Opinion

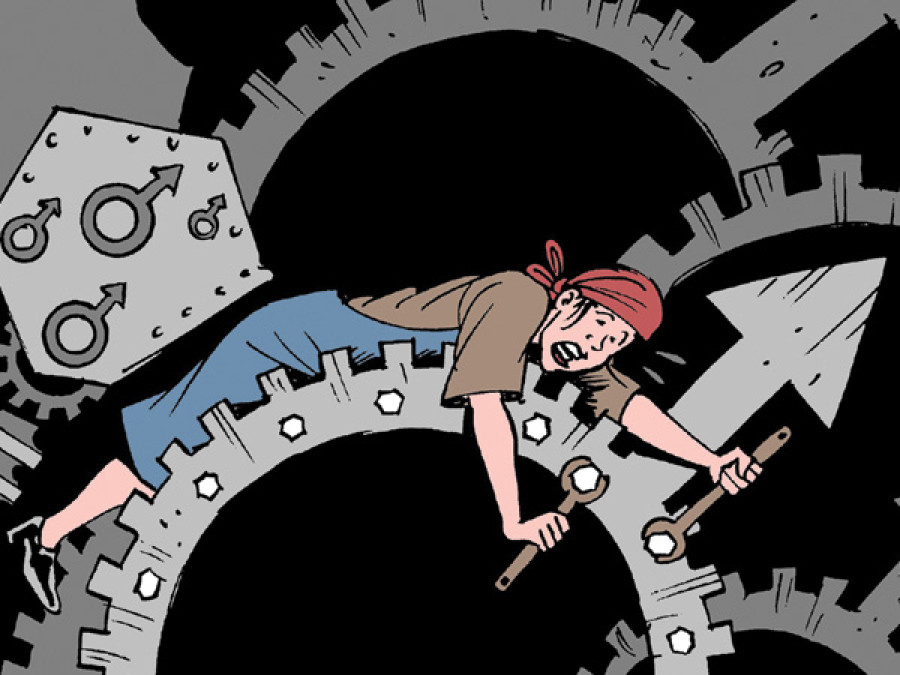

Invisible work

With changing gender relations, unpaid care work should now be given the attention it deserves

Anjam Singh

Women’s economic empowerment has been a much talked about issue both by feminists and development actors globally and in Nepal. However, much of the thinking and action have so far been focused on enhancing women’s participation and addressing discrimination in the labour force. The issue of unpaid care work remains largely unrecognised and its significance to women’s economic empowerment remains undervalued. Lack of serious consideration from the state, private sector and family continues to adversely impact the lives of many women who juggle between paid work and unpaid care work.

Conceptualising the term

‘Unpaid care work’ is a term recently coined by gender and development activists worldwide to reach a common understanding on the issue. Unpaid care includes activities such as cooking, cleaning and collecting fuel; care for people such as small children or older people; and other intra-household or community work. With its inclusion as one of the targets of gender equality in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it seems to be finally gaining some recognition.

The issue is not entirely new in the women’s empowerment discourse of Nepal. Meena Acharya and Lynn Bennett in their seminal work ‘The Status of Women in Nepal’ published in 1983 highlighted the concern about women’s domestic work burden and invisibility of their work.

But unpaid care work never got as much attention as it deserved in Nepal’s development practice.

Ironically, women’s unpaid care work has remained a non-issue not only in the state and private employment programmes but also in women’s economic empowerment programmes of the country. A majority of the economic empowerment programmes focus on involving women in small-scale income generating activities with the assumption that women’s access to economic resource would change their intra-household gender relations. In the absence of measures to address women’s household care workload, most of these economic empowerment programmes unintentionally contribute to additional work burden for women. Futhermore, the increasing rate of male labour migration from most of the rural areas has also burdened women, many of whom have to single-handedly manage all the unpaid care activities. Therefore, recognising women’s workload and supporting them have become even more relevant.

The impacts

Unpaid care work not only impacts women’s participation but also the nature of participation in the labour force. Gender norms that determine care work as women’s primary responsibility—associated with mobility restrictions in many communities—prevent women from fully participating in the workforce and limit them to low paying and informal work with intermittent working hours.

Women’s lack of education is often cited as the reason for their involvement in low paying informal jobs. However, lack of education has linkages with unpaid care work as many girl children do not go to or drop out of school to support care work at home.

The challenges to balance paid work and unpaid care work is not only prevalent among rural women with low income informal jobs but also in formal jobs in urban areas. Many urban women struggle to find a balance between highly demanding paid jobs and domestic responsibilities. In many instances, women quit their jobs or take up flexible employment after marriage or childbirth because of increased care work responsibilities as daughter-in-laws or mothers.

Similarly, discriminatory gender norms and practices are entrenched in the state and market structures. Women, especially during pregnancy and immediately after childbirth, are often seen as liability at workplaces. Maternity and especially paternity leaves are a recent phenomenon but with little support at home and lack of childcare and relevant facilities at the workplace, a lot of times women choose to leave the labour market or take up part-time jobs.

Recognise, reduce, redistribute

The discussion on the issue of unpaid care work has so far been conveniently ignored at family and state levels because gender norms still predominantly dictate our family lives and beyond; women have also been accepting and internalising it as their primary responsibility because it is not even seen as “work”; and, perhaps most importantly, because it requires a shifting of responsibilities and demands that families, workplaces and the state work harder. However, with the changing nature of intra- and extra-household gender relations and women’s increasing participation in the public sphere, it is high time the issue of unpaid care work was given the attention it deserves.

In this regard, three Rs—recognise, reduce and redistribute—have been popularised by the Gender and Development Network, a UK-based network that works on gender, development and women’s rights issues, to address unpaid care work burden.

The first R envisages ‘recognition’ by family, community and the state—recognition that women have been investing a large portion of their life in caring for the family; that the drudgery has severe impact on women’s physical and mental health; and that disproportionate distribution of unpaid care work responsibilities is unfair to women.

The reduction and redistribution component highlight the need to share the care workload by family, community and the state. Instead of glorifying women’s ‘superwomen’ avatar, the least families could do is promote a culture of sharing workload between women and men as well as girls and boys. Similarly, the community and the state also have a role to play to reduce the care workload through the provisions of public services, infrastructure and social protection.

It is important to understand that recognising, reducing and redistributing care workload are not a privilege given to women but a way of leveling the playing field for women who enter the labour force with a baggage. Only when women are given equitable opportunities and provisions will they be able to thrive as economically empowered citizens.

Singh is a research consultant for Institute of Social Studies Trust, a New-Delhi based non-profit organisation

18.95°C Kathmandu

18.95°C Kathmandu