National

Family mourns, and a country recoils at teen girl’s rape and murder

Since the day Nirmala Pant's body was discovered, the parents' lives have been consumed by a fight to seek justice for their daughter. They have tirelessly protested, taken part in street demonstrations, reached out to administration officials and local leaders whom they believed might be able to help, and given numerous interviews to the media to make sure their daughter’s story is not forgotten. But Durga Devi, the mother, says she is beginning to feel all of their attempts may have been in vain.

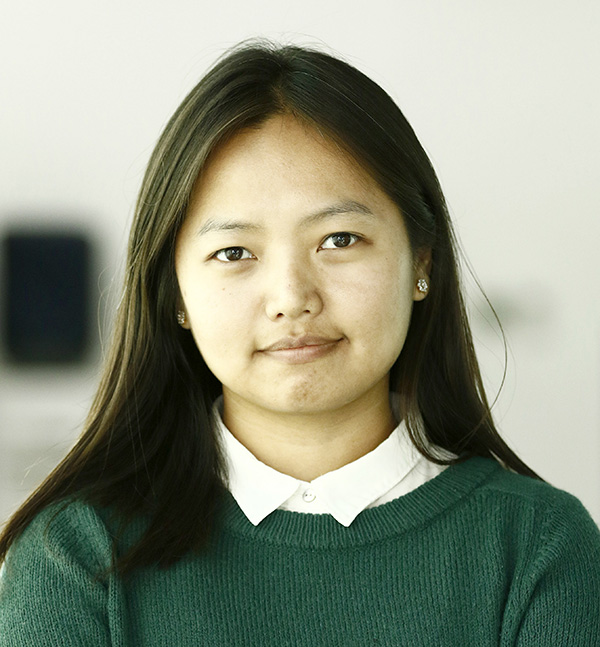

Tsering D Gurung

For several weeks now, Durga Devi Pant has been waking up each morning with one question on her mind: “Who killed my daughter?” The thought plagues her throughout the day and is the last thing on her mind as she struggles to sleep at night.

“Nirmala loved drawing,” said Durga Devi, staring at a sketch of Lord Krishna their 13-year old daughter had made only a few months ago. Now it’s one of the few remnants of her existence in the house.

The middle child of Durga Devi and Yagya Raj Pant, Nirmala Pant, was a soft-spoken and mild-mannered ninth grader. She was what many typically described as a “good” girl: respectful, responsible and ambitious.

Her dream, friends and family say, was to become a nurse. In case that didn’t work out, Nirmala wanted to become a teacher, Manisha, her elder sister, said. Barely into her teens, Nirmala seemed to possess a certain sensibility about life, usually present in people much older—and perhaps borne out of her experience watching her mother struggle to raise her and her sisters on her own after their father took in a second wife. Those close to Nirmala say she was determined to lift her family out of poverty so they could lead more comfortable lives.

All of their dreams took a tragic turn on the afternoon of July 26. Nirmala had left home late in the morning, Durga Devi said, to pick up a notebook from her friend. She never returned. After failing to find Nirmala at her friends’ house, Durga Devi filed a report with the police, who told her they’d look into the matter the next day.

The next day, Nirmala’s body was found in a sugarcane field—she’d been raped, strangled and murdered.

Since that day, the Pants’ lives have been consumed by a fight to seek justice for their daughter. They have tirelessly protested, taken part in street demonstrations, reached out to administration officials and local leaders whom they believed might be able to help, and given numerous interviews to the media to make sure their daughter’s story is not forgotten. But Durga Devi said she is beginning to feel all of their attempts may have been in vain.

“I held onto hope for so long,” said Durga Devi in an interview with the Post last week at her home in Bhimdutta. “When the new [investigation] team took charge, I was positive they’d uncover something. Now I am not so sure.”

