Money

How Nepal became obsessed with instant noodles and why it’s here to stay

Thirty five years since it was first introduced, Wai Wai has taken over the country, becoming part of the Nepali staple diet. But not everyone is happy with its ubiquity.

Thomas Heaton

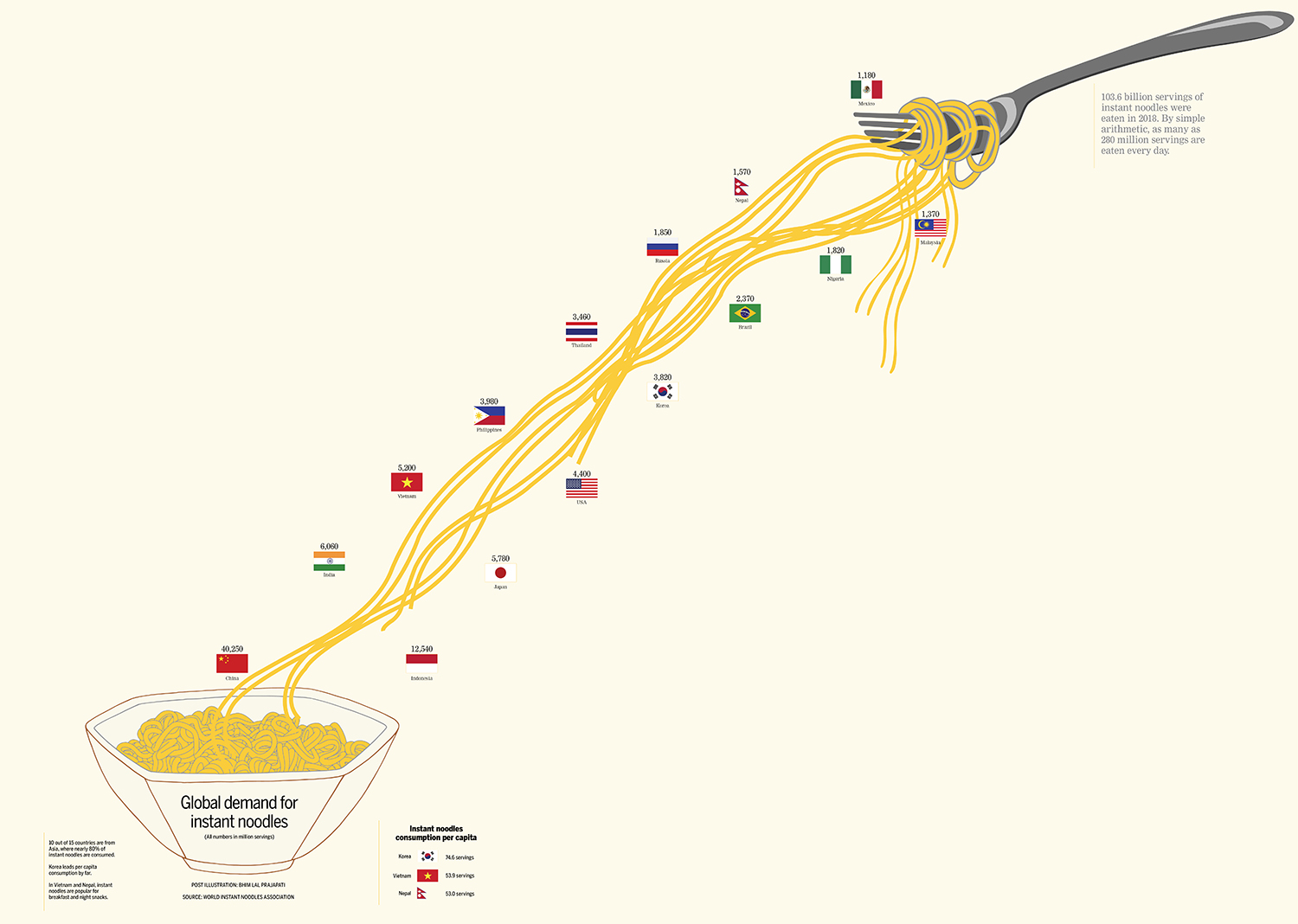

Every day, four million packets of instant noodles are consumed in Nepal. If you do the math, that means at any given minute, nearly 3,000 packets are being opened and eaten by Nepalis. But that’s hardly surprising for a country that is the third largest per capita consumer of instant noodles in the world, just behind South Korea and Vietnam and beating noodles-obsessed countries like China, Japan and India.

In Nepal, instant noodles are synonymous with Wai Wai, whose ubiquitous packages can be found just about anywhere in the country, from villages in the plains to hamlets in the mountains. Behind Wai Wai’s household presence is one man—Binod Chaudhary, often dubbed the Wai Wai billionaire. The Chaudhary Group chairman made his fortune on the back of this instant noodle, a product he introduced to the country in 1984, and in the process, turned his trademarked brand into an eponym for noodles.

In the years since it was first introduced, Wai Wai has gone on to take over the country, becoming a part of the Nepali staple diet, even replacing meals. But not everyone is happy with the noodle’s ubiquity, mostly because noodles by themselves do not constitute a full meal. Some even believe that instant noodles are behind the pandemic of junk food in the Valley, and more broadly across the country.

Instant noodles were invented by Momofuku Ando in 1958. The Japanese businessman, who went on to create Nissin Food Products, redefined the consumption of noodles by enabling people to ‘cook’ pre-cooked noodles in two minutes with boiling water. Following Ando’s ingenuity, the world took his noodle-dehydrating model and ran with it. In South Asia, adaptation of Ando’s plain white noodles meant adding spices and masala flavour packets, along with a distinctive style of brown noodles, one that Wai Wai would help popularise.

“The concept of ready-to-eat noodles didn’t exist in our part of the world. Pre-cooked meant you could eat it straight from the packet. It became a product you could easily differentiate from the competition,” said Nirvana Chaudhary, managing director of Wai Wai producers CG Group.

It took about 20 years for Nepali businesses to jump on to the wave of worldwide noodle popularity. Him-Shree Foods claims to be the first company to manufacture instant noodles out of all the SAARC countries—in 1979. Its most popular brand, Rara, is a white-flour instant noodle, a style widely distributed throughout the world under innumerable brand names. While noodles surged globally in popularity, it wasn’t until Chaudhary introduced Wai Wai to Nepal that the country’s market swelled, opening up an entirely new industry. Today, Wai Wai remains the undisputed king of the market, but there are hundreds of instant noodle brands saturating the country.

.jpg)

Becoming a national staple

Nepal might have a plethora of instant noodle brands, but they are generically referred to as either chau-chau or Wai Wai, epitomising the brand’s dominance. Sold for around a paltry Rs15 per packet, or less, noodles have become a mainstay in the Nepali diet, exemplified by the average 53 packets each Nepali consumes every year. A fact that Chaudhary himself has said proudly several times, in several different interviews—Wai Wai is a “staple” in the Nepali diet.

Him-Shree’s Rara noodles were already available when Binod Chaudhary introduced his pre-seasoned brown noodles to Nepal. Wai Wai is a Thailand-based brand—meaning “fast, fast” in Thai—created by Thai Preserved Food Factory in 1974, but CG adopted the label and brought it to the country in 1984.

Thai Preserved Food Factory had initially advised against taking their noodles outside Thailand, because it wanted to focus on its own country, according to Nirvana, who is also Binod Chaudhary’s son. But Chaudhary Group purchased the rights to the brand and began manufacturing the product under technical supervision from the original company—it still pays royalties to the Thai company. After setting up the first manufacturing factory in Kathmandu, under the Thai company’s supervision, the brand quickly took off, solidifying its place in the Nepali market and eventually helping turn Chaudhary into the country’s first billionaire.

The Post made several attempts to interview Binod Chaudhary but he was not available for this story.

Born into a business family that specialised in textiles and later, construction and international trade, as the eldest son, Chaudhary took over the family business when he was 18, according to his son. Not long after taking over the family business, his acumen was evident, having already set up Kathmandu’s first night club. Some time in the 70s, Chaudhary had already launched Nepal’s once-most popular biscuits—Pashupati—using excess flour from a mill his father had set up. When a surfeit of excess flour remained, he pursued instant noodles.

In several interviews, Chaudhary has recounted seeing travellers arriving at Tribhuvan International Airport with packets of instant noodles, and that’s when he sensed an opportunity. But Nirvana said that it was boxes of instant noodles arriving from Thailand, combined with what his father had witnessed while working in Japan—the world’s fourth largest instant noodles consumer—that germinated the idea in Chaudhary’s brain.

The ease of eating, along with once-consistent Rs11 price, made it a hit within just a few years. As the number of casual eateries across the country increased, so did the popularity of the noodles.

“What is the first thing they add to their menu? Momos, sekuwa and Wai Wai. It’s a low cost margin for them. It’s easy to make and the taste is already accepted,” said Nirvana.

Instant noodles have found their place in the country’s cuisine in the form of a soup, or jhol, sometimes with added vegetables; sandeko, with peanuts, chickpeas, onion and tomatoes; fried like chow mein; and even on the street, as chatpatay.

While Chaudhary likes the term “ruthless” for his approach to business, he has also attributed a lot of Wai Wai’s success to nostalgia.

Over the 35 years since the noodles were launched, the idea of remittance and labour migration has helped promote the business globally. “Because they grew up with Wai Wai, they have been the real brand ambassadors. They’re still consuming Wai Wai because it’s easy to carry and cook,” said Nirvana.

The brand now has 13 different flavours and, according to Nirvana, controls around 50 percent of the noodle market in Nepal, and 3 percent of the world’s noodle market.

While entrenched in Nepal, Chaudhary was quick to develop the business overseas, citing a restrictive domestic climate for growth, opening up several factories in India, and later expanding to Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Bangladesh and Kazakhstan, among others. It is exported to 35 different countries from various factories, depending on cost, selling close to 2.8 billion packets a year. The company is soon adding a new factory in Egypt.

Wai Wai’s Indian half-billion dollar market share has also grown 20 percent year-on-year, taking 28 percent of the instant noodles market, Economic Times reported last year. Wai Wai has as much as 80 percent of the market in India’s north-eastern states, according to Nirvana.

Opening a noodle market

While two of the country’s most well-known labels, Rara and Wai Wai, have solidified their place in Nepali bowls, others have followed suit.

“There was a time when we were undisputed 60 to 70 percent market share holders, but that’s when three or four really big companies came in and shook us up,” said Nirvana. Over the course of four decades since Him-Shree began producing Rara, about 20 companies have created a $220 million noodle industry.

The Pokhara-based Him-Shree, which currently only produces Rara, is in the midst of building a factory in Nepalgunj, General Manager Amit Thapa told the Post. While Rara’s brand name is strong, Him-Shree’s production of noodles has slowed because of increased competition and an upheaval of the company’s management, according to Thapa. Marketing has waned and so has production. Although, because Rara had such a strong brand presence in the market, there was still some demand, Thapa said. The company will ramp up production as soon as its capacity increases, with the new factory.

CG’s Nirvana said that Wai Wai’s white noodle varieties, such as spinach, tom yum and aloo tama, have been working hard to shore up their place in the market. Considering economies of scale, however, CG’s white noodle drive has been competing strongly with Rara, he said.

“We’ve sort of given them a tough time. They’ve done a fairly good job in terms of white noodles, their product is very nice,” he said. “But the white noodle market is very small, actually. I would say it’s less than five percent of the total noodle market.”

Asian Thai Foods, which began producing RumPum in 2000, has a litany of brands available throughout Nepal and commands 28 percent share of the market, according to Managing Director Mahesh Jaju. He attributes CG with starting Nepal’s noodle obsession, and now considers them its only real competition.

At the time of the company’s inception, the brunt of distribution was focused in urban centres, said Jaju. The decision to start the business was to capitalise on the dearth of Nepali noodles in the Tarai, and to feed the hungrier far-flung regions.

Like Wai Wai, Asian Thai Foods started with RumPum brown noodles, because they’re pre-fried, dried and contain preservatives, and are generally preferred over white varieties.

“It’s popular because it’s easy to eat, and it’s the only style of noodle in Nepal that you can eat it safely without cooking,” said Jaju. Him-Shree’s Thapa, however, says white noodles are also safe to eat straight from the packet. Still, brown noodles such as RumPum are so popular that despite competition, Asian Thai Foods posts an annual $10 million turnover and sells at 25,000 retailers countrywide.

Jaju also claims that his company is the largest Nepali exporter of noodles—shipping to Indian states Bihar, Bengal and Assam, and Australia, Malaysia, Qatar and the US.

Wai Wai, as a mega company that produces tonnes of noodles every year, exports noodles from one of its several factories, depending on market prices and taxes. From Nepal, it generally exports to the US, the Middle East or Australia. “But there’s still a lot of markets that we haven’t tapped into yet,” said Nirvana.

Relative newcomer Siddha Vinayak launched the brand GaZzabko in 2017. Now, it already has brands Dosti, Khushi and Koseli, and exports to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, with plans to reach Bangladesh and the Gulf countries soon.

Abishek Shrestha, the managing director for the company, told the Post that the earthquake and the Indian blockade contributed to the rise in demand for quick and cheap meal replacements, so they saw a business opportunity.

“Also, in the hilly regions, where proper vegetables are not available, people use instant noodles as replacement. So the industry grew dramatically,” Shrestha said. While 50 percent of the noodle market lies in Kathmandu Valley, the hills and mountainous regions are equally in love with instant noodles.

Shrestha said Siddhi Vinayak is producing somewhere between six and seven million packets of noodles each year, and the GaZzabko and Dosti brands are most popular. He says the company has five percent of the “very fierce” market.

“We have a huge capacity of production, but due to high amounts of competition in the market, we are not able to use our full capacity,” Shrestha said. Increases in excise duty and rising prices of raw materials are also affecting the company.

While domestically hundreds of millions of packets are produced every year, the country still imports numerous foreign brands. These, however, do not compete with domestic instant noodles, because of their higher prices, he said.

“Our product price is Rs20, so the consumers are different. We don’t have any competition from them [foreign brands]. But their market share is growing,” he said.

Him-Shree’s Thapa disagrees.

“It’s not only competition for us, but for the whole noodle market,” he said. “Imported varieties have taken a good portion of the market—somewhere around five percent.”

Despite the price difference, Thapa sees foreign brands as a threat. He further asserted the difference between white and brown noodles, stating that these too are distinctly different markets. Part of that difference is nutritional value.

.jpg)

“Tasty and Healthy” — or is it?

Wai Wai should have never become a staple, according to Atul Upadhyay, a food technologist.

“Everyone does eat Wai Wai, but how do they eat it?” said Upadhyay. “The Chinese and the Japanese mix their noodles with vegetables and other foods. We only have spices, oils and chilli powder—and the only point is to fill the stomach.”

Even Siddhi Vinayak’s Shrestha acknowledged that instant noodles were snack foods and fell under the “junk food” category. “Of course, we wouldn’t recommend high consumption,” he said.

Upadhyay said that part of the problem is that noodles, even though seen as snacks, have ended up becoming meals for Nepalis, especially young children.

“Our traditional staple is dal, bhat, tarkari. The combination of rice and lentils provided enough protein, while vegetables are an excellent source of vitamins and minerals. If there is dairy or meat, then it is a complete meal,” he said.

Wai Wai claims to have set the trend of fortifying products, in 2006, and later launched other labels such as its five-grain brown noodles. Many other brands also carry health-focused slogans, such as Rara’s “Tasty and Healthy.”

The slogan is relative, according to Thapa, HimShree’s general manager. The noodles themselves are simply flour-based, and are nutritionally better than other brown noodle options. “But they’re not a health supplement,” he said.

Nirvana Chaudhary, however, says there’s a wrong perception about noodles.

“We’ve never come across any examples where Wai Wai has been the cause of stunting, or where it can be remotely categorised as junk food,” he said, quickly pointing to the company’s campaigns with the United Nations and World Health Organisation to ensure that the product follows specific health guidelines. Nirvana said the idea that CG’s noodles are healthy needs constant reiteration.

“We are constantly pushing how Wai Wai has all the right nutrition and nutritional value,” he said.

Chaudhary Group has also teamed up with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for a project called “Baliyo Nepal”, which will fight against malnutrition and all associated health problems, said Nirvana.

“It’s a movement and we’re trying to get other producers involved,” he told the Post. “The idea is that rather than giving them supplements, why not make the existing products that they’re consuming rise to that level?”

The project will be formally announced in September, and launched in an undisclosed province, with fortified CG food products, and would be rolled out countrywide next year. “We will definitely start with noodles, and then move to juice in the later stages,” said Nirvana.

While some noodles are fortified with added micronutrients, such as iron or calcium, whether or not fortification actually makes any difference is another question all together, nutritionist Upadhyay says.

“The high amount of sodium would certainly negate the fortified flour’s benefits. Then, the bioavailability of certain ingredients is unknown,” said Upadhyay, referring to the several processes that put the noodles into the packet. Vitamin A, a typical additive, has been proven to be absorbed when consumed with oil as its conduit, he said.

“The big thing that is often overlooked is once a child eats instant noodles, their stomach will be filled and they won’t eat other foods that actually have health benefits,” said Upadhyay. “You can still make noodles a healthy product. If you substitute refined flour with whole-wheat flour, that would increase the fibre content and increase vitamins and minerals.”

Noodles are typically manufactured through several different processes that include air-drying, high-temperature steaming and frying, or dehydrating, before packaging. Upadhyay said the quality and potential absorption of extra ingredients that fortify such products is unknown in Nepal, but could certainly be affected by the extreme temperatures they are subjected to.

Clinical nutritionist Bhupal Baniya told the Post that even though white noodles were slightly healthier than brown varieties, both were void of any real value. Trans and saturated fats, and high levels of sodium contribute to their unhealthiness.

“Noodles contain so many things that can be harmful to your health,” Baniya said. “And that’s not just for children, it’s for anyone who eats it. It’s simply not a healthy food.”

Although current laws make inclusion of nutrition labels and information voluntary, many instant noodle brands opt to print them on their packets. If businesses choose to include them, they are then sampled by the Department of Food Technology and Quality Control for veracity. They must also clearly state what preservatives and flavourings are added.

Senior Food Research Officer Mohan Maharjan said that protein, acid and peroxide levels in instant noodles are also monitored as part of the office’s work. However, on the whole, monitoring of things like fortification is a low priority.

“We have made the standards that are mandatory, so we monitor those things. We check them at the time of licensing and relicensing,” said Maharjan, referring to annual relicensing processes. “But, when it comes to noodles, it happens very rarely.”

Despite most noodle brands electing to put nutritional information on their packets, Nepalis rarely care about them, said Baniya.

“Even educated people aren’t concerned about what they are consuming,” he said. “Why isn’t the government concerned about this?”

.jpg)

The MSG conundrum

The Department of Food Technology and Quality Control monitors various facets of the production process, but predominantly focuses on moisture levels. When it comes to MSG, the frequently used acronym for monosodium glutamate, instant noodles must not surpass one percent of the product’s total weight, and a warning on consumption for those younger than 12 months is mandatory. Representatives from noodle companies that spoke to the Post refuted any negative health claims associated with MSG.

Upadhyay’s first job was as a quality control officer at the Wai Wai factory in Nawalparasi, about 20 years ago. Even though he works in nutrition issues now, that was never a concern while he was at the factory. He was mainly charged with the responsibility of making sure products were shelf-stable and safe to eat, said Upadhyay.

“Our concern was whether these foods were safe for consumption or not. The government was only interested in the microbiological content,” he said. That meant the brunt of testing done was regarding moisture levels—whether the noodles could harbour mold or bacteria.

Almost all brands have landed themselves in hot water in past decades, either for excessive lead or MSG content. In 2015, Maggi and the Nepali brand Mayos were pulled from shelves, when inflated traces of MSG—also known as preservative 621—were found in products that claimed to have none. Indian state Assam banned Wai Wai’s 1-2-3 brand in the same year, citing public health concerns over high levels of MSG. While the salt, widely credited for the savoury “umami” flavour, is naturally occuring, manufacturers use it in its purest, refined form.

While MSG was once maligned world-over, following a study that dubbed the salt a danger to health, people’s views are changing. The symptoms of overeating the salt were called “Chinese restaurant syndrome”, but later labelled “MSG complex”. However, like in Europe, Nepal does have limitations on how much MSG these companies can use in their manufactured foods.

“MSG is contentious because there are a few publications that say that it may lead to malformation of bones [in children],” said Upadhyay. “At the same time, there are also reports that suggest it is not harmful.”

There are warning labels on noodle packets that contain MSG, and the government does test MSG levels in food. According to the Department of Food Technology and Quality Control, packaged food should not have more than one percent of its mass from MSG.

But despite qualms over MSG or any attitudes towards health effects, Nepali bellies still yearn for instant noodles. While Him-Shree’s Thapa said it would be unviable for another company to enter the fold, with increased prices for raw material and excise duties, the sheer amount of competition, and the competitively low price points would make it a difficult pursuit. But for Chaudhary Group, there’s still plenty of room for expansion—at least for Wai Wai.

Despite the health concerns and absence of nutritional value, there’s no denying that instant noodles, particularly Wai Wai, hold a special place in the Nepali cultural psyche. In fact, its influence is so unavoidable that even those who point to health concerns recognise that Wai Wai has become an institution—and the product is here to stay.

“It’s not that we don’t eat Wai Wai in my family,” said Upadhyay, the nutritionist. “But we add an egg or broccoli, and it becomes a colorful treat.”

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu