Movies

A tale of two wives

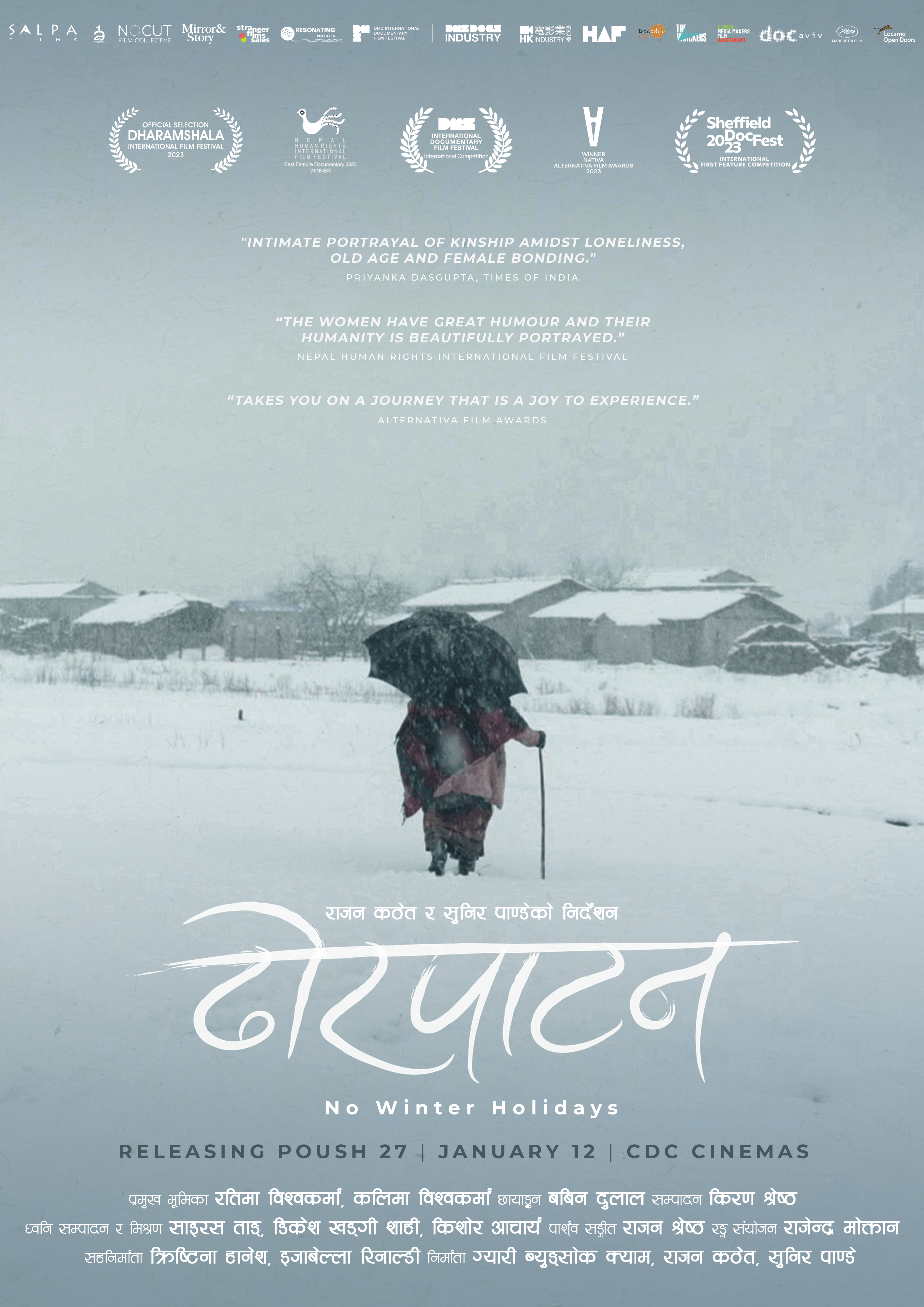

The documentary ‘No Winter Holidays’ is a sneak peek into the life, or lack thereof, in Dhorpatan as villagers migrate to the lowlands.

Deepali Shrestha

Before the days grow shorter, harvests start to decline and the ominous shadows of dark clouds foreshadowing snow and hardships envelop the skies of Dhorpatan, the villagers move down the valley to escape the atrocities of winter. They abandon their homes and fields under the watchfulness of the co-wives, Ratima and Kalima—the only ones prepared for the frigid days ahead.

The epitome of the phrase “show, don’t tell” is evident in Sunir Pandey and Rajan Kathet’s debut documentary film, ‘Dhorpatan (No Winter Holidays)’. This 79-minute feature-length documentary won the AlterNativa Film Awards 2023 for the ‘Nativa’ category and ‘Best Documentary’ at the Nepal Human Rights Film Festival. It depicts the story of two sautas, Ratima and Kalima, the only chaukinis guarding the settlement during Dhorpatan’s hostile winter.

Ratima, the older, childless wife, recounts her dream of her dead husband. He sometimes appears as a handsome young man, sometimes as a middle-aged man and then as an older man. Kalima, the second wife, also harbours dreams, not of their dead husband’s but of snakes, helicopters and flowers.

Ratima speaks less and sings more about her worries, sickness and memories of the good old days. She smokes cigarettes and drinks her sorrows away. The only companions in her life are her songs, alcohol and the memories of her late husband. When the camera shifts to Kalima, who is younger and more vigorous, the film’s melancholy mood becomes humorous.

Kalima awaits her daughter’s phone calls and keeps herself busy spending time with her beloved dog, cow and goats. She tries to communicate with her animals as if they can comprehend her witty remarks, which gives one a good laugh. The depiction of her materialistic side reminds me of how second wives, who usually get accidentally caught up in the family, are understood in our society. The stark difference between these two women facing similar circumstances of old age and isolation lucidly portrays how one cannot comprehend the gravity of their husband’s loss that the other feels.

From the exposition itself, it is evident that the film isn’t driven by a particular genre, conflict or character motivations but rather by mood. Empty places have a certain eeriness within themselves that exudes a feeling of what could have been there. The film’s first few minutes, with the shots of the locked doors, empty fields and lonesome hills, is almost like a foreboding of something dark about to be revealed.

Clearly, the makers have been very patient in filming the story, as the film’s slow pace and the emphasis on the characters’ monotonous activities are essential for an immersive experience. The recurring long shots of the landscape are like watching a season pass, and my memory has still retained some shots, which feel like postcards from Dhorpatan I’ve received from the makers.

The tension between co-wives brings dynamics to the film. Sauta has interesting connotations in Nepali as they are generally viewed as rival wives, resembling oil and water. We witness their bonding in the first half, but their relationship gradually turns bitter. The filmmakers aren’t in a hurry to show their tussle for the drama, which makes it more natural and believable. Although they become spiteful of each other and exchange harsh words, they are aware of their shared predicament. Later, in a scene where Ratima’s health worsens, we see Kalima beside her in the dark room, looking after her.

As a documentary maker, it becomes your utmost responsibility to make the characters comfortable. I remember the phrase “characters bring soul to your documentary” from my film class. In the film, we progressively witness the true nature of the co-wives unravel as they become comfortable with the makers. Kathet and Pandey have delicately captured the rawness of Ratima and Kalima’s relationship, making us connect with them as first-hand witnesses of their everyday lives. ‘Dhorpatan’ doesn’t reaffirm the stereotypes about sauta in our society, nor does it try to contradict them. It is a film about two co-wives negotiating the terms of engagement in a landscape that demands companionship for survival.

I am a sucker for good music and take music choices in films seriously. And the background score by Rajan Shrestha (Phatcowlee) didn’t disappoint. The eerie music of the first few minutes—akin to horror films—immediately sets the atmosphere of ‘Dhorpatan’. Even if you enter the cinemas in high spirits, the ominous music makes you feel terribly sombre. The lonesome, snow-covered landscape and the hardships blend well with the music, conveying that there is no escape from the place or their budheshkal (old age).

As the winter ends, the music becomes hopeful, symbolising the return of warmer days. The village springs to life with children running around, women lining up for water and men walking around with their cycles. Spring and its warmth become evident in the faces of Ratima and Kalima. A different side of their characters emanates when they are with the locals who respect them for their roles and seniority. I couldn't help but wonder how it might have been if this part was shown before winter. Perhaps the makers opted out of that to set the mood straight from the beginning, or maybe not. As an audience, I can only speculate. Only when the background score reaches a crescendo, indicating the approaching winter, does the directors' choice make sense.

The film’s storytelling could have been better. I respect the makers’ choice of focusing on the feels and world-building more than the narrative, which still works. However, as the film’s universal theme revolves around women, their relationships and oldage, more dimensions of the storytelling could have been explored, making it more complete.

For the sake of satisfying film enthusiasts interested in knowing the film’s style, it is safe to say that ‘Dhorpatan’ could be a “fly-on-the-wall documentary”. In essence, it is a film that offers an anthropological lens into the lives of the people adapting themselves to nature’s complexities. Seasonal migration is a way of life for many Nepalis to survive and diversify their livelihood. ‘Dhorpatan’ gives us a glimpse of what the change of seasons means to a community, especially older people and how they sustain their livelihood in compliance with nature’s law.

In countries like Nepal, where people still hesitate to take money out of their pockets to watch nuanced fiction films like ‘Ainaa Jhyalko Putali’ and ‘Paani Photo’, it is a considerable challenge for documentary makers to attract common people to watch their films in cinemas and find their target audience. I am glad that Kathet and Pandey are among the rare bunch who took the risk. Documentaries mustn’t only be destined for film festivals and then eventually made to rest in the makers’ hard drives forever. Since these films are truth and fact-bound, we need to support them, as this is the only way such art forms can find their way to the common people.

Dhorpatan (No Winter Holidays)

Language: Nepali

Subtitles: English

Director: Rajan Kathet, Sunir Pandey

Released on: January 12, 2024

Now showing: CDC Cinemas

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu.jpg)