National

A rape survivor’s account shows how society and state fail those who report crimes

Many survivors have their lives uprooted, are forced to relocate, live away from their family and friends, and start fresh in an unfamiliar setting.

Tsering Dolker Gurung

She tried to tell her friends several times. But whenever she mustered up the courage to share what had happened, she would instantly remember his words: “Don’t tell anyone, or else...”

The first time he raped her was on the day of her cousin’s wedding. She was alone in the house, getting ready to join the rest of her family at the ceremony, when a man walked into the flat and locked the doors.

The man was in his 30s, a carpenter who had been hired to work at her uncle’s home. She was only 13, an eighth grader.

“Don’t tell anyone or else…,” he warned her.

The girl, now 14, who asked to be identified as Pabitra, doesn’t remember how many times she was raped, her memory is murky. She has compartmentalised the trauma.

Pabitra’s story is not unique. In Nepal, a majority of rape victims are girls like her — minors in their early teens.

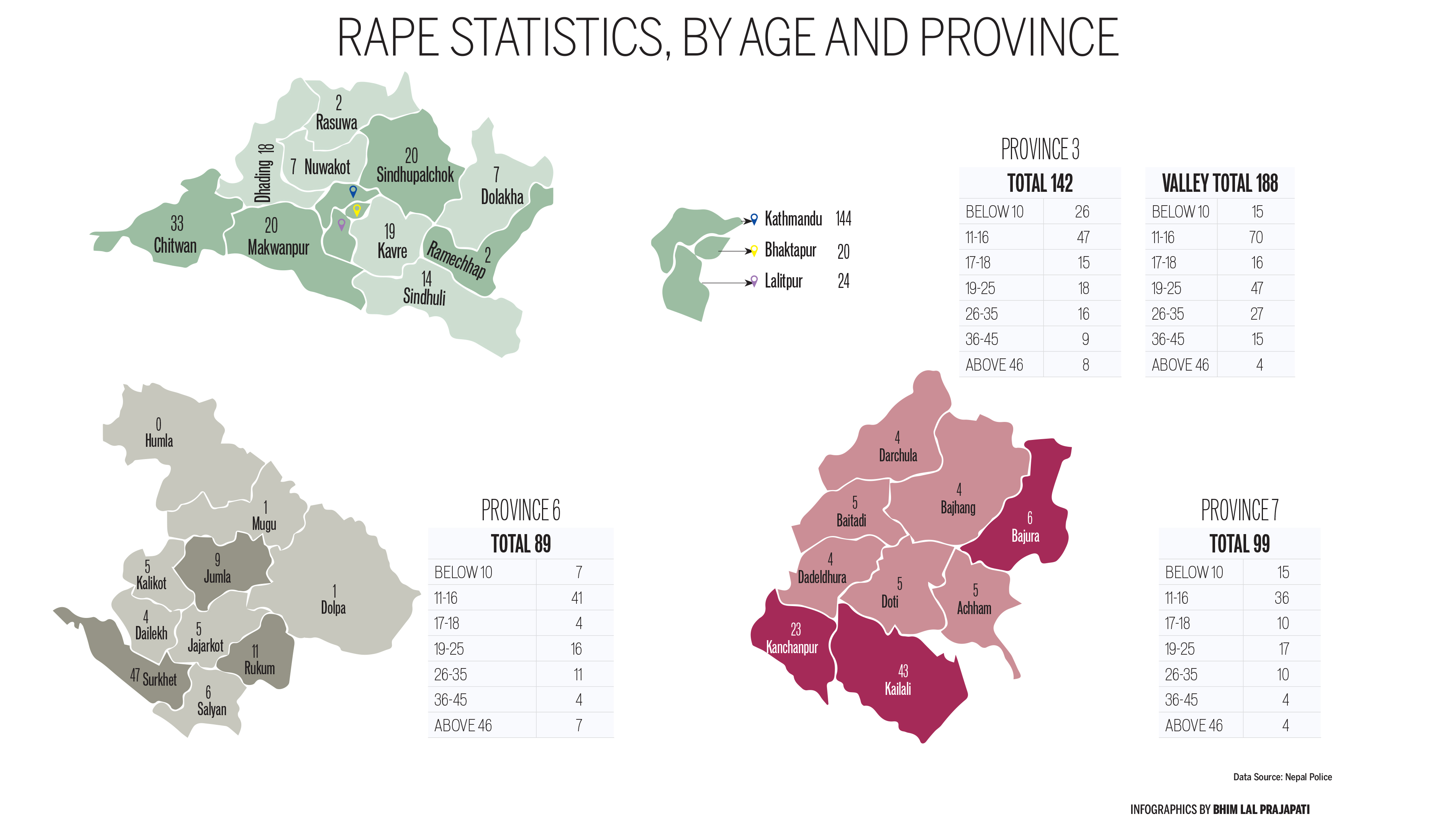

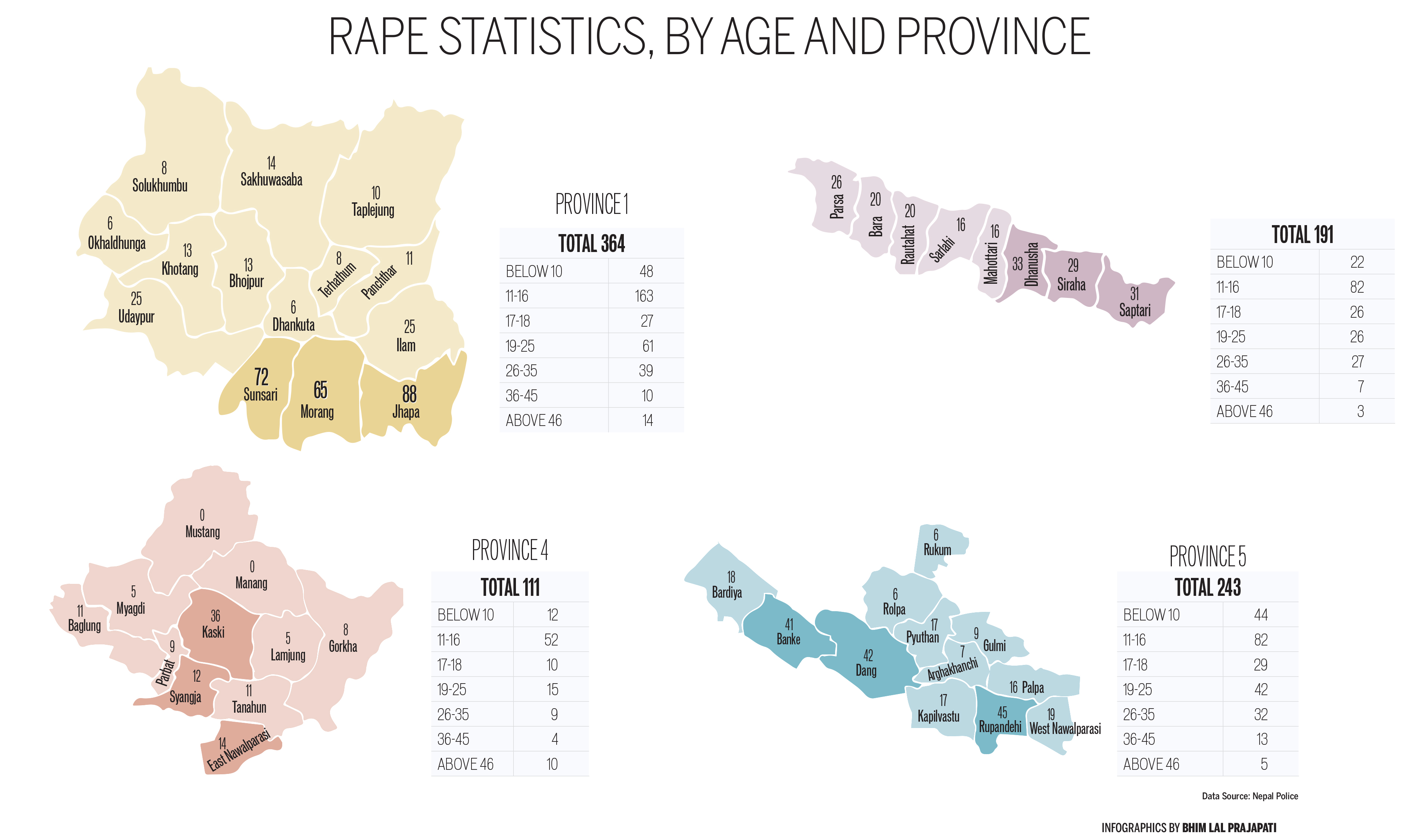

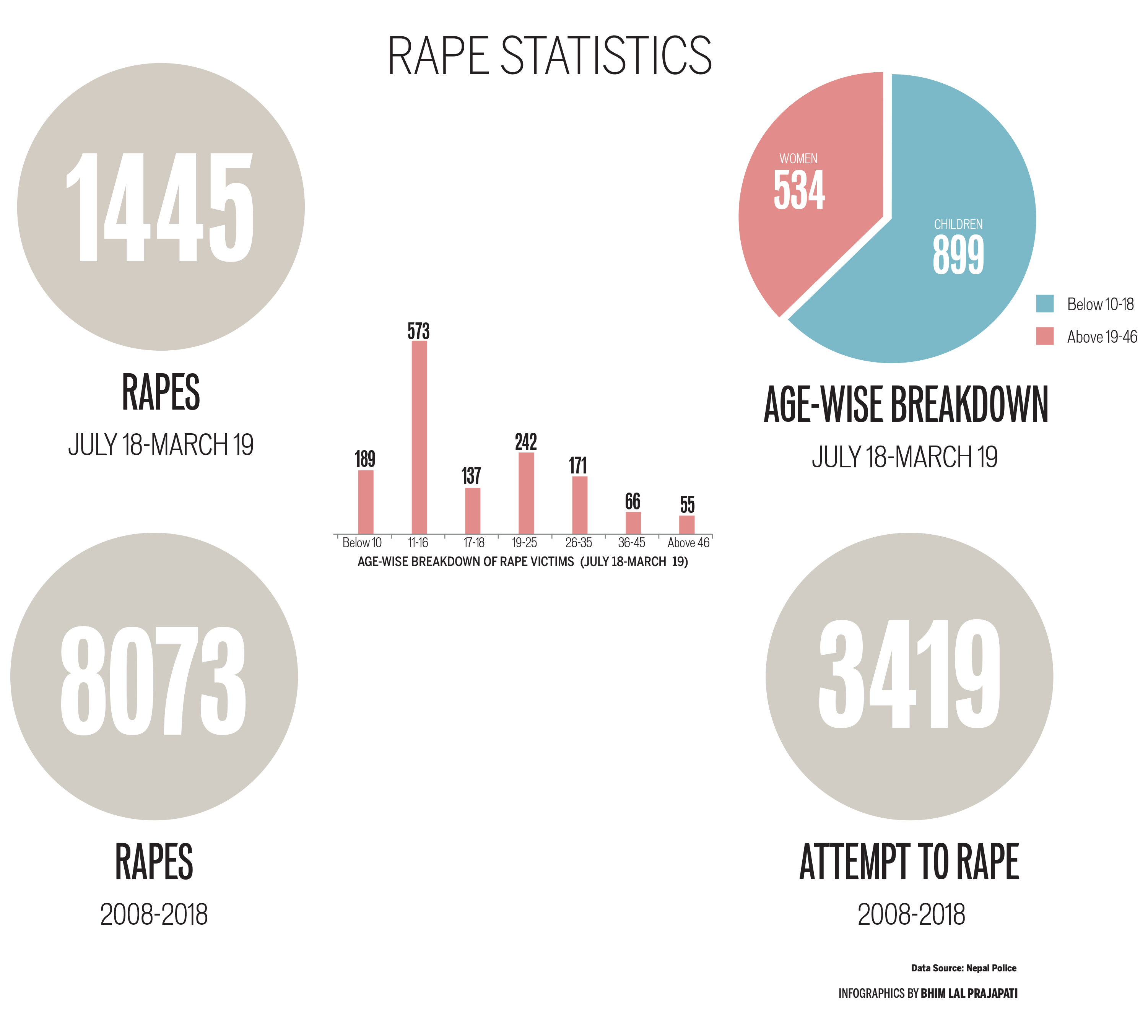

An age-wise breakdown of police data on rape crimes show that a majority of victims are young girls under the age of 18. Over 1,400 incidents of rape were reported to the police between just July 2018 and March 2019. More than 60 percent of the victims were minors.

And most rapists, according to police, are like her assailant — people familiar to the victim, family members and close family friends — which makes it more difficult for victims to report incidents. For rape victims like Pabitra, this puts them in a double-bind, where they are unable to speak out, not just because they are children but also because of the influence the rapists exercise on the victims and their families.

Pabitra remembers her rapist, the man who worked upstairs at her uncles’s, who everyone thought was a decent person. She wanted to tell her mother, badly, but was never able to conjure up the sentences to describe what had happened.

She missed her period three months after she was first raped. She had hoped that the health worker would run a pregnancy test and somehow infer that she had been raped. Instead, she was simply told she was dehydrated. No tests were performed. No questions were asked.

Five months later, she returned to the same clinic after falling ill. This time, she was attended to by a different health worker. He touched her belly but didn’t say much. She returned home with some medication.

