National

Yak and chauri farmers struggle amidst border restrictions

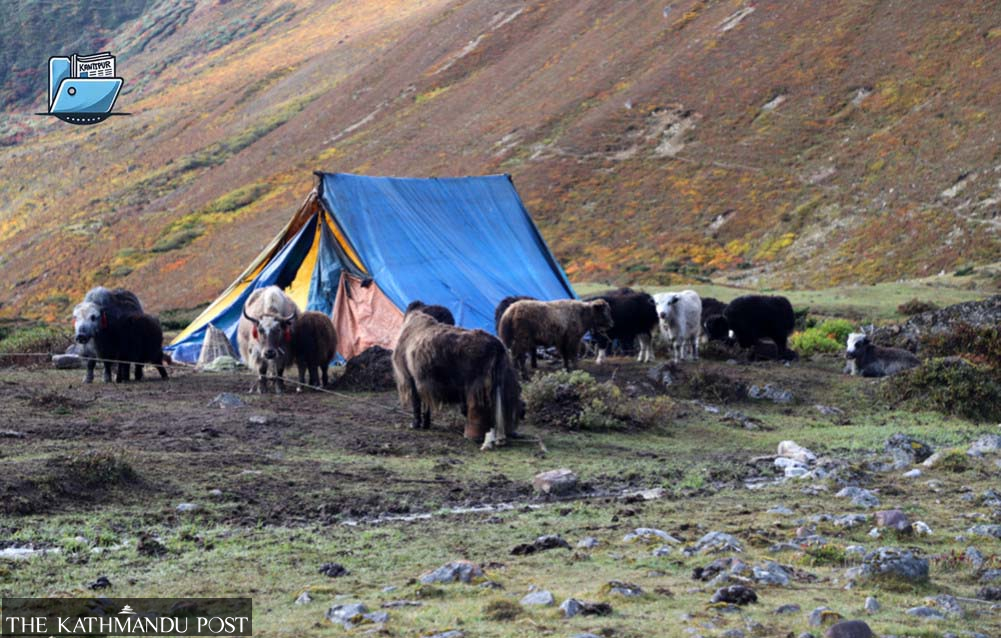

With trade routes to China still closed for livestock, hundreds of Himalayan herders are burdened by unsold yaks and chauri, facing financial uncertainty and mounting losses.

Ananda Gautam / DB Budha

Once a symbol of prestige and prosperity in the eastern Himalayas, yaks and chauri (Yak crossbreeds with local cows) are now becoming a growing burden for farmers. In districts like Taplejung, what used to be a thriving pastoral economy is teetering under the weight of closed borders, stalled trade, and overstocked herds.

For herders like Nupu Sherpa, who keeps 95 animals in the high pastures of Mikwakhola Rural Municipality, the challenges are escalating. “We used to raise yaks and chauri with pride — they were in high demand in Tibet and Sikkim,” he said. “Now, we don’t know how to feed them, let alone sell them.”

Sherpa, who inherited the profession from his ancestors, says he hasn’t earned a rupee from livestock sales in four years. Each year, around 25 to 30 calves are born in his herd, while 15 to 20 animals die due to age, disease, or wild animal attacks. “We raised them to sell once they matured, but now we’re stuck.”

.jpg)

Closed gates, open woes

Although border points like Tipta La in Taplejung and Kimathanka in Sankhuwasabha formally reopened in May 2024 after Covid-era closures, livestock trade remains banned. The restriction has disproportionately impacted yak and chauri farmers who rely on cross-border sales to earn income and control herd sizes.

According to Nupu Sherpa, the animals were traditionally sold to buyers from Tibet and Sikkim for meat, dairy, and breeding purposes. “Tibetan herders even used to come looking for improved Nepali breeds,” he recalls.

The Chinese market, with its larger economy and population, provided a steady source of income. Now, with that channel sealed, over 8,000 yaks and chauri in Taplejung alone are unsold and overcrowding highland pastures.

Farmers have had to lease grazing grounds at high costs — often paying between Rs25,000 and Rs60,000 annually to local landlords. In places like Papung in Mikwakhola-5, some herders are managing herds of up to 250 animals without being able to offload even one.

In 2023, the situation worsened with the spread of lumpy skin disease, which claimed over 60 of Chungdak Sherpa’s animals in Papung. Although the disease is under control now, the lack of trade options means his economic troubles persist.

Financial freeze in the highlands

The livestock service office of Taplejung confirms that about 60 percent of the 8,000 yaks and chauri in the district are ready for sale. The total estimated value is over Rs400 million. “If even 5,000 animals could be sold, it would breathe new life into these communities,” said one official.

The problem isn’t limited to Taplejung. Farmers across Panchthar, Sankhuwasabha, Solukhumbu, Tehrathum and Ilam are facing similar woes. In Guphapokhari, a tri-district junction, herders regularly gather to discuss one question: when will the Chinese market reopen?

According to Yak Chauri Farmers' Federation Nepal, around 180 families are fully dependent on yak and chauri herding in Taplejung. More than 300 additional households rear smaller numbers. “We are surviving, but just barely,” said Nupu.

Calls for government intervention

Despite repeated appeals, little has been done to formally negotiate a solution. During a border meeting with Chinese officials in Dinggye county in December 2024, Taplejung's chief district officer Netra Prasad Sharma raised the issue of livestock trade. Chinese representatives responded that the ban was a central government directive, citing quarantine concerns.

Phaktalung-7 ward chair Chheten Sherpa, who was part of the delegation, said the Chinese side seemed open to dialogue but non-committal. “They told us animals could only be traded after fulfilling quarantine requirements, but those facilities don’t exist on our side,” he explained. “This is where the federal government must step in.”

Sherpa also warned that without action, rising herd numbers will soon outstrip the carrying capacity of local pastures. “It’s not just about selling — it’s about survival now,” he said.

.jpg)

A brighter picture in Jumla

While eastern herders grapple with uncertainty, the mood in Chotra village of Jumla’s Guthichaur Rural Municipality is notably more hopeful. With 90 chauri under his care, Sangbu Gurung has managed to keep his traditional livelihood viable. Every three years, he sells 30 to 35 chauri, often fetching up to Rs65,000 per animal.

Gurung also produces ghee and chhurpi (hardened cheese) from the milk, which adds another layer of income. Traders from as far as Manang and even China visit the village to buy his animals.

In neighbouring households, such as that of Tondu Gurung, the sight of over 100 chauri grazing in the misty highlands is common. “From education to healthcare to festivals — everything is funded by chauri,” he said.

There are 64 households in Chotra, each rearing anywhere from 10 to over 100 chauri. With support from the local livestock service office, the community is slowly transforming into a yak and chauri pocket area.

Last week, 40 new animals — 37 chauri and 3 yaks — were distributed among farmers under a provincial programme that combines government and community investment. “With Rs30 lakh already invested, we aim to make Chotra a model village for yak and chauri farming,” said livestock official Gyanendra Singh Budhthapa.

The way forward

As herders across the Himalayas wait for clarity, time is not on their side. Overcrowded pastures, expensive fodder, and a closed trade route have left the region in limbo.

District Coordination Committee, Jumla’s chair Gaurinanda Acharya believes that developing places like Chotra into yak-breeding centres could help alleviate some of the pressure. “We must turn crisis into opportunity,” he said.

But for herders in Taplejung, relief can only come if the livestock trade with China is officially resumed.

Until then, their prized animals remain trapped in highland pastures — unsold, unfed, and slowly turning from a source of pride into a burden too heavy to bear.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu