Opinion

Putting into practice

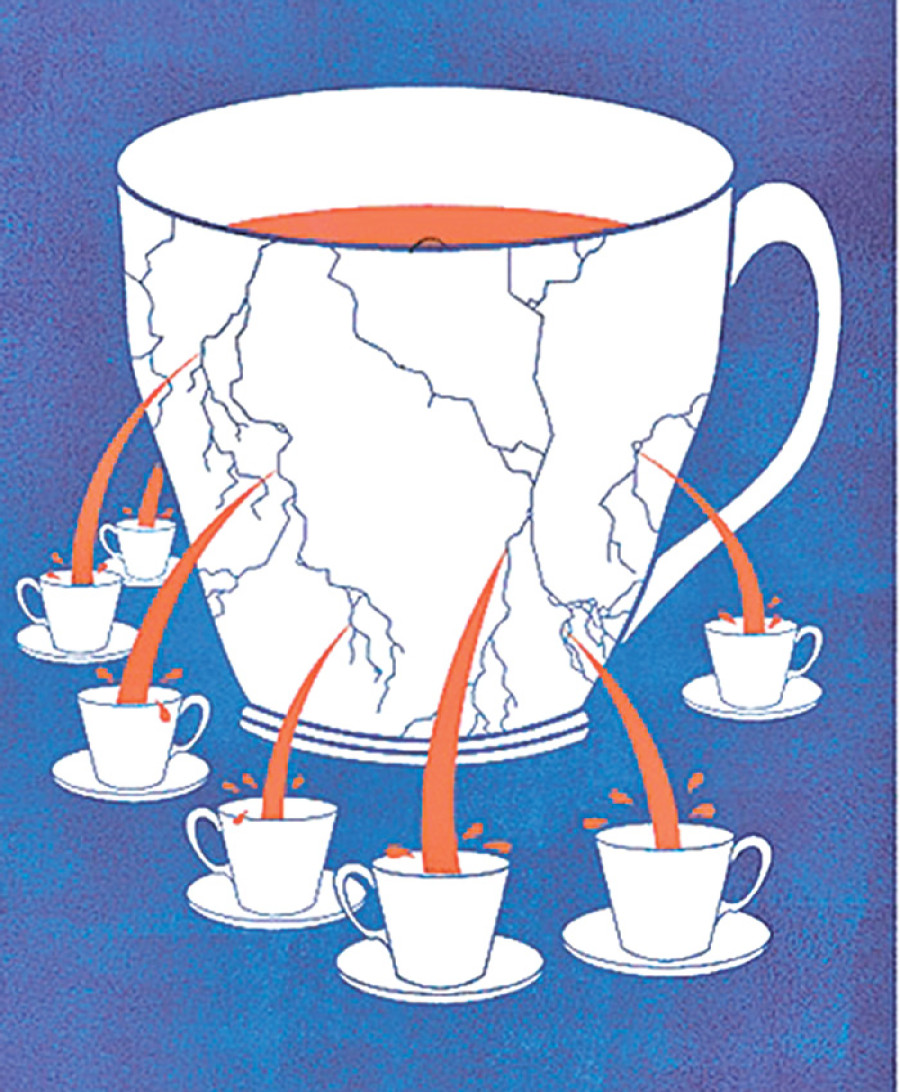

Disputes over federalism show that the people are still struggling to understand it

Yogendra P Paneru

The Maoists had raised the demand that a new constitution be written by an elected Constituent Assembly (CA) during the decade-long civil war. Last year, this demand was fulfilled with the promulgation of the Constitution of Nepal that guarantees democracy and federalism. Initially, federalism was just one of the issues raised during the insurgency, but it came into the limelight after the Madhes uprising in 2006. The ongoing controversies surrounding the constitution and the government’s inefficiency have raised doubts over the implementation of the document. This doubt has again drawn attention to the issue of empowering the political population with regard to executing federalism.

Confused federalism

The ongoing debates and controversies surrounding federalism indicate that the people are still struggling to understand it. Federalism is neither about organising a nation’s government, nor is it the means of dividing control among different components of a polity. Political parties should recognise that consociation, decentralisation, local democracy and democracy in general are required for the effective implementation of the constitution. These principles cannot be ignored because all of them share at least one additional feature with federalism. For instance, consociation grants authority and autonomy to subsidiary groups within the polity, decentralisation grants authority to geographically defined subunits, local democracy establishes political structures in geographically defined subunits, and democracy in general grants members of the polity defined rights against the central government.

Nevertheless, none of these benefits can be realised until the political institutions are fully prepared to implement federalism. Democracy is a system of governance, and democratisation is a process of delivering democracy and resolving conflicts through different means like accommodating the controversies that we are facing now. Having everything settled right after the first agreement is almost impossible, particularly in Nepal with such diverse ethnic populations.

Power-sharing necessary

Consociation has been practical in many countries that have transitioned from one kind of political system to another like South Africa, Cambodia and Ethiopia. Consociation, in the context of Nepal, can be considered to be the participation of all political and ethno-political institutions in the decision-making process, especially at the central level. While federalism in a democratic regime can be regarded as a form of consociation, the concept of consociation itself is much broader in terms of the institutions it covers and the mechanism it employs. So, if the political parties claim to be ideal federalists, they must comprehend that consociation is a desire rather than a choice because the instruments of our federal constitution are not yet developed. Advance coalition and power-sharing agrements are required between all political institutions.

It is obviously true that a strong opposition is a fundamental tenet of democracy. However, this fundamental principle will not function if democratic entities are not set up. Therefore, unless all the provincial governments are elected and state institutions are established, the idea of running majority and minority forms of government and Parliament is absolutely wrong. Political parties are both the parents and players of democracy, therefore, if they genuinely want to see federalism being implemented, each of them should be willing to participate in government and work together to develop a playing field where they can enjoy democratic freedoms without any fear. This is because the government and Parliament both need each other’s cooperation to deliver federalism successfully.

The government should work aggressively to provide work to Parliament by submitting bills and enforce the laws that are passed. Likewise, Parliament should be engaged in developing laws and evaluating the executive branches. The recently promulgated constitution is like an infant who requires intensive care by its parents. Hence, the decision by the Nepali Congress and the Madhesi and other ethno-political parties to stay in opposition and create a shadow government is worthless. The groups whose participation is invited and whose loyalty is secured in a consociative regime need not be geographically distinct. Each ethno-political group that has contributed to this political process deserves to be included in the consociation, and this is the right thing to do at this time.

Power-sharing unnecessary

Once federalism assumes full shape, implementing a consociational approach to governance is often unrelated because inclusive democracy itself is consociation, and the constitution has respected inclusiveness regardless of the complaints raised by ethno-political groups. In a democratic regime, power-sharing consists of four elements. First, the practice of proportional representation in the legislature enables all significant segments of the population to elect at least some members of their community. If the election results do not permit the formation of a majority government, the provision of ‘coalition government’ allows leaders from these segments to participate in executive decisions. Similarly, the requirement of a ‘concurred majority’ grants all segments the power of veto over legislative or executive decisions, and judicial review protects these arrangements from being undermined by a powerful majority.

The unifying theme around these mechanisms is that they allow minority groups to participate in the decision-making process of the central government. They are designed to ensure that minority voices will be heard in the national legislature and the executive, and that these bodies will not take actions that are unfriendly to minority interests. Therefore, they are often considered to be the polar opposite of federalism, in that they protect minorities by granting them a role in the

central government, and not by granting them a separate government apart from the centre with semi-autonomous authority. As of now, this reality has not been recognised by our political institutions, and they have been struggling for years to resolve this conflict. They assume that it can be resolved only by having a provision in the constitution to form separate governments apart from the federal government. This seems to be mathematically impossible at this time.

Paneru is a faculty member at Strayer University, the US

9.12°C Kathmandu

9.12°C Kathmandu