Overnight, news that she was pregnant spread across the village like wildfire. Seemingly everyone learned about her pregnancy before she and her family were informed. The very next day, some volunteers from a local organisation showed up at her home, wanting to know what had happened.

Nearly nine months after she was first raped, the 13-year-old was finally able to tell her story. She spoke to the volunteers and her family filed a complaint at the police station. The man was arrested.

Her perpetrator is now in police custody, awaiting trial. Somehow, Pabitra, who’s been staying at a shelter in Kathmandu for the past two months, feels imprisoned too.

***

In January this year, a district judge in Myagdi sentenced a 53-year-old man to 41 years in prison after finding him guilty of raping his 12-year-old daughter. He was given 25 years for the crime of incest and 16 years for rape.

That same month, another man in Butwal was arrested for raping his 10-year-old daughter. The girl had been raped multiple times by her father. She was able to tell her mother only a month after the abuse began.

“In a lot of rape cases involving young girls, the protector is the perpetrator,” Raj Kumar Koirala, Myagdi’s district judge, told the Post in April.

Authorities say many victims of sexual violence choose to remain silent for a specific few reasons: fear of reprisal, fear of societal backlash, fear of being stigmatised, and fear that they won’t be believed. Families, according to the police, choose not to report rape incidents in order to protect the family name.

“We have also found that families try to hide evidence and choose to side with the perpetrator and not the victim when the perpetrator is someone from within the family,” said Shesh Narayan Bharti, chief of the Women and Children’s division at the Butwal District Police.

In a lot of cases, like Pabitra’s, stories of rape only emerge after a victim is found to be pregnant.

A mother in Sindhupalchok learnt that her husband had been raping their 14-year-old daughter, three years later, only after she got pregnant. The mother then filed a complaint, the police arrested him, and the court sentenced him to 15 years in jail.

Similarly, a 12-year-old girl in Jhapa, who had been raped multiple times over the course of a year by her neighbour, was only able to tell her parents after they found out she was pregnant. The rapist is now in police custody, awaiting trial.

As in the case of Pabitra, both these girls now live in safe homes. Their families do not want to keep them at home due to fear of being ostracised.

“There’s still a lot of stigma and shame attached to rape,” said Gita Adhikari, deputy mayor of Damak Municipality in Jhapa, a district with one of the highest numbers of reported rape incidents. “Till today, there are many parents who believe it is better to get their daughters married off to their rapists than seek justice through the court system.”

An analysis of 20-year police data on rape crimes shows the number of reported incidents has been rising rapidly each year. A majority of these cases are marked as “solved” in police records, meaning the perpetrator has been arrested. But only a half of them result in a conviction at the courts.

Lapses in police investigation and delays in medical examination, sole emphasis on physical evidence by judges, and external pressure to change testimonies all contribute to a low conviction rate, lawyers overseeing rape cases told the Post.

The police’s mishandling of the investigation into the rape and murder of teenager Nirmala Panta last July brought to light just how easily police can tamper— intentionally or unintentionally—with evidence and corrupt a crime scene.

“We have good rape laws but the people responsible for enforcing the law often fail at their jobs,” said Punyashila Dawadi Ghimire, a lawyer who has represented many victims of sexual violence.

Families of rape survivors complain that the police are often too slow to respond— arriving late to the crime scene, taking days to start an investigation, and filing charge sheets only after repeated pressure from victim’s families.

Last August, Reshma Kumal of Jhapa was searching for her eight-year-old granddaughter when she saw their neighbour, a 68-year-old man, lying down in their chicken coop. When she took a closer look, she saw her granddaughter was under him. She screamed, and the man fled.

According to Reshma, the incident took place at 3 in the afternoon, but the police only showed up at night.

“When we called the police asking why they hadn’t come yet, they said they didn’t have any vehicles to commute to our village,” said Reshma.

“The police only works on behalf of those families who can exert influence and pressure,” said her daughter, Manita Kumal. “In our case too, the police were very slow in filing the charge sheet. It was only after a local activist spoke out about this issue during a public meeting that they filed the charges.”

According to the Kumal family, the eight-year-old’s medical check up was also delayed.

“We went to the hospital the day of the incident itself, but were told by the doctor to come back the next day,” said Manita.

In an interview with the Post, Mahendra Shrestha, deputy superintendent of the Jhapa District Police, dismissed allegations that his office is lax at investigating rape.

“We take rape very seriously,” said Shrestha. “Once the case comes to us, there’s no compromise on the investigation.”

According to Shrestha, investigations suffer primarily because of non-cooperation from the community, and the victim’s family reach out to the police only after the two parties can’t work out an arrangement.

