Opinion

Let’s fix it

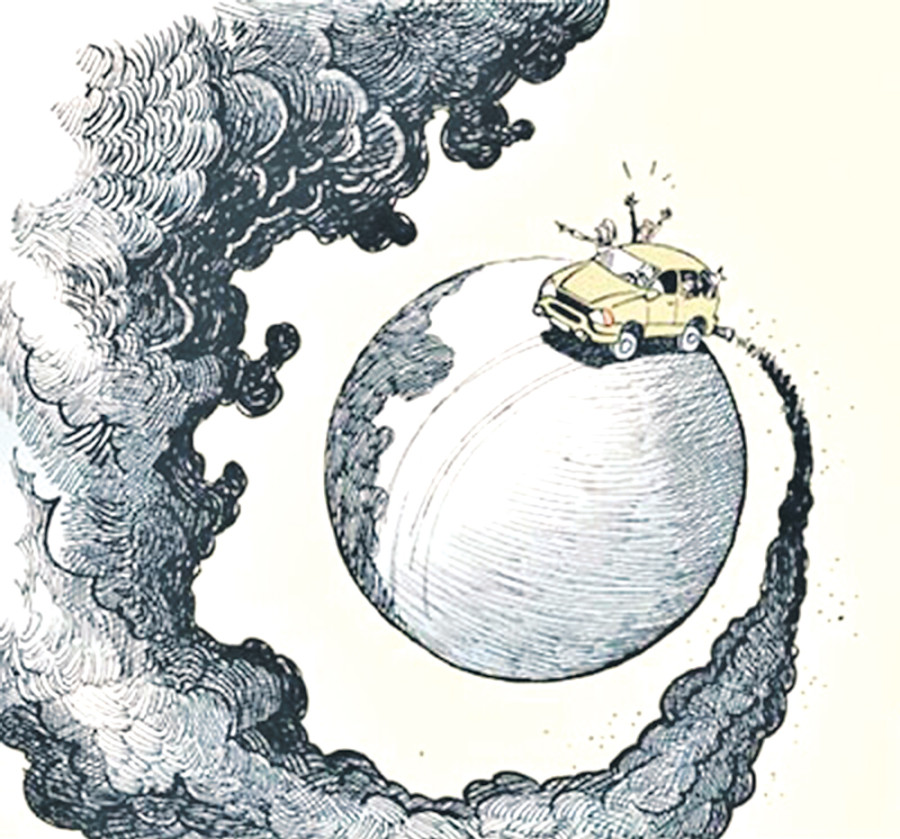

We need to understand our biophysical sensitivity and take timely actions to address environmental problems

Uttam Babu Shrestha

Air, food, water and shelter are the fundamental requisites for human existence. Even with rapid advancements in biology, medicine and technology, we have not found substitutes for these essential elements. Thus, deterioration in the quality of air, water and food systems diminishes the quality of life and ultimately pushes human civilisation to the verge of collapse.

Jared Diamond, a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of many bestsellers including ‘Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed’, had predicted Nepal to be on the brink of collapse while speaking at TED Talks in 2008. He painted a grim picture for Nepal and his propositions might have been exaggerated. But his argument was based on his extensive research of pre-historical societies, impacts of climate change, water management problems, over-exploitation of nature resources, encroachment of invasive species and the presence of hostile neighbours. Ancient societies failed mostly because they did not realise their vulnerabilities and their responses to the threats they faced were weak and late.

Diamond’s predictions seem pertinent, as the quantity and quality of essential components of life have been rapidly worsening in Nepal. The vulnerabilities of our infrastructures and shelters were exposed by the Gorkha earthquake. News reporting on air quality, water shortage and food contamination throughout the country depict the inferior conditions of these indispensable resources.

Geologically, Nepal is located in a very earthquake-prone area. The havoc created by the earthquake last year demonstrates that our shelters and infrastructures are lying on top of a time bomb.

Alarming statistics

Our mountains and hills are threatened by global warming and scientists have warned that climate change-induced floods, droughts, and landslides are expected to increase in frequency in the Himalayan region. Our region is warming faster than the global average and will likely warm up to 4-5 degree Celsius (2 degrees average) by 2050.

Our responses to inherent biophysical vulnerabilities are flimsy. Nepal ranks poorly in the 2016’s Environmental Performa-nce Index (EPI), a report card of countries’ performance on high-priority environmental issues such as protection of human health and ecosystems. Nepal ranks at 149th out of 180 countries on EPI. In terms of air quality only, it is the fourth most polluted country. Likewise, World Health Organisation (WHO) has placed Nepal in the ‘unhealthy for sensitive people’ category based on its air quality.

Reports on water are upsetting too. Water continues to be scarce in many parts of the country although water availability in Nepal is more than 8,000 cubic meters per person per year. Two years ago, water scarcity prompted entire residents of Samzong village in Mustang to move to a new location. It was perhaps the first forced migration caused by water scarcity in the country’s recent history. It is not unlikely that Nepal will witness similar incidents in coming years.

Recent reports on food, particularly farm produce, are equally scary. More than 15 percent of the fruits and vegetables sold in Kalimati contain high levels of pesticide residue harmful to human health. The pesticide residue found in potato, cauliflower, chilli and capsicum is three times higher than the level recommended by the WHO.

Problems of air pollution and water shortage are now common in all the major cities of the country. Kathmandu is the poster child for water scarcity and air pollution, while Bagmati is the most polluted river system. Other cities and river systems around the country are also following similar paths. Rivers and streams are being used as dumping sites by newly formed municipalities; major cities across the country are facing water shortages. Yet, the government and the general public have still not acknowledged the crisis. It is imperative for people to realise that although we cannot change our geography, we can make efforts at keeping our air clean, improving water management and regulating the use of pesticides in crops.

Past lessons and future directions

The Bagmati cleaning campaign, led by the former chief-secretary Lila Mani Paudel, is now running in its 150th week with some successful outcomes. The resources and efforts poured into the campaign show how difficult it is to bring a natural system back to its previous stage once it is spoiled. Therefore, we need to learn from our ignorance, transgressions and inactions, and manage our remaining resources sustainably.

We need to realise that we have created these problems; we have to understand our biophysical sensitivity and take timely actions. Strict enforcement of laws on environmental protection and resource conservation is essential. Historically, Nepal has tackled the problem of deforestation. In the early 1970s, when deforestation was widespread in the county, western scholars had echoed warnings similar to Diamond’s. We changed our policy, formed institutions, involved locals, garnered foreign aid and initiated a community forestry programme to address deforestation. Now, our bare hills are covered in lush green vegetation.

Shrestha is an environmental scientist

8.85°C Kathmandu

8.85°C Kathmandu