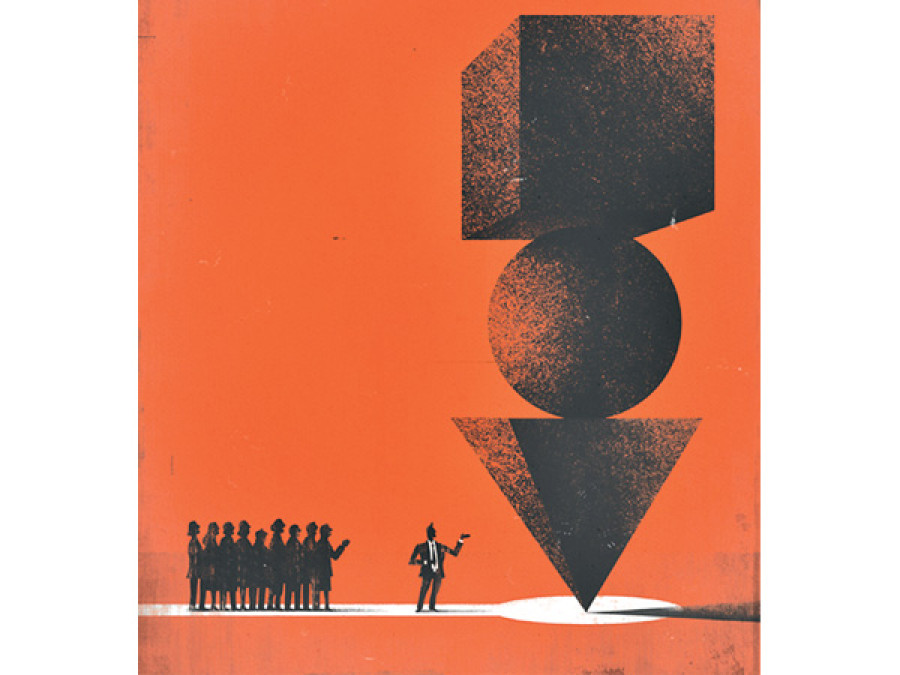

Opinion

Dream of a golden future

Fundamental reforms of the political parties are necessary if we are to ensure democracy and development

Whether it is the CPN-UML’s rise on a wave of nationalism, something that has apparently subdued Indian interventions, or the announcement of a new political party, or even the recent agreement on a Parliamentary Hearing Committee, something important is happening in our country. Nepalis are dreaming about a prosperous future with a vibrant democratic culture.

Yet, those dreams have a darker side. The earthquake victims are living without a roof for the second consecutive monsoon, discontent simmers in the Tarai, and the civil society is voicing concerns, though weakly, over citizen rights and freedom of expression.

How do we reconcile these seemingly contradictory impulses?

I would like to argue that the idea of a prosperous future and a vibrant democratic culture is a myth propagated for narrow political interests because the parties cannot deliver the promised future. And we, as well as the parties, know it.

The real barrier

Political parties are adopting a two-pronged strategy. First, they are trying to divert attention away from the problems of the present as well as the ghost of the past through the rhetoric of a golden future. Second, they are using our fears about the future to discipline the present.

Understanding this paradox is important if we are to realise our dreams.

There is a continuing debate in Nepal about why Nepal has failed to develop. After the promulgation of the constitution, political parties like the UML are making efforts to divert people’s attention to the agenda of development, claiming that the agenda of democratisation has already been achieved.

Without addressing the factors that have prolonged a state of underdevelopment and political instability in Nepal, the parties cannot really deliver the promised future.

Below, I briefly discuss some reasons why the mainstream parties will fail to deliver the promised future and why their knowledge about this inevitable failure reduces their rhetoric to a technology of power aimed at serving narrow political interests.

The logic is simple. We cannot achieve development and democracy without addressing the real barriers to democracy and development. Political parties, which are responsible for running the state, are sustaining the barriers to democracy and development. Therefore, the state will fail.

The most important factor is related to the idea of separation of powers and rule of law. One of the fundamental principles of a modern democracy is the separation of powers between the judiciary, legislature and executive and between different state organs. However, this has turned out to be a myth in Nepal’s case. The parliamentarians want to work as executives in managing constituency development funds and frequently encroach the functions of the executive. All constitutional appointments are determined by individual loyalty to the parties and are disbursed as rewards.

The appointment of judges in the Supreme Court is an example. Supreme Court judges need to be impartial and free from political influence. However, people have been appointed as judges as a reward for serving the party’s political and ideological interests. The tussle over the Parliamentary Hearing Committee, which is now filled with individuals loyal to a handful of party leaders, also explains this desire to centralise power. As a result, all constitutional bodies are filled with people who feel obliged to return the favour to party leaders. Forget the rule of law or separation of powers.

The impact of mordernisation

The structures of political parties have changed over time. Although they have become more democratic regarding their formal features, their actual decision-making and operations are becoming more opaque, centralised and undemocratic.

Mass-based parties like the Nepali Congress (NC) used to be led by party leaders with highly developed personal values. Modernisation and the rise of capitalism have corroded this system. Decision-making in the political parties are now increasingly centralised and limited to a handful of political leaders.

A handful of party leaders control party membership and distribution of tickets for public offices. Individuals, or contractors, have to pay party leaders for the tickets, either in the form of blind loyalty or money. Parties have a tendency to choose people who have a better chance of winning elections. Increasingly, they tend to be contractors and businessmen with enough power and money.

A political leader has to invest a lot to become a leader. The recent NC convention demonstrated the significance of financial clout and networks with power elites in becoming a party leader. Once an individual becomes a party leader, his first obligation is to the extractive networks, those who pull the financial strings and political leverages.

Most importantly, political parties continue to sustain political and social instability. Since the constitutional provisions and principles do not operate in real politics, the rule of law and principles of transparency are non-existent and the party in power has access to so many public resources, parties will continue to undermine the ruling regime. In addition, fears, self-interests and needs of a handful of leaders will continue to determine the fate of the country, decision-making processes, and create a division between insiders and outsiders.

No escape

If we are to ensure democracy and development, we need to carry out fundamental reforms of political parties in Nepal and make them independent of extractive networks.

Of course, we can argue that restructuring of the state and federalism takes the state and governance closer to the people. We can also argue that ultimately it is the people who have control over who gets elected. Normally, the competition of political parties in the free market is expected to sideline parties working against people’s interest as people will only vote for ‘good’ parties.

However, these idealistic principles of democracy have rarely been effective in the past because the people have no direct control over who controls the party and are forced to choose between the existing parties. Given the substantial resources and capabilities required to run a party, the presence of a fundamentally ethical and democratic party will remain a dream in the near future.

Another factor that we can cite is civil society pressure. But again, we know that the civil society is either a parasitic element of political parties or a creation of donor-funding. An independent civil society depends on the state, and an undemocratic state can only reproduce an ineffective civil society.

The only solution is to democratise the existing political parties. However, there is no constitutional provision on the basis of which the people can force democratisation of political parties. We will have to depend on the ‘magnanimity’ of political leaders to reform their parties. This, as we know, is improbable.

Khanal can be reached at [email protected]

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu