Health

When drug companies, pharmacies and doctors all benefit, patients pay the price

Drug companies are marking up the prices of their medicine to recoup their unethical investments in doctors and retailers.

Arjun Poudel

