Opinion

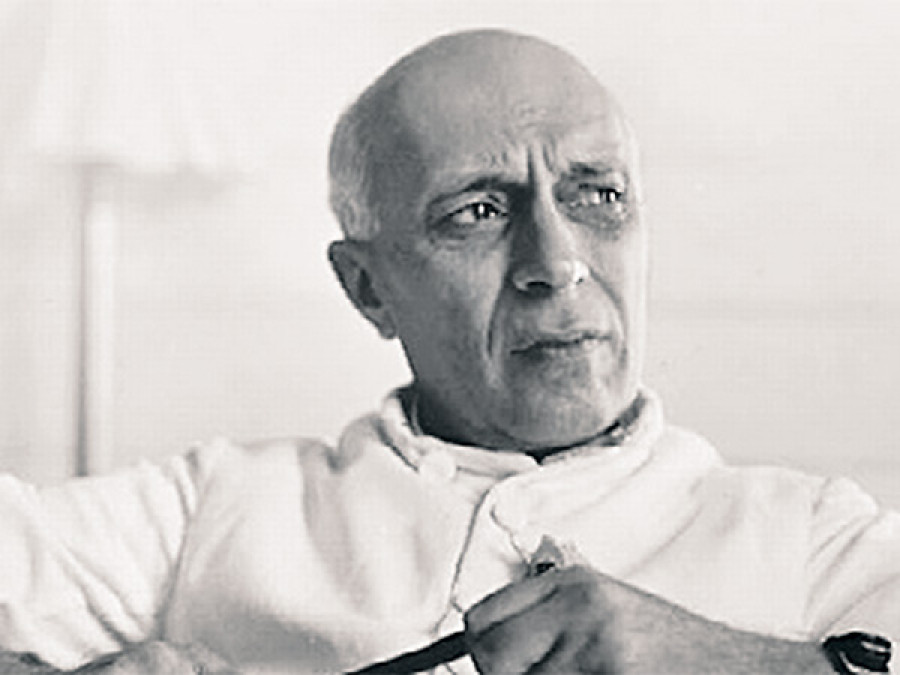

Nehru in New India

Nehru’s example can provide lessons for nations attempting to consolidate democracy.

Atul K Thakur

With a new regime in place in New Delhi, it is time for the past to be seen through the lens of the changed official wisdom. Consequently, a Gandhi, Bose, or Patel are in the mainframe—as to intentionally confuse them as ‘apolitical icons’ but with strong nationalistic fervour. Nehru, being the mover and shaker of the Indian Congress, receives no such cushioned treatment. But it doesn’t really matter as he was also a freedom fighter who spent years in jail to free India from its colonial shackles.

Nehru and Bose

Nevertheless, individually, few scholars have the vision to present history in a proper light and that continues for good reason. Rudranghsu Mukherjee’s Nehru & Bose: Parallel Lives is thus a remarkable entry in a thoroughly eventful 2014. It puts forward queries long suppressed: “Nobody has done more harm to me ... than Jawaharlal Nehru,” wrote Subhas Chandra Bose in 1939. Had relations between the two great nationalist leaders soured to the extent that Bose had begun to view Nehru as his enemy?

With the support of facts, Mukherjee argues here in precision. He dwells further, “But then, why did he name one of the regiments of the Indian National Army after Jawaharlal? And what prompted Nehru to weep when he heard of Bose’s untimely death in 1945, and to recount soon after, ‘I used to treat him as my younger brother’?”

Mukherjee covers both leaders individually and in comparison—against the backdrop of India’s epoch-making independence movement. This book brings both well into the light the riveting story of two contrasting personalities who would go on to define modern India. The good thing is the flawless narrative that allows the truth to prevail.

Nehru’s letters

Another important work that solemnly unleashes the many facets of India’s first prime minister and incorrigible democrat is Letters for a Nation from Jawaharlal Nehru, edited by Madhav Khoshla. Through the compiled letters, Khoshla, the young editor of this book, has supplemented a major work to look back on the works of Nehru for envisioning a modern India.

Starting way back in October 1947, two months after Nehru became independent India’s first prime minister, he wrote the first of his customary fortnightly letters to the heads of the country’s provincial governments—a tradition that he kept going until his last letter in December 1963, only a few months before he passed away.

Meticulously drawn from nearly 400 such letters from archives, this collection covers a range of themes and subjects, including citizenship, war and peace, law and order, national planning and development, governance and corruption, and India’s place in the world. Moreover, the letters also cover some crucial world events and the many crises the country faced with its nascent independence.

Remarkably written and intended, these letters are testimony to Nehru’s statesmanship and his deep commitment to India’s democratic journey. Leaving politics and errors of human judgment apart, Nehru’s commitment to democracy was unwavering and set a firm legacy, not just for India but for all of South Asia.

This book also has contemporary relevance for the kind of guidance it provides for current issues facing the Indian democracy. With the rise of single-party dominance and the weakening of the Congress party, a section of the intelligentsia is hell bent on rewriting history to reorient the future course of the nation. This ploy is far too dangerous to be overlooked.

Not just an Indian leader

The basic reckoning should be among those tempting souls that ‘testament’ has to be kept in order before ushering in a stream of history. Sans the free voice and greater stake of drama, even the world’s largest democracy will see vulnerable times, where the finest tenets of democracy would be buried under the great show of tamasha. For clarification, this apprehension is for the tendency to disrupt the spent time, and not meant to distinguish such tendencies based on ideologies.

The political parties can do the politics of history and this is quite worrisome, knowing how fragile the core constituencies of democracy are. This case is not India-specific. Nepal has its own share of fragility in the new pattern of identity politics that keeps at bay meaningful goals. This is not bad if it will not allow its dark underbelly to emerge too sharply and disrupt the prolonged quest to attain a basic democratic framework.

Nehru in today’s time needs to be seen more as a universal democrat than only the leader of one nation. Those harbouring the parliamentary form of democracy can hardly have doubts on his unwavering commitment. Better if this man were given the respect he deserves, irrespective of how the official colour changes in New Delhi every five years. Wishfully, this basic courtesy should be sustained, to help democracy and its intricate principles and practices.

Thakur is a New Delhi-based journalist and writer

6.12°C Kathmandu

6.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)