Nearly two months after Nirmala’s lifeless body was discovered, law enforcement authorities have not made any progress with the investigation. Despite a nationwide protest and continuous calls over social media for the government to act, the probe into her killing took an abrupt turn after the police were forced to release their key suspect, Dilip Singh Bista, as medical reports showed his DNA did not match the sample obtained through vaginal swabs of the victim. Two other suspects, Roshani Bam and Babita Bam, whose house Nirmala had gone to collect her notebook the afternoon she disappeared, were also released on Wednesday; the police cited a lack of significant evidence against them.

What happened to Nirmala Pant is not an isolated incident. According to police reports, three new rape cases are reported across Nepal every day. This is a four-fold increase from a decade ago. The actual number of cases is estimated to be much higher, given that many victims do not come forward to file complaints. The police’s general attitude towards victims, a culture of victim-blaming, and lack of prosecution of such crimes, are all to blame, rights activists say.

“Because of societal norms, many girls and women still do not feel comfortable going to the authorities to report crimes of sexual violence,” said Mohna Ansari, a commissioner at the Nepal Human Rights Commission. Furthermore, she added, those responsible for investigating such crimes and ensuring justice to victims are themselves coloured “by a traditional mindset which makes them question the victims rather than the perpetrators.”

Last month, Nepal introduced a new criminal and civil code that increased the statutory limit to report rape from six months to a year and increased the maximum jail term for anyone convicted of rape from 15 to 20 years. But, activists say the problem isn’t so much the lack of laws as it is about implementing them.

What should be a simple task of registering a complaint can be an uphill battle, says Kanchanpur-based social activist Bhawaraj Ghimire. Through his experience campaigning for the rights of ordinary citizens, he says he has witnessed just how apathetic authorities are to victims of sexual violence, especially those who have neither wealth nor influence.

“Until and unless the police stop working on the basis of orders from the powerful, the common people will never trust them,” Ghimire said.

Across the country, there is also a general tendency among law enforcement officials to settle such cases outside the court of law. In many parts of Nepal, it’s not uncommon to see rape victims married off to their culprits.

Durga Devi Pant at her home in Bhimdutta Municipality in Kanchanpur. The Pants moved here from Kailali’s Lalpur over a decade ago. Photo by Tsering D Gurung / For The Kathmandu Post

When Durga Devi and Yagya Raj first moved to Bhimdutta Municipality from Kailali’s Lalpur over a decade ago, the couple had big plans. At the time, Durga Devi was pregnant with their third child, Saraswati, who is now 11.

Yagya Raj wanted to leave behind farming and set up a small shop in the market. He convinced Durga Devi it was their shot at achieving prosperity. So the couple sold their ancestral land and settled in Kanchanpur.

But things didn’t go as planned. Yagya Raj’s decision to bring in a second wife a year after they moved to Kanchanpur split the family. He moved to Bhasi, just a few kilometres away, with his new wife and set up a pani puri stall.

For somebody who rarely ventured outside her home and was largely dependent on her husband, it was a life-altering moment for Durga Devi, who found herself solely responsible for the upbringing of her three daughters.

To supplement their income from farming, Durga Devi set up a chatpatey stall in front of her house. The stall has remained shut since the day Nirmala was found dead.

“I just can’t bring myself to work,” said Durga Devi, who is constantly troubled by not knowing who her daughter’s killer is.

Her neighbours regularly drop in to check on her. They bring her vegetables, offer words of support, and assure her she’ll get justice.

But she is not so sure anymore.

Durga Devi said it was her daughters who gave her hope—and who became the reason she wanted to continue living the life she had.

“I had high hopes for my daughters,” she said. “I used to think they would have better lives than mine.”

Despite their separation, Durga Devi and Yagya Raj have maintained a cordial relationship and have been each other’s support as they continue to go through the tragedy of losing a daughter.

At the Saraswati Higher Secondary School, where Nirmala was a student, the mood is still sombre. Students and teachers continue to reel from the shock of what happened to one of their own.

“A lot of us are still in disbelief,” said headmaster Jagannath Pandey. “We could have never imagined something like this happening to one of our students.”

It’s been particularly hard for Nirmala’s classmates and friends, who are reminded of her every time they step into the classroom. Nirmala’s drawings line one side of the wall and are the first things a visitor notices when entering the room.

“For a month, we didn’t feel like studying at all,” said Laxmi Badu, one of Nirmala’s friends. “Even now it’s difficult to concentrate on our studies.”

Badu, who has known Nirmala since the fourth grade, remembers her as someone who was friendly with all students and had a great relationship with teachers. Nirmala, she recalled, preferred sitting on the front benches in class so she could pay more attention to teachers.

Nirmala’s teachers describe her as a “curious” child. Someone who was always eager to learn, not afraid to ask questions, and determined to do something with her life.

“She was more mature than other students her age,” said Tripti Bhandari, Nirmala’s ninth-grade teacher. “She seemed to understand the importance of education and worked hard in school.”

The “incident,” as most of the locals call it, still features heavily in conversations among students and teachers. Nearly a quarter of the school’s 350 students pass through the sugarcane field where Nirmala’s body was found on their way to school every day. This is traumatising, teachers said, especially because the culprit still has not been caught.

“Until the police find Nirmala’s killer, our students will not be able to walk around fearlessly,” said Pandey, the headmaster.

Teachers and students at Saraswati Secondary School are still in shock from what happened to one of their own students. Photo by Tsering D Gurung / For The Kathmandu Post

Earlier this week, the police released three suspects who had been held in custody since last month: Roshani Bam and Babita Bam, who are believed to be the last ones to have seen Nirmala alive; and Dilip Singh Bista, a middle-aged local resident whose arrest prompted mass protests in Kanchanpur, resulting in the death of one person after police fired live rounds to disperse the protesting crowd.

From the very beginning, Bista’s arrest was seen by many residents as an attempt to frame an innocent. Locals claimed Bista was mentally ill, incapable of committing such a crime, and more importantly, they argued, he was home when the incident took place. On Wednesday, three weeks after he was paraded around Bhimdutta Municipality, Dilip Singh Bista was finally released by Kanchanpur Police.

But even before the developments this week, the investigation into Nirmala’s murder has been marred by accusations of negligence, evidence tampering, and attempts to protect the real culprits at all cost.

Dilli Raj Bista, ex-Superintendent of Police in Kanchanpur, the highest-ranking law enforcement official in the district, was suspended after his team was accused of engaging in gross misconduct during their initial investigation. The unit was unresponsive to repeated requests from the family to start investigating their daughter’s disappearance and was reluctant to bring in the Bam sisters for questioning. Some locals were also wary about the police’s role and involvement in the crime because of its failure to seal the crime scene and its tampering with the evidence by washing the victim’s body and her clothes, according to those present at the scene.

“Initially, Dilli Raj Bista told us that Nirmala had been gang-raped,” said Meena Bhandari, coordinator of the Struggle Committee formed after Nirmala’s death. Bhandari said she grew suspicious after the police announced Dilip Singh as the primary suspect. When she questioned ex-SP Dilli Raj Bista about the discrepancy between his earlier claim and the arrest of Dilip Singh, she said he told her to shut up. “Either the culprit is so powerful that the police cannot reach him or they fear retribution from those involved,” Bhandari said.

SP Kuber Kadayat, who took over the investigation in August, said it is precisely these reasons why his team has collected blood samples from ex-SP Dilli Raj Bista, his son Kiran Bista, and Bhimdutta Municipality Mayor’s nephew Ayush Bista, and sent them to the laboratory for DNA tests. He said the results from the tests will answer a lot of questions and allay suspicions.

Local residents said Kiran, 19, and Ayush, 23, were friends with the Bam sisters and regularly visited them at their home. Nirmala’s parents believe the two were there on the day she went missing.

“We heard it was Kiran’s birthday that day,” said Durga Devi. “Maybe Nirmala was introduced to them that day.”

Durga Devi Pant holds a drawing of Lord Krishna made by her daughter, Nirmala Pant only a few months ago; (right) Durga Devi Pant with her other two daughters, Manisha, 15, and Saraswati, 11, at their home in Kanchanpur. Photo by Tsering D Gurung / For The Kathmandu Post

As the investigation fails to make any headway, skepticism about the police’s ability to solve the crime and bring the guilty to the book has turned into frustration.

The resignation earlier this week—and subsequent withdrawal—of Birendra KC, a member of a high-level probe committee formed to look into police conduct during Nirmala’s murder investigation, has raised more questions about whether powerful interests are trying to influence the investigation. During a press conference on Tuesday, KC told reporters he faced threats to his and his family’s lives and said he did not believe the committee was capable of bringing justice to Nirmala’s family.

But in a shocking turn of events, KC withdrew his resignation a day later, saying he believed it would be better for him to continue working with the committee, after a meeting with Home Minister Ram Bahadur Thapa.

In addition to finding the culprits, activist Meena Bhandari wants action against the Central Investigation Bureau and police officials who were involved in destroying evidence and manipulating the investigation, officers responsible for the illegal detention and torture of innocent civilians, and those responsible for the death of a young protester.

“The state should think about the human rights of every citizen, not just of the rich and powerful,” Bhandari said.

Hemanti Bhatta, 17, a local resident, said she was repeatedly harassed by the police under SP Dilli Raj Bista.

The high school student told the Post she was brought in for questioning on four separate occasions. She was repeatedly told by the police to confess to the crime or else be tortured. They questioned her for six hours straight, she said.

“They’d say admit you are guilty or we’ll splash hot water on you,” said Bhatta, who still doesn’t know why she was specifically targeted. “I’d tell them why should I when I have nothing to do with Nirmala’s murder.”

On one occasion, she said the police officers hung her upside down and one officer hit her feet with a stick. She said she can’t tell who the officer was because they were dressed in civilian clothes.

“I was then told not to tell anybody outside about what they had done to me,” said Bhatta.

Timeline: A look at the Nirmala Pant rape and murder case

Tired of waiting for answers, Durga Devi and Yagya Raj travelled to Kathmandu on Wednesday to meet with top national leaders, including Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli.

“It’s unfortunate that in our country we have developed a culture where individuals seeking justice feel they need to approach political leaders rather than the police,” said Bhawaraj Ghimire, the Kanchanpur-based activist. “It speaks to the general mistrust of the public towards police.”

The death of Nirmala Pant and the Pant family’s ongoing ordeal has made Nepalis question if, in Nepal, justice is afforded to only the rich and powerful.

Many local activists point to the culture of offering impunity and protection to individuals with “connections,” something that is pervasive within the justice system and reflective of the way the country functions in general.

“The police should stop operating under the influence of power,” Ghimire said. “Until that happens, there will be many other Nirmalas.”

Even as Nirmala’s case grips the nation, new rape cases continue to make headlines. Earlier this week, a 10-year old girl was raped in Kanchanpur, Nirmala’s home district. This followed reports of a gang rape of a teenager in Illam, and then another one in Chitwan.

For rights campaigners, especially women, ensuring justice for Nirmala has become more than just about one person, said Meena Bhandari, who accompanied the Pant couple on their trip to Kathmandu.

On Thursday, a tearful Yagya Raj, Nirmala’s father, broke down as he addressed journalists at a press conference in Kathmandu.

“We demand justice for our daughter,” he said. “We demand that her real killer be prosecuted. And if the state can’t do that, then we ask the state to kill us, like you have killed our children.”

READ RELATED STORIES:

- Editorial: Police incompetence is turning the tragic Nirmala rape case into a farce

- Relatives refuse to receive the body of Nirmala Pant

- President Bidhya Devi Bhandari calls for justice to Nirmala

14.09°C Kathmandu

14.09°C Kathmandu