Movies

Snapshot of the times

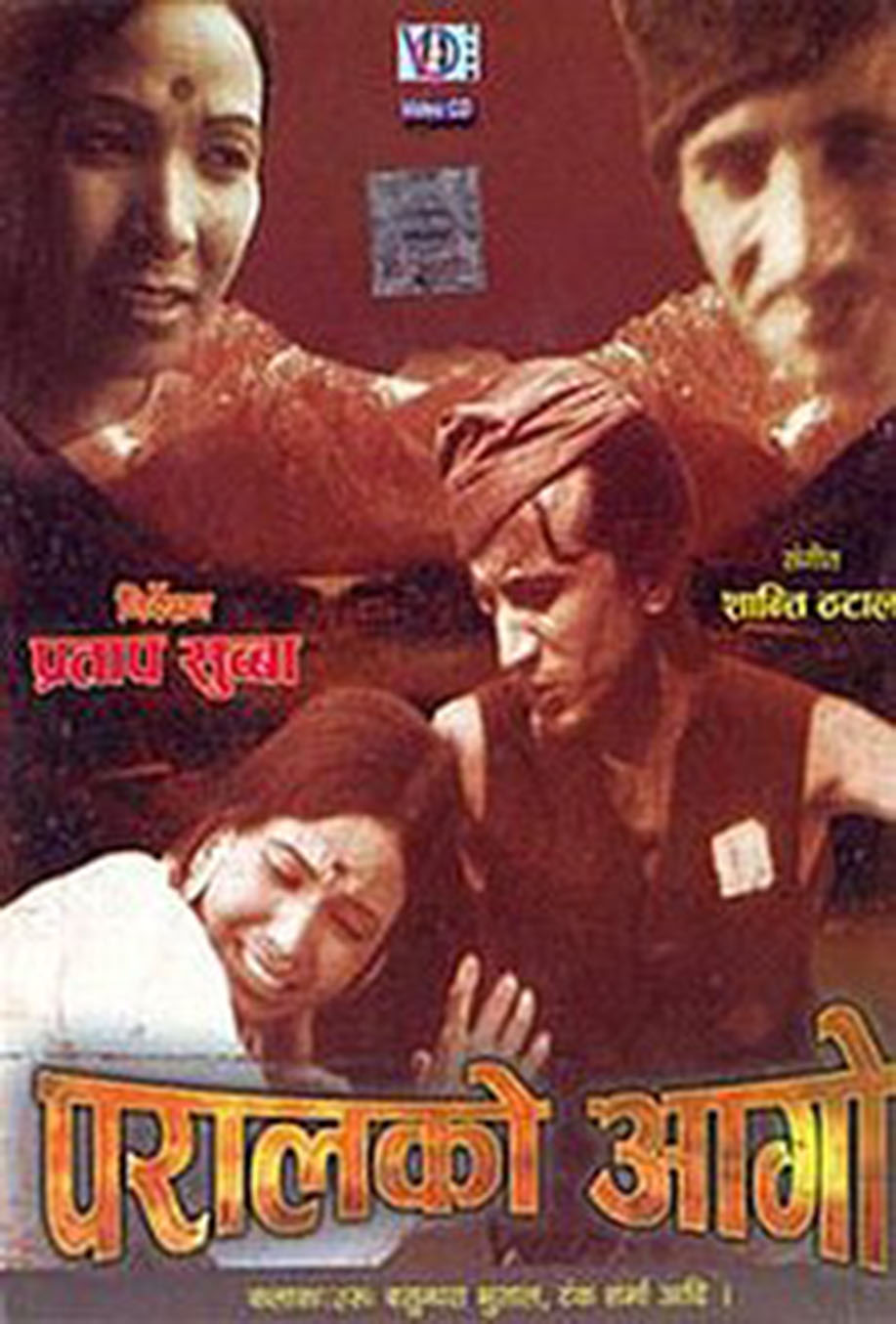

Famed director the late Pratap Subba’s iconic 1978 film ‘Paral ko Aago’ is brilliantly made but has a regressive plotline.

Urza Acharya

Yes, yes. Before anyone starts spewing the same old defense against critiquing films or literature from the past, I want to say—I know. Things were different back then. You can’t see the past with today’s moral standards. But should that always be the case?

This is what I had to keep on telling myself as I watched Pratap Subba’s 1978 film ‘Paral ko Aago’. Subba, a veteran filmmaker from Darjeeling, made several other films like ‘Bachna Chahane Haru’, ‘Masaal’, and ‘Kahi Adhyaro Kahi Ujjyalo’. He passed away on March 16.

Based on a short story by writer Guru Prasad Mainali of the same name (known as ‘A Blaze in the Straw’ in English), the story follows the lives of husband and wife, Chame and Gauthali. Mainali is a writer from the realism school of thought, or ‘yatharthabadh’ in Nepali. His other popular stories include Naso (The Ward) and Sahid (The Martyr). His stories are incredibly didactic—a little too much for my taste, but I understand where he’s coming from. During the early 1900s, perhaps writers felt like it was necessary for stories to have a moral message—don’t discriminate, send your kids to school, and whatnot . And ‘Paral ko Aago’ has a similar social message: Don’t hit your wife. Well…you can hit her a little. But not so much that she leaves home.

Pratap Subba first read the story while studying in Darjeeling. In an interview, he claimed, “The story had driven me mad. The plot of the film circled my mind day and night. I had to make it. So I did.” Starring Tanka Sharma (an actor from Darjeeling) as Chame, and veteran actress Basundhara Bhusal as Gauthali, ‘Paral ko Aago’ is considered an archetype of Nepal’s early cinema. And it’s not difficult to see why.

As a film, ‘Paral ko Aago’ is brilliant. The adaptation of story to script is almost religious—even the dialogues are the same. For a black and white film made in the 1970s, the structure and editing of the film are seamless and much more sophisticated than that of contemporary Nepali films. The length is around one and a half hours and rarely does anything feel out of place. Except for a short montage of a jhakri (shaman) curing an ill person. That comes out of nowhere and I still can’t figure out why it was put in the film.

Despite being shot on film, the cinematography oozes through the screen. At the beginning of the film, we see Gauthali attending a wedding, with roaring panche bajas and dancing people. There’s also a very fun little dohori montage between the groom and the bride’s sides. The clear skies, small mud houses, cows grazing, and people in the village going about their day is an honest portrayal of the time (and perhaps relevant even today).

A secondary storyline also follows in the film, one of Juthe Damai (I don’t even want to begin dismantling how casteist that name is) and his wife. In contrast to the always bickering Chame and Gauthali, Juthe Damai and his wife are shown to be very understanding and loving. They act as mouthpieces for both Mainali and Subba to transfer moral messages to the audience. In one scene, (which is not present in the story) Juthe Damai, while sewing clothes for an ‘upper-caste’ villager, politely points out the irony of how people wear the clothes he makes but don’t drink the water he touches. Gauthali’s mother—who is non-existent in the original story—acts as a mouthpiece that defends Gauthali’s decision to go back to her maita (maternal home). She comforts a crying Gauthali saying, “It’s okay. We’ll plough our fields and work harder to keep you here. No need to go back to him only to be a slave.”

Subba gives Mainali’s story more nuance—giving the Dalit characters as well as the women in the film, a voice and in turn, more autonomy. Subba clearly had a vision for the film, and that’s why at least technically, it’s so sharply made.

The best part of the film, without a doubt, is the music. As she comes back with fodder for the cows, we hear Gauthali sing (her beautiful voice lent by Aruna Lama), “I would fly away, but I am no bird, I cannot bear to stay.” All the songs are so masterfully composed and sung, it’s impossible not to feel nostalgic for the musical brilliance of the aadhunik songs of the 1970s.

Yes, the plot of ‘Paral Ko Aago’ is casteist, misogynistic, and even normalises domestic violence. But you should watch it nonetheless. Because Mainali’s story and, in turn, Subba’s film are a reflection of the past—they speak from an era where issues of equality didn’t even exist. Still, Mainali, though in a flawed way, urges husbands to be kind to their wives (which should be a given). Similarly, in the film, Subba subtly points out the absurd and distorted narrative of untouchability.

I’m not a believer of revising history. Because no matter how cruel it was, there is always something to learn from and see how far we’ve come. So, as viewers of today, we have to watch ‘Paral ko Aago’ with a grain of salt. One thing we have to acknowledge and appreciate is Subba’s vision, the film’s historical significance as well as its technical mastery (given the resources). But for the story…it’s a sign of the times.

Paral ko Aago

Language: Nepali

Subtitle: Not available

Duration: 1 hour, 31 minutes

Director: Pratap Subba

Cast: Basundhara Bhushal, Tanka Sharma and Menuka Pradhan

Released: 1978

9.21°C Kathmandu

9.21°C Kathmandu