Health

Authorities enforced antigen tests but failed to increase numbers

Such tests at border points could have been helpful but they were few and far between, experts say.

Arjun Poudel

When the country was hit by a second wave of the coronavirus pandemic, a scrambling KP Sharma Oli administration, which failed to prepare for the looming threat, came under increasing pressure to respond. Most of the responses, however, were tepid. As calls grew for expanding tests, it enforced antigen tests along the Nepal-India border points through which people were crossing in droves. Most of them were Nepalis escaping the virus ravaging various cities in the south.

That the response was so half-hearted was evident from the fact that the antigen tests were being conducted just in hundreds, even though people were crossing the border in their thousands.

For example, in Province 2, the antigen tests were few and far between.

“We were performing antigen tests at district hospitals only,” Dr Shrawan Kumar Mishra, chief of Provincial Public Health Laboratory of Province 2, told the Post over the phone from Janakpur. “We do not have test kits in sufficient numbers. Nor do we have necessary safety gear, like booths and personal protective equipment, to perform antigen tests at border points.”

Expanding such tests at border points had become extremely necessary because India was reporting record high cases every day, and there were concerns that letting people in without tests and keeping them in quarantine if they tested positive could fuel infections in Nepal.

But with no antigen tests, or minimal antigen tests, people in huge numbers kept entering the country and went home without staying in holding centres or quarantine.

One of the reasons for the spike in cases in Nepal is said to be the surge in infections in India where many Nepalis go for work.

From a modest 13,000 new cases until March, India’s new cases shot up exponentially–crossing the 300,000 mark–that the entire world was concerned. In Nepal, authorities needed to step up measures almost immediately to manage border points. The two countries share an around 1,800-km-long porous border.

Public health experts and scientists say the government, which became complacent when cases were on the decline as though they had already beaten the virus, made some serious mistakes. They asked local officials to perform antigen tests but failed to increase the test numbers.

According to Dr Prabhat Adhikari, an infectious disease and critical care expert, whenever possible, it’s always good to perform polymerase chain reaction tests.

“When PCR tests are not possible, antigen tests are fine. At least we can say something is better than nothing,” Adhikari told the Post. “But such tests should be conducted in huge numbers, not in hundreds.”

A rapid antigen test to ascertain coronavirus infection itself is not bad, as it returns around 85 percent accurate result in cases of symptomatic patients and 60 percent in cases of asymptomatic ones.

The good thing about a rapid antigen test is it provides results fast without the requirement of complex machines and laboratories.

But some protocols have been put in place by the government as well as the World Health Organisation.

As per the protocol prepared by the Health Ministry, if an antigen test shows a positive result, a polymerase chain reaction test is not required, and polymerase chain reaction tests are needed for symptomatic patients, even if an antigen test yields negative results.

The protocol also says that antigen-based tests are performed for mass testing, when urgent reports are required and such tests are performed on people living in congregate settings–barracks, prison and elderly care homes, among others.

Experts say the fundamental mistake the government made was it did not conduct tests in huge numbers.

With no holding centres and quarantine facilities at border points, the authorities just disseminated the number of antigen tests performed and the number of positive results. Whether those returning positive results were kept in quarantine or holding centres was not known, as authorities never made that information public.

“There is no point griping about antigen tests. The point is whether the tests were helpful or not,” said Adhikari. “For a good result, which in our case is curbing the spread of the virus, antigen tests should have been conducted on masses… in huge numbers and then steps should have been taken accordingly. Those returning positive results should have been kept in quarantine and isolation centres.”

Ever since the second wave arrived in early April, Nepal has been reporting a steady rise in the number of new infections.

On Monday, Nepal hit another record high number of new cases of 7,388 from 16,658 PCR tests conducted in the previous 24 hours.

The country also reported the single-day highest death toll at 37. So far 3,362 persons have died of Covid-19-related complications.

As of Monday, there are 54,041 active cases across the country. So far 343,418 have been infected.

Of the 518 antigen tests performed in the last 24 hours, 60 tested positive for Covid-19. In the last one week only 5,159 antigen tests have been performed throughout the country. And of them, 567 have returned positive results.

In the past week, a total of 103,747 PCR tests have been performed across the country. The past week’s positive results stood at 39,857.

When the country was hit by the pandemic last year, health desks were set up at various border points. But they were dysfunctional. Just as India declared its victory over the pandemic, Nepali authorities were quick to downplay the virus. But after the second wave, health desks were revived, but most of them are ill- equipped.

“We have been letting people go home directly advising them to visit hospitals if they develop any symptoms,” Laxmi Kanta Mishra, an information officer at Narainapur Rural Municipality in Banke, told the Post. “The number of people returning to the country is huge. It’s simply impossible to perform tests on all of them.”

There are three points along the border, Suiya, Ghoddauriya and Hulashpurwa, in Narainapur Rural Municipality in Banke.

According to Sameer Mani Dixit, director of Research at Center for Molecular Dynamics Nepal, antigen tests should have been and should be performed on all symptomatic patients crossing the border.

“Others can be allowed to go home,” Dixit told the Post. “But there should have been a system in place to perform antigen tests on them within five days of their return.”

According to Dixit, an antigen test detects at least 80 percent infection on people, who are symptomatic and have high viral load. Symptoms can be seen in five days among those who are infected but do not have symptoms.

“Performing tests within five days helps identify new cases, which were initially not detected at border points,” said Dixit. “Moreover, random antigen tests should be performed in communities, as the virus has already spread in communities.”

Public health experts and doctors, who had for long been warning the government about a looming second wave, have been consistent on their plea that the authorities must get back to basics–expand tests (both PCR and antigen), make contact-tracing effective and treat.

Nepali authorities failed to pay heed to the thumb rule of controlling the spread of the virus. Since the test numbers are low and the virus has penetrated communities, the infection rate is high.

The R, or reproductive, number which tells how many people one infected person can pass the virus on to also stands at a little over 2 in Nepal, meaning every single person carrying the virus is infecting two other people.

Doctors say Nepal is reporting a geometric growth of Covid-19 cases.

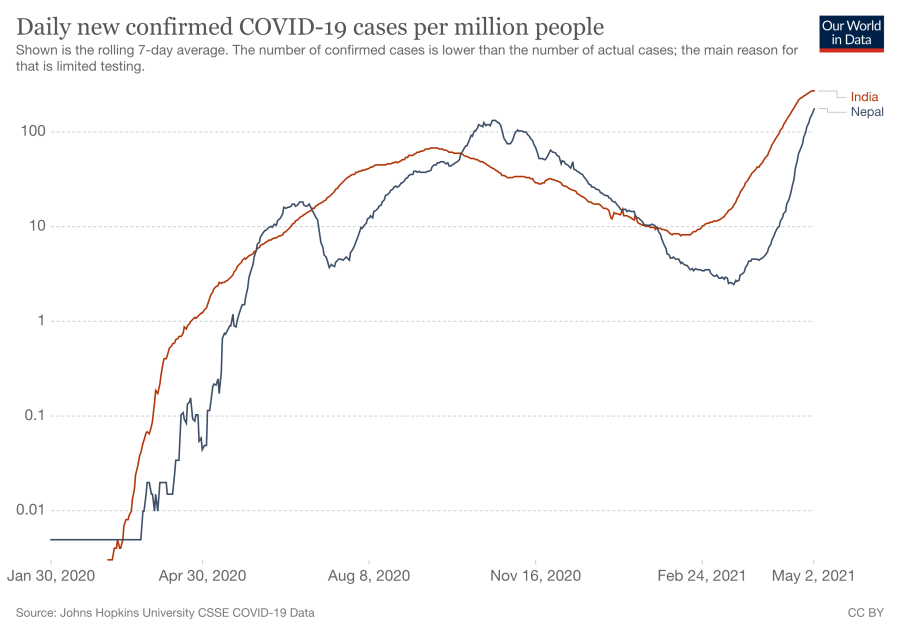

According to Our World in Data, when it comes to daily new infections per million people, Nepal, a country of 30 million population, is not far behind India, a country of 1.3 billion population, which on Monday reported 7,388 new coronavirus cases.

The government has projected that the daily number of infections could be as high as 11,000 by mid-July. The total number of infected persons could rise up to 800,000 and 15,000 could need intensive care beds while 45,000 might require high flow oxygen therapy, according to the projection.

“The most important thing to do to control the spread of the virus is ensuring effective contact-tracing,” Dr Keshav Deuba, a public health epidemiologist, told the Post. “Then comes testing. There is no other option than to expand testing, be it PCR or antigen.”

13.58°C Kathmandu

13.58°C Kathmandu