Opinion

Decoding identities

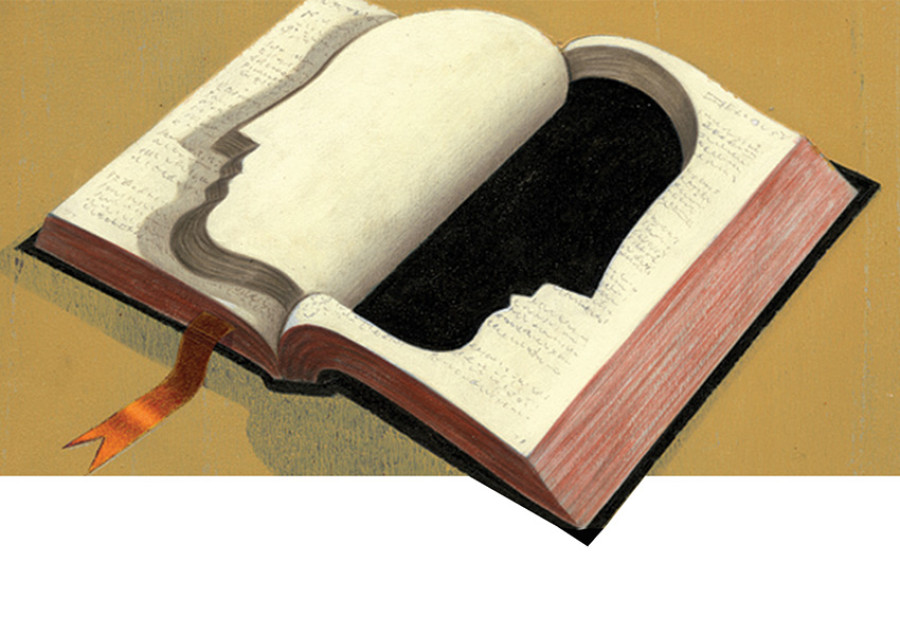

The projection of Nepalis in oppositional categories is a partial depiction of reality

Gaurab Kc & Pranab Kharel

Anthropology as a discipline that studies the ‘other’ has been a crucial academic engagement in Nepal. The discipline, which has a colonial legacy, is now operating in a new avatar and has established itself as a popular discipline among Nepalis and foreigners interested in academic pursuit here. The discipline has been important in shaping many of the discourses around the issue of identity in Nepal especially through Western ethnographies. One example of this is the construction of simplistic identities—especially along oppositional categories like Janajati vs Parbate Bahun/Chhetri.

One as another

Many ethnographic studies, especially those done by Western scholars, have tended to focus on such constructions. This article is not an attempt to argue that that these categories do not exist. However, what is missing in the discourse is the relational category these identities form. For instance, a Brahmin today would be different from one three generations ago. The intermingling of different ethnicities and the formation of a subsequent identity is what needs to be looked at. An exclusive focus on a single group would be insufficient to comprehend the discourse. A Brahmin today would not only cross the communal rules of dining but, importantly, undermine the marriage restriction imposed by the caste hierarchy, especially in the light of new wealth and prestige acquired through remittance. Therefore, the sight of a Brahmin consuming alcohol or entering into a marriage with a so-called lower caste group has become common, at least in the urban areas, if we wish to look at Nepali society’s urban-rural dichotomy.

Furthermore, a Brahmin participating in the marriage of a Limbu in Eastern Nepal whereby the former may participate in the cultural practice of carrying alcohol or a piglet as required in the marriage procession also portrays the cultural acculturation among the different identity groups there.

According to anthropologist James F Fisher, Tamangs who engage in the trekking business as guides like to identify themselves as Sherpas since the latter are renowned for their mountaineering skills. Fisher terms the process ‘Sherpaisation’. Therefore, the argument that only the practices of the upper caste is emulated by others needs a critical examination.

Fisher in the article titled ‘Reification and Plasticity in Nepalese Ethnicity’ published in the book Ethnicity and Federalisation in Nepal, has focused mainly on anthropology, especially ethnography. He cautions anthropologists against dividing people instead of uniting them in the federal setup. He also recommends doing away with ethnographic maps as he points out that “the conventional and long-held anthropological understanding of ethnicity as consisting of clear-cut, bounded, easily identifiable cultural groups (everywhere, not just Nepal) is grounded in fundamental error.”

Pahad-Madhes dichotomy

Much of anthropology in Nepal has focused on hill cultural groups giving little space to the developments in the Tarai/Madhes. Commenting on this tendency of her fellow communitarians, Canadian anthropologist Mary Des Chene argues that anthropologists have unintentionally tended to project the “hills, the in-between region, as the really Nepali part of the country.’’ What has followed is the belief that Nepali studies are exclusively focused on the hills. However, there has been increased attention to the area down south recently, which is largely the result of the political churning of 2007 which established Madhes as a dominant political constituency in the aftermath of the uprising.

In adopting such an approach, there seems to be too much focus on how the Madhesis are distinct from the Pahades. Migration has been a norm in every society, and it is used for political purposes, like in Nepal. But the intermixing of different groups has resulted in cultural formations such as speaking a common language. Maithili, Bhojpuri, Awadhi and Nepali, for example, are spoken by both the Pahades and Madhesis.

The formation of culture and the sharing of its traits is often associated with territoriality. In fact, territory contributes to identity formation in a substantive way. For instance, Pahades have also been celebrating festivals such as Chhath Puja and have adopted it as part of their culture. The missing analysis in the Madhes/Pahad dichotomy, however, is the failure to distinguish between the policies of the state, which are unquestionably influenced by a section of Pahades, and the cultural exchange between these two communities on the ground.

Change in outlook

Most anthropological writings in Nepal have tended to focus on the paradoxes among

different groups. This, although important, makes the narrative incomplete as relations among communities are not just shaped by oppositional forces. Everyday lived experiences are shaped by cooperation and not just assimilation. Nepalis are not as different and distinct as is being objectified in ethnographies. To quote Fisher again, “…they are all citizens of the nation and carry the same passports and are subject to national laws, but they also remember that they are ultimately not just Bahuns or Janajatis or Dalits or Madhesis, but that they are all also daju/bhai and didi/bahini.”

What makes it interesting is that the projection of communities as always in flux and in opposition to one another ensures the need to maintain stability. This results in a careerist approach of many seeking to understand the ‘other’. The late Nepali anthropologist Saubhagya Shah argued that the more Nepal sinks into chaos, the more it becomes the place to be for ‘democratic missionaries’. Therefore, the projection of Nepalis in oppositional categories is not just a partial reality of society but it also hampers the growth of anthropology as a discipline as it gives a one-dimensional approach to the methodology of the study and associated discourses.

Kharel and KC are affiliated with the Kathmandu School of Law

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu