Movies

Washing down pain with some raksi

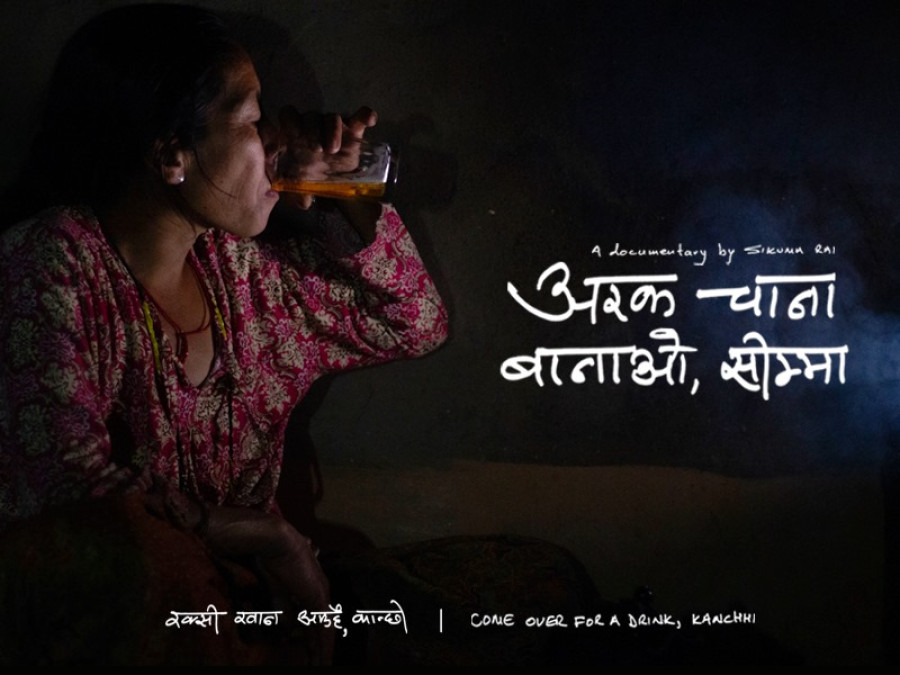

Sikuma Rai’s latest documentary ‘Come over for a drink, Kanchhi’ is an earnest and empathetic attempt to tell the stories of women for whom alcohol is a friend in trying times.

Ankit Khadgi

There’s a sense of uneasiness I feel whenever there is a discourse around alcohol consumption. Growing up in a Newa family, alcohol has always been an integral part of my culture and traditions. The same goes for many other indigenous culture groups, where consuming alcohol isn’t only normal but also a cultural tool that ties the community to their rituals.

However, the overarching narrative when it comes to alcohol consumption is very different. Dominant cultural groups have never made drinking alcohol a part of their culture and thus it is often looked at in bad light. And while there’s no denying that regularly consuming alcohol can lead to alcoholism, for many indigenous people, drinking is not only part of their culture but one that is revered and rejoiced.

Bringing such a story about how alcohol is deeply embedded in the Kiranti culture, filmmaker Sikuma Rai’s latest documentary ‘Come over for a drink, Kanchhi’ is an earnest story that dwells on the issue of the importance of alcohol in the lives of Rai women from Bhojpur.

The documentary starts with a voiceover, where we hear a woman talking about how important alcohol is for Rai people. “Our ancestors used to say, we came out bathing in alcohol. We believe it’s our nature,” says the woman.

And from the beginning, through this voice-over, Rai clearly sets the tone of the film: she is interested in depicting the significance of alcohol for these women, who also represent the culture she belongs to.

The women, the subjects of the documentary, are real women from rural areas, for whom a drink every night numbs their life’s miseries.

Among the several characters, we see in the documentary, Nini (aunt) is a major character, who gets most of the screen time. While there is warmth in her tone, she has lived through a lot of upheavals in her life. Her son is unemployed. Flood took her field away. “Because of all the tension in my life, I started drinking,” says Nini. “But now it has been five years that I have stopped drinking alcohol, as my doctor had advised not to do so after I was diagnosed with depression.”

Likewise, there’s another character, Muma (grandmother), who proudly flaunts that she's the number one drinker in their village, making the conversations around her alcoholism laughable. But she too doesn’t drink for the sake of drinking.

Among the ten children she bore, three of them passed away. Then she found solace in alcohol, and she got habituated, she says. “I do a lot of work in the field,” argues Muma. “I get tremors when I don’t drink. I start shaking,” she says.

Since Rai is telling the stories of women of her own community, there’s an empathic understanding of these women, as she never portrays them as drunkards. They are people who depend on alcohol to distract themselves from the overwhelming pain they have suffered throughout their lives. Some have lost children. Some are mentally suffering. Some are tired from the monotony. And gulping down a few drinks every day is the only way they can trudge through life.

Another aspect that should be appreciated in the documentary is that Rai never tries to manipulate the audience, to make them feel for these women. Even if their stories are full of sorrow, there’s no sad background score added to generate sympathy from the audience. Rather, Rai’s direct representation makes the story more impactful, as whatever emotions the audience go through is real and organic than being manipulated by the filmmaker.

In a few scenes, we also see Rai interacting with these women. While we don’t see her in the frame, viewers witness the interactions between her and the characters, which feel warm.

And this ease between the director and the subjects reflects in her documentary, as her characters aren’t camera conscious at all. Rai has won enough confidence in her characters that it feels like they are unaware of the fact they are getting recorded. They speak as if they are talking with their own family members, due to which we as the audience get to see honest and heartfelt conversations.

The use of music is another aspect that should be praised in the documentary. The documentary starts with a high pitched background score, creating a sense of excitement among the viewers of what is in store for them. But as one by one the story starts unravelling, the crescendo starts falling, signifying the sadness of these women.

There’s this particular part that leaves a deep impression: that of a Rai wedding ceremony through which we as an audience understand how important alcohol is for them. But such moments are few. It would have been great if the director had also invested some time to let the audience understand the significance of alcohol in a more nuanced and a detailed way, explaining or showing other traditions and rituals, where alcohol is important and has to be used.

But there are a few other issues with the documentary, and one of them is timing. The length of the documentary is just 25 minutes and 50 seconds, and within such a limited time, Rai has tried to tell many stories which means none of the characters have a lot of depth.

Besides the two aforementioned characters, we also have a few other characters in the documentary and their stories aren’t powerful enough or have enough substance to move the audience. For instance, the character Chemma (kaki/aunt), who now has started a business of selling alcohol. Unlike the other women, she is young and doesn’t drink, but that’s the only thing we know about her. The director doesn’t spend enough time in helping the audience get invested in her story due to which her character is underutilised and forgettable.

The cinematography is also not exceptional, and the shots and frames are monotonous. This, however, perhaps can be discounted, since Rai is taking care of all things—the sound, camera, and even interviewing the subjects.

But the story itself is so strong that these weaknesses are overshadowed, as, within its duration, one is fully invested in the story wanting to see more and more, which for a filmmaker is a big compliment.

(‘Come over for a drink, Kanchhi’ will be premiered at the Nepali Panorama section of this year’s KIMFF festival, which will be held virtually from December 1o to 14)

Film: Come over for a drink, Kanchhi

Director, editor, and cinematographer: Sikuma Rai

Stars: 3 out of 5

20.81°C Kathmandu

20.81°C Kathmandu