Interviews

Double standard of political leadership on school education is problematic

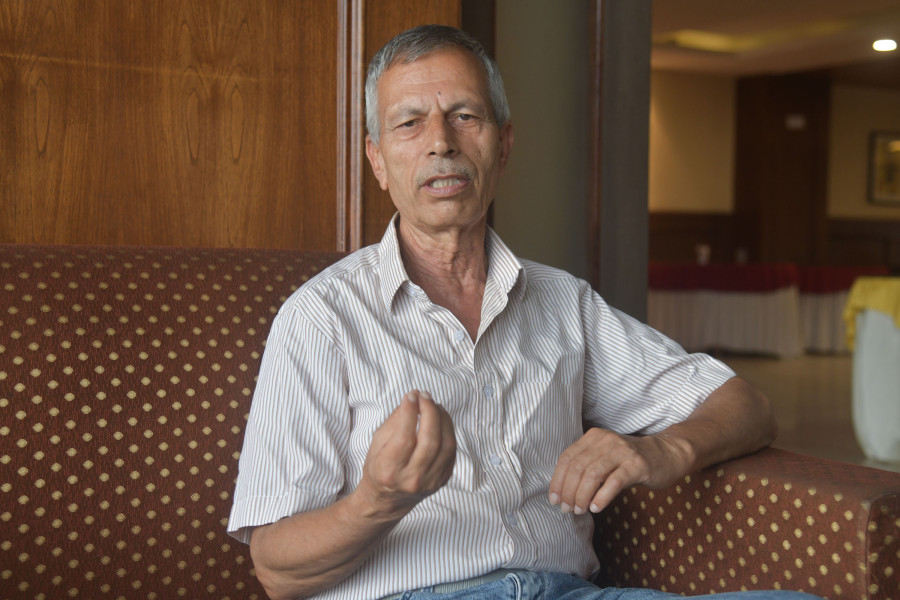

Educationist Bidya Nath Koirala, professor at Tribhuvan University and a member of the High Level National Education Commission, on different aspects of School Education bill.

Binod Ghimire

The School Education bill registered in the House of Representatives after a long preparation has met with criticism from different quarters. Except for private school operators, all school-education stakeholders have criticised it. The Nepal Teachers’ Federation even staged Kathmandu-centric protests parading thousands of school teachers in the streets of the Capital. Though it has called off its protest after reaching a six-point agreement, a section of the teachers is still in protest. Similarly, the umbrella bodies of local governments and the association of over 430 non-government organisations working in the education sector too have stood against different provisions in the bill. Against this backdrop, Binod Ghimire from the Post talked to educationist Bidya Nath Koirala, professor at Tribhuvan University and a member of the High Level National Education Commission, about the different aspects of the bill. Excerpts:

How do you see the bill that has landed in the Parliament after a long wait?

It is written in good language. There is citation of the constitution and justifications have been presented for each provision but there are several problems in its content. It is influenced by interest groups while several provisions are incomplete. It says the private schools can convert into trusts if they wish but there is no option of them converting into cooperatives. Similarly, it doesn’t speak about the design of collaboration between the private and public schools and the responsibility of private schools to cater to children from poor and marginalised communities. There is no provision about school zoning either.

School education is under the explicit authority of the local government. At the same time it is also under the concurrent authority of all three tiers of government. However, the bill has failed to clarify to the stakeholders whether it is based on explicit or concurrent authority. There are several such lapses.

Why was the bill so controversial?

This is because our lawmaking process is not transparent. Let alone hold consultations, people in government didn’t even entertain the suggestions given voluntarily. I personally tried to know about the content of the bill before it got endorsed. Officials from the education ministry said they didn’t have any such draft bill. I then talked to a personal aide to the prime minister who asked me to give suggestions. I did as he asked but I never got a response. It speaks volumes about the mentality of our governments. The teachers complain that they were not even allowed to see the bill.

What is the problem in seeking feedback from stakeholders on the bill targets? The present controversy could have been avoided had there been proper consultation with the teachers, local governments and the private schools.

Don’t you think the bill appeases private schools?

That is not surprising. There is no political party without leaders who own private schools. Every party takes money from these schools. So it is natural that no law would be prepared against the interest of private schools. Private schools have captured close to 30 percent of students’ volume. They have a dominant presence in towns and cities. Over-politicisation of public schools is only increasing their attraction.

You have expressed your concern about the ever-increasing grip of the private sector in school education. How can it be minimised?

The problem is a double standard of the political leadership. They promote private schools but in public they are very critical of the same schools. It would be extremism to talk about the closure of all private schools. However, it is important that we do proper zoning of schools and bring policies to build partnerships among public and private schools. In the high level commission’s report, we had recommended limiting private schools either to early childhood development level or technical education or higher education or some specific geography. It is vital to devise policies to properly manage private schools.

Has this bill internalised any suggestion from the high level commission?

The commission had proposed to end teachers’ direct involvement in politics. If not, the teachers affiliated to a particular party would work to implement the education policy of their mother party. For instance, the CPN (Maoist Centre) talks about people centric education policy. At least the teachers carrying the Maoist ideology should act to translate the party’s education policy into action. Also, we can find a meeting point in the education policies of all political parties and implement them. Today’s problem is lack of effort in finding a solution. If the parties are willing, we can find several ways to solve the problems facing the education sector.

Don’t you think the bill’s provision to bar teachers from partisan politics is positive?

There is also a double standard of political parties. If the parties don’t have a sister wing of teachers, the problem will be automatically solved. But the parties continue to have teacher wings while they also come with the law to bar teachers from politics.

It is the political parties that need teachers more than teachers need them. Can these parties announce that they have dissolved their teachers’ wing?

How do you see the agreement between the government and the teachers’ federation?

It has at least ended a protest by a section of teachers. However, it has left several questions unanswered. The role of the local governments is still unclear: Whether they have explicit authority over school education as prescribed in Schedule 8 of the constitution or it is a concurrent right of all tiers of governments as envisioned in Schedule 9. Whether teachers will get trade union authority while they continue to be affiliated to the parties is also not clear. The pay and perks provisions are also rather vague.

The agreement hasn’t completely ended the problem. The teachers under relief and temporary quotas are still in protest. How do you see it?

This is troubling. As per the agreement, 75 percent of such teachers will get to compete internally for permanent postings. I am against making teachers permanent without free competition. The government can give existing teachers a few years for the preparation of competitive tests. However, no one should automatically get permanent posting. The agreement between the government and teachers asks the government to set the order of precedence of teachers. It would be immoral for the teachers appointed through protests and without facing competitive tests to remain in the state’s order of precedence.

Appointing teachers without free competition will bar the entry of a competitive workforce, which will be injustice for millions of students. It will prevent them from getting a quality education. This will further deteriorate the quality of education.

What suggestions can you offer to make the bill more acceptable?

The government should not press ahead with it in Parliament. It should rather send the bill to all the stakeholders asking for their suggestions. Then it can finalise the bill after holding proper discussions with the stakeholders and experts.

Can’t this be done through the parliamentary process?

Yes, the lawmakers can register amendments to the bill. However, based on my past experience, I doubt whether individual lawmakers can go beyond the dictation of their party to revise the bill to address the ongoing problems. There is a trend of ruling party lawmakers not challenging the bill introduced by their party. Similarly, others act as directed by their parties. If you don’t work with an open mindset, you will not be able to find solutions. I thus believe the correction process should start before the bill is tabled in Parliament.

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)

.jpg&w=300&height=200)