Opinion

Great visitors

It is always very productive to be awed by history as long as we know how creatively we understand its human side

The Canadian media pundit Marshal McLuhan famously said ‘media is the message’. I encountered this great aphorism when young. There were not many media outlets in Nepal during those days. After browsing through the fat memoirs of journalist and litterateur Kishore Nepal and an erstwhile journalist Ramesh Nath Pandey, we get a picture of what we had then in the form of media. My story in Kathmandu has always been a quest, which does not seem to cease. The reason as I understand now is that I had set out with a singular mission of quest from my remote village in Terathum of Limbuwan.

To be an active academic is the joy of living. Though I have been sharing my experiences with the new generation and reminding my contemporaries of the vitality of the sixties and seventies, I find recalling some minuscule moments with some unique visitors to Kathmandu would be worthwhile. I feel awed by history when I remember these visitors who came to Kathmandu at different moments during that period, and especially, when I navigate for more information about them. That is when I understand what McLuhan was implying in his aphorism. Information about these characters about whom I knew little then inundates me. I feel happy to see that I had known in essence who they were.

Many people from the West and Japan, not to mention South Asian countries, love Nepal. There is a long history to that. We felt that very clearly when we were devastated by the big earthquake last year. Now it is easier to get access to persons who come to Nepal with dreams and love. But back then, it was not possible to become fully familiar with them. In the following paragraphs, I want to present some characters to show that these people, especially from the West, did not come here entirely, as one scholar Thomas Richards says, in search of a surrogate Shangri-La.

Evoking the past

The occasion to revisit history arose with a simple communication, when a friend and poet Ramesh Shrestha, a Bangkok resident, wrote to me if I could find the whereabouts of Michael Hollingshead to write a blurb for his collection of poetry. Little surprised by his leap in history, I felt Ramesh was glibly evoking our bygone past. After some months, he himself sent me a loop of correspondence with people who said Hollingshead had supposedly died in South America in the early 90s. I knew Hollingshead as a writer of a book entitled The man who turned on the world, and as one of the bearers of the consciousness of that period. I did not know he was such a giant who introduced LSD to Timothy Leary, a genius known so well in the Anglophone world and beyond. He lived in Dhokatole, Kathmandu in one section of the palatial Gurju house with a woman named Oriole. Impressed by him, I became a regular visitor to his place. He accepted my request to give a talk at Kirtipur. When I introduced him with his book, I did not know about his odyssey as much as I know today. Addressing to our needs in the English department, Hollingshead spoke about the British history since the 40s, and he chose to speak about Raymond Williams, the guru of cultural studies. That was my first exposure to cultural studies and creative history that I have always shared with my students.

Lord Shiva’s justice

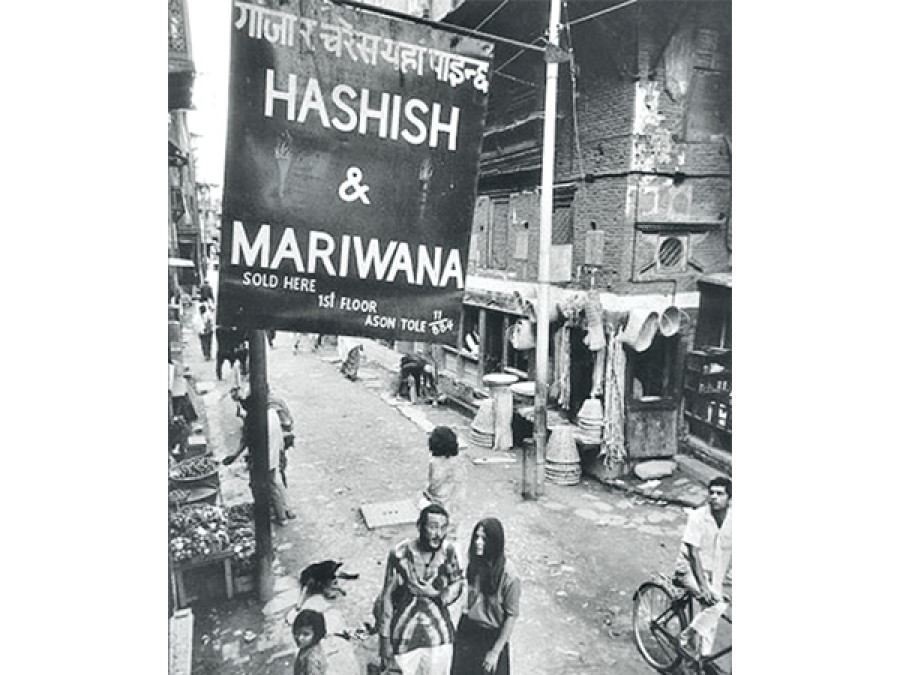

The next person was Ira Cohen who lived in another section of the Gurju complex. This New Yorker was a poet of unique order and a photographer who used mirrors while taking pictures. I was awed by these mirror photographs and had no clue about the process. He was perhaps the last loiterer who left Nepal in 1974 heart-broken by Nepal government’s prohibition of the free sale of ganja. In a ‘mirror poem’ oddly dedicated to Allen Ginsberg, he considers the “Singh Durbar in flames” on 9 July 1973 as “Shiva’s justice rendered one week/ before the revoking of all hashish/ licenses in Nepal.” Cohen’s odyssey ended at the age of 76 in his native New York in 2011.

The other person about whom I knew little but was drawn to his amazing humanity, talent and poetic strength was Angus MacLise—‘the tall skinny one with the coathanger shoulders’—as described by Cohen in his poem. I could not have imagined how this freest of person could have worked within any system or discipline. But as part of being awed by media, I read a New York Times reprint of May 5, 2011 about this ‘Velvet underground person’ that quotes a musician’s remark—“Angus was one of the greatest drummers of all time and one of the greatest poets of all time.” I frequently visited Angus, and his wife Hetty and their small daughter in Swoyambhu. He gave me a collection of his poems entitled “The cloud doctrine”, which I now know was such a big name, thanks to easy media access. By reading Ira Cohen’s poem “Ballad of the Gone Mac Lise”, I knew he died in Kathmandu in 1979. I could not attend his funeral as I was away at Edinburgh University.

These were the characters I knew personally, and I feel overwhelmed each time I come across more media information about them. But out of perhaps dozens of such Nepal loving persons, two figures of the past dominate my mind. The first is the Japanese Obakuso Zen monk Ekai Kawaguchi who started visiting Nepal 116 years ago and about whom I wrote a book after researching in Japan and Nepal. The other is the nineteenth century resident diplomat Brian Hodgson, about whom I am reading a book by Charles Allen.

In conclusion, I would say it is always very productive to be awed by history as long as we know how creatively we understand its human side.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu