Health

Hooked up to a machine

Nepal provides free dialysis to poor patients, but psychological counselling is missing.

Nimisha Gautam

“Are you satisfied with your life?” I ask a 47-year-old haemodialysis patient at Green City Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal.

“Satisfied?” she laughs sarcastically. “I’d rather wish I were dead.”

End Stage Renal Failure (ESRF) is a chronic kidney disease which occurs when both kidneys stop responding to the body’s demand to filter out necessary wastes and excess fluids. When the kidneys do not function in the way they are designed to, unwanted substances, which are ideally supposed to be excreted from the body, accumulate, causing detrimental to life-threatening consequences. The ideal treatment for an ESRF patient is a kidney transplant, the process of replacing the damaged kidney with a healthy one from a living/deceased donor who is a potential match.

This is easier said than done. A kidney transplant is, quite frankly, a shot in the dark. After the patient is added to the transplant waiting list, the quest for a matching kidney could take anywhere from one day to half a decade or more. The patient needs to meet each and every requirement—from an exact nutritional status to appropriate blood level to physical tolerance. Then, there’s always the worldwide organ shortage obstacle.

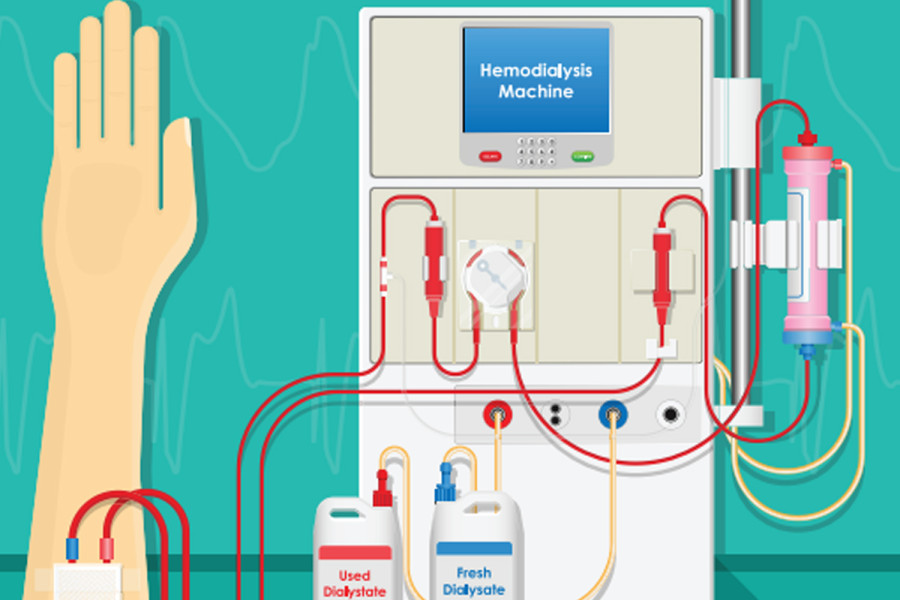

While patients are on the constant lookout for a matching kidney, most of them are obligated to get dialysis as an alternative. Haemodialysis is a type of dialysis where patients are hooked up to a human-sized machine which holds an ‘artificial kidney’, commonly known as a dialyser, which filters and cleans the patients’ blood. An accessway is made by connecting an artery and vein (known as a fistula) through a minor surgery which assists the blood to leave the body, get processed in the machine and circulate back into the body. This medical technology is not only fascinating but also lifesaving, as this machine perfectly mimics the human kidney.

Kidney dialysis patients are required to come into the dialysis centre two to three times a week and spend three to four hours hooked up to the machine. The average cost of a dialysis session in Nepal is around Rs2,500. There are around 100 haemodialysis centres, equipped with 570 haemodialysis machines in total. As of 2021, around 4,500 patients were receiving this treatment across Nepal. Due to the high demand for, and cost of, haemodialysis, the government of Nepal has been providing free lifelong dialysis services to patients who cannot afford it. This has been a huge relief for low- and middle-income families in Nepal, who rely on these machines to take their next breath.

The Nepal government takes pride in the way it has allocated the health budget to facilitate ESRF patients, and rightfully so. But unfortunately, the moment they hand over the money, they turn their backs away to celebrate, not concerning themselves with what happens with it or after it. After interviewing around 110 haemodialysis patients across multiple dialysis centres in the Kathmandu valley the past summer, I discovered that almost all the patients appreciate this monetary gesture by the government.

“I don’t have that kind of money. Paying Rs2,500 for each dialysis session would’ve been impossible. But thanks to the government, I live to see another day. In fact, I’ve been getting free dialysis services for almost eight years now,” said a 68-year-old male patient, content. That said, money can only help so much. There are still many things necessary to improve not just the physical health of these dialysis patients, but also their mental, social, and environmental health and their quality of life in general.

Haemodialysis may have been a lifeline, a literal second kidney for thousands of patients in Nepal, but ironically, this medical milestone has left numerous ramifications along the way, affecting patients’ quality of life. For the rest of the world, it just looks like they are receiving top-notch treatment for a chronic disease, and that too, for free. But it’s only when you’re bedridden, alongside a machine beeping continuously for 4 hours straight, attached to you with a bunch of artificial tubes, as your crimson blood leaves your body and returns, that you realise how drastically your life has changed. Fortunately, these ramifications, if addressed with proper awareness and knowledge, can be mitigated with ease.

Nepalis greatly value the sense of community; this is evident even in the hospital hallways and waiting rooms. After going from one hospital bed to the next, one patient to the other, I could (for most patients) see a family member, friend, or relative alert and active beside their bed, either conversing, running errands or simply just being present. Almost all patients had a very positive response when I asked them how involved their families were in their treatment journey. But I realised that these people are more than just family members to these patients—they are caretakers. These dialysis patients spend most of their time in their homes, most of them bedridden, meaning they rely on their family for even the most basic activities like eating, using the toilet, going to the hospital, and taking their medications. The family has a big shoe to fill, and it is so visible that they are trying their best. However, while their intentions and hearts are in the right place, many of them are not aware of what to do. Do they understand what ESRF is? How dialysis works? What food must the patient eat? What food to absolutely avoid? How much salt is okay? How much protein should be provided to the patient? What medications to give and when? Do those medications have adverse effects on their other health conditions (like blood pressure, heart problems, and blood sugar levels in the case of most patients)? While some families do, the sad reality is that many don’t.

Most people seeking free dialysis services in Kathmandu belong to low- and middle-income families. Some have travelled hours from their villages to the city, hoping to receive the best treatment. According to my interviews, the majority have had primary to no education. One cannot expect the patients nor their families to have pre-existing knowledge about ESRF, a chronic illness so daunting and overwhelming. One also cannot simply hook the patients into the dialysis machine like it is any other day. The most important part right after the diagnosis and before the prognosis should be to educate. Educate the patients and their families about what’s happening to them, their treatment options, and what to expect. A 5-minute briefing from the doctor before they take away the patient to the treatment centre does not help. The government should invest in giving a detailed briefing to the patients on their illness and interactive training to their family members on the right way of taking care of these ESRF patients. Every bite of food and every sip of fluid makes an impact.

Dialysis patients' quality of life is impacted not only by their social and environmental health, but also—and heavily—by their mental health. I visited three hospitals, one of which is the National Center for Kidney Patients, meaning an entire building, all its resources and staff dedicated to kidney-related health problems. Floors and floors of kidney patients coming in for dialysis. Each hospital was well-equipped and well-funded. Yet, a crucial resource was scarce in almost all of them—there was little to no mental health support or resources for patients. I was there to interview patients, all of whom came in for the same treatment, yet each patient had a different story to tell. Just sitting alongside their beds for as little as ten minutes revealed to me how they process this life-changing treatment. I empathise with every single one of those patients who are relentlessly fighting this brutal disease; I am so thankful for their time and greatly inspired by their optimism and resilience in a difficult time like this. Behind those hundreds of patients are hundreds of stories:

My first patient, a 71-year-old woman, told me her illness is just God’s way of reminding her what a supportive and loving family she has. A 17-year-old boy has mastered the skill of playing video games with one hand while the other is hooked to the machine. A 32-year-old man rues that, in the age of providing for his family and bringing home the meal, he is bedridden while his wife works tirelessly every day. A 46-year-old woman, with tears trickling down her tired face, told me death seemed like an easier option than this. A 63-year-old man did not want to speak to me because he was tired of young people coming in and interviewing him.

These are a few of the many dialysis patients processing this life-altering form of treatment. Not knowing how long, coming in every single day for the same treatment for something that once was a seamless, natural process is a lot to take in. While we cannot make this treatment process any less daunting in terms of the medication and technology available, what we can do is make it a little less overwhelming for our patients: provide them with therapies and mental health counsellors, professionals who can help them deal with the plethora of emotions they undergo, or someone who listens and talks to them, so they no longer feel useless or a burden to others. Instead of considering them a sensitive subject, our focus should rather be on giving them hope that they can fight this as they tolerate the hassle of keeping their body in order.

The research for this study was conducted in June/July 2023.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu