Interviews

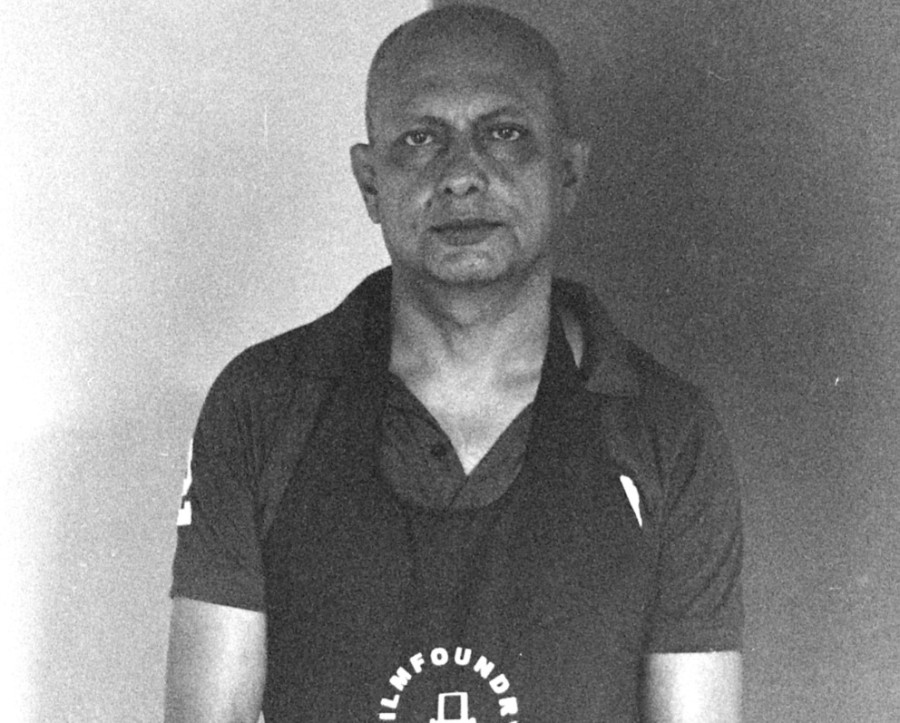

This is a renaissance for film photography in Nepal: Jagadish Upadhya

While the camera industry and culture is digitally-focused now, this Nepali photographer is trying to preserve its purist form.

Sanjog Manandhar

Despite travelling to France to study aviation in 1986, Jagadish Upadhya came to realise he had more of an eye for photography. Engaged with people invested in creative art and photography, he decided to drop his piloting career to pursue photography. In 1989, he enrolled in an art-photography school in the United States—now, more than 25 years later, he is still active in photography.

His passion for film photography will be explored in an exhibition titled ‘Life in Analogue,’ where photos taken from analog cameras during the period of 1900-2019 from 46 participating photographers will be displayed at Siddhartha Art Gallery from August 4-18.

In this interview with the Post’s Sanjog Manandhar, Upadhya discusses his passion for traditional film photography, his efforts to preserve the art, and his business Film Foundry. Excerpts:Why is film photography important to you?

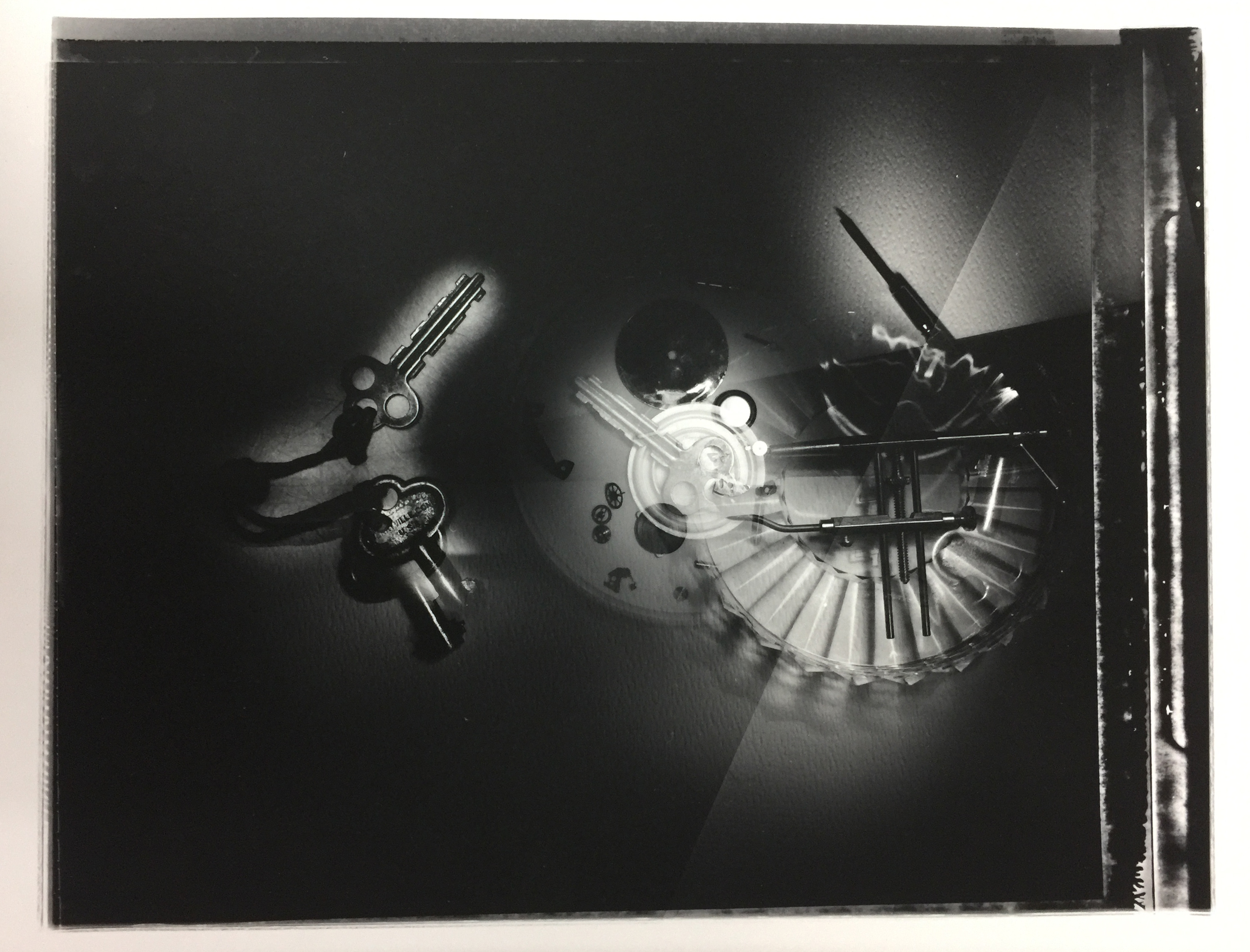

When I started pursuing photography, it had already evolved into digital photography. But I was more attracted to film photography because I felt it makes a different impression. As a photographer, film keeps me physically involved—movement of body and hands keeps me focused and engaged, both physically and mentally. My passion for film is still intact, not just about the medium but of the whole process of printing photos and all the darkroom techniques. This is what still drives me.

What do you know about the history of film photography in Nepal? Who were the pioneers in this field?

I think Gopal Chitrakar and his family were among those who made a significant contribution in film photography. Because of their access to the then-royal family, they were able to develop the trend of photography in Nepal. Other than that, there were many influential people who had film cameras. Among them, there were 10 to 12 photographers who made significant contributions but some of their identities and work are still shaded from the limelight.

But they didn’t envision the value of their photography as something worthy of documenting the history. They never realised that after 100 years, their photos will be valued.

Who was your inspiration when you started? Did you have any mentors?

Robert Doisneau, a French photographer, was my inspiration and, fortunately, was my mentor too. His book on Paris street photography amazed me. Since I was there at the time, all those photos made a huge impression on me. His works captured not just images of daily life, it was more like a visual storytelling.

Apart from him, I draw inspiration from the works of Irving Penn, Henry Cartier Bresson and Robert Cappa. Currently, photojournalist Steve McCurry’s works have been on my watchlist.

Purchasing cameras and accessories is a heavy investment these days. Was it as expensive when you started shooting?

Even in those days cameras were very expensive. New gear and cameras with new features were constantly introduced in the market—just like the contemporary market. But, in film photography, even with the basic camera and darkroom technique, you can produce a good photo.

Film was expensive but it was readily available in the market. Most people used to have cameras in their home, and photos were valued and taken to be prized communal possession within families. These days we take many photos from digital cameras but it doesn’t carry the life printed photos do.

In today’s digital era, photos are like personal property which exists only in electronic gadgets. Once the power is off, photos disappear. But before, it was different, family members used to gather around the table to look at the photographs—it was like sharing happiness.

How long did it take for the film to develop? How accessible were printers in those days?

There was a time when people used to send their film rolls overseas to get them developed. But later, equipment required to develop films into print were brought to Nepal. People started making glass plates too—that was more like an artisanal work.

The access to print, however, was very limited in the 80s—when photography was getting popular with everyday people.

If photographers want to pursue film photography today, what are the challenges they may face—in terms of availability of equipment and investment?

One of the major challenges is the availability of cameras and film rolls in the market. In black and white films, there is a certain amount of silver content, and due to the rise in the price of silver, buying black and white film has become very expensive. Another challenge is to get your hands on the film-roll cameras. The production of such cameras has plummeted since the rise of digital cameras in the market. Though there are few companies still making film cameras, most have resorted to going digital.

But if you are really passionate about film photography, you can search for second-hand cameras—which may be sitting in someone’s cupboard or basement unused and abandoned. People will be ready to sell their old cameras from Rs 10,000 to 15,000. Film rolls cost around Rs 400-500 too. So, if you are really interested, start with an investment of Rs 25-30,000.

Can you tell us about Film Foundry?

I started Film Foundry to make it easier for photographers to access to roll-film cameras, accessories and darkrooms. This place is more like a platform where people can learn and share their knowledge about film photography. It serves those who are passionate to learn about film, and hopefully it contributes in the growth of film culture.

How many photographers are currently engaged with film photography?

I think there are more than 50 photographers in Kathmandu currently involved in film photography. They are mostly pursuing it in an ad-hoc manner, but their involvement is still very crucial. Some photographers, who had left the field due to the absence of a darkroom, are also coming back.

It is like a renaissance for film photography. I hope this community will grow more and those who had left will also be open to sharing their knowledge and experience.

Is it possible to make a living by doing film photography?

You have to struggle regardless of the profession. But since photography is more about one’s creativity, you will have to create your own job rather than relying on someone else to make an offer.

I see a lot of possibilities for those pursuing artistic film photography. Portrait photography doesn’t exist these days but there was a time when people were obsessed with the artform. Film photographers can revive trends like these—this is only one example.

In European countries, there is a new trend where people visit a studio to take their photos and get it printed through a method known as tintype—photos that are printed directly on aluminium plates to give a vintage look. This can be replicated in Nepal too. There are endless possibilities, we just need to look beyond the norm.

What are your future plans?

I will stick to developing the film culture in Nepal. I am interested in sharing my printing skills and techniques, because there are many approaches. Since this is all about handwork and artistic skills, I want to use handmade paper, like Nepali paper, or other local materials for printing. So my interest is to expand printing skills.

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)