“By then, it’s already too late to collect evidence and our investigation suffers,” said Shrestha.

Some advocates say victims tend to grow ‘hostile’ during case proceedings, changing their testimonies, owing to pressure from the perpetrator.

“If they say it didn’t happen in court, we can’t say it did,” said advocate Ram Sharma. “Until victims can freely share their stories without worrying about threats and fear, the number of incidents will keep increasing.”

Other advocates point towards judges’ emphasis on physical injuries as indicative of rape.

“Our judges think that victims should have physical marks and injuries proving she fought her rapist,” said Duwadi. “But if there’s no such evidence, then the judge tends to cast immediate doubt on the victim’s story.”

Additionally, Duwadi said, it is much tougher for adult victims who are already sexually active to prove to the court that she has been raped. Despite progressive changes in the definition of rape, many judges, according to Duwadi, still believe that for a rape to have happened, a woman’s hymen should be ruptured.

“A lot of genuine cases get thrown out because our judges still have not been able to change their mindset and do not clearly understand the concept of consent,” she said..

***

Days are long at the shelter. There is not much to do, except sit and stare, counting down the days to her due date.

Soon after Pabitra’s family found out she was pregnant, they brought her to the Paropakar Maternity and Women’s Hospital, a government-run facility in Kathmandu, to get an abortion. But it was too late, the doctors told them. She was 27 weeks pregnant and would have to carry the pregnancy to term.

“If only the health worker had done a pregnancy test when I first went to the clinic, this wouldn’t have happened,” Pabitra said, her hands placed over her pregnant belly.

She wanted to return home to Sindhupalchok, but her family told her it would be best for her to stay at the shelter in Kathmandu, away from the glaring eyes of villagers.

“They say people are still talking about me in the village,” she said.

Pabitra still speaks with them over the phone but always ends up crying after each conversation. The other girls and women at the shelter ask her what happened but she still can’t tell them.

Those living at the shelter are not allowed to speak to each other about their individual cases. It’s an internal policy, one that’s in place to maintain confidentiality, according to Samjhana KC, a social worker associated with the organisation running the safe home. For her, it’s a rule that doesn’t make much sense, only makes the days longer to while away.

Seeing other children leave for school each morning makes her miss having a normal life. The daily ritual of waking up at a certain time, putting on a school uniform, walking to school with friends, making fun of the English-language teacher who did not speak any English—all of these, Pabitra said, feels like in the distant past.

“I want to study at least until grade 12 and become a teacher,” she said.

When, or if, she completes high school, she wants to teach social studies at her village school, where she was a student until only a few months ago. Now, she is not sure if she’ll ever be able to return home.

***

Calls for justice for rape victims primarily centre around the arrest and prosecution of perpetrators. For survivors though, their agony doesn’t end with a judge’s decision to convict a perpetrator.

Many of them have their entire lives uprooted; they are forced to relocate, live away from their family and friends, and start fresh in unfamiliar settings.

A 14-year-old girl from Sindhupalchowk who reported being raped by her father is now living in a shelter because her mother told her she couldn’t take care of her financially. Her sisters also blame her for sending their father to jail and have told her not to return home.

“I miss my mother, I miss her very much,” the girl said, breaking down. “I want to go home but I can’t. My family doesn’t want me and the villagers talk about me.”

In many cases, the only place left for these girls are safe homes and shelters run by government and non-government organisations.

“When we don’t provide immediate care and protection to victims of sexual violence, there’s a high chance they will be re-victimised,” said Adhikari, the deputy mayor of Damak, under whose initiative the municipality got its first safe home this year. “Local governments all across the country can do much more to protect their victims.”

The Kumal family in Jhapa was forced to send their granddaughter to live in Kathmandu because the villagers kept pestering the eight-year-old with questions about the incident.

In an interview with the Post, one mother of a four-year-old girl who had been raped by her 17-year-old cousin said she worries about the day her child will grow up, only to be reminded of the incident by others in the community.

“Right now, she has no idea what happened, so it hasn’t affected her,” the mother said, looking at her daughter, a young girl playing in the courtyard. “What will happen if someone asks her about it when she grows old enough to understand what rape means?”

***

Last week, at the maternity hospital in Kathmandu, Pabitra gave birth to a baby boy. As with most babies born out of rape, Pabitra’s child will be given up for adoption. She and her family have discussed this and consulted with the organisation that is currently looking after her.

Until the adoption is finalised, the baby will be staying at the shelter with her. She is curious to know what will happen to the baby.

“Ma’am,” Pabitra called out to the social worker one morning. “Will you let me know who will take care of my baby?"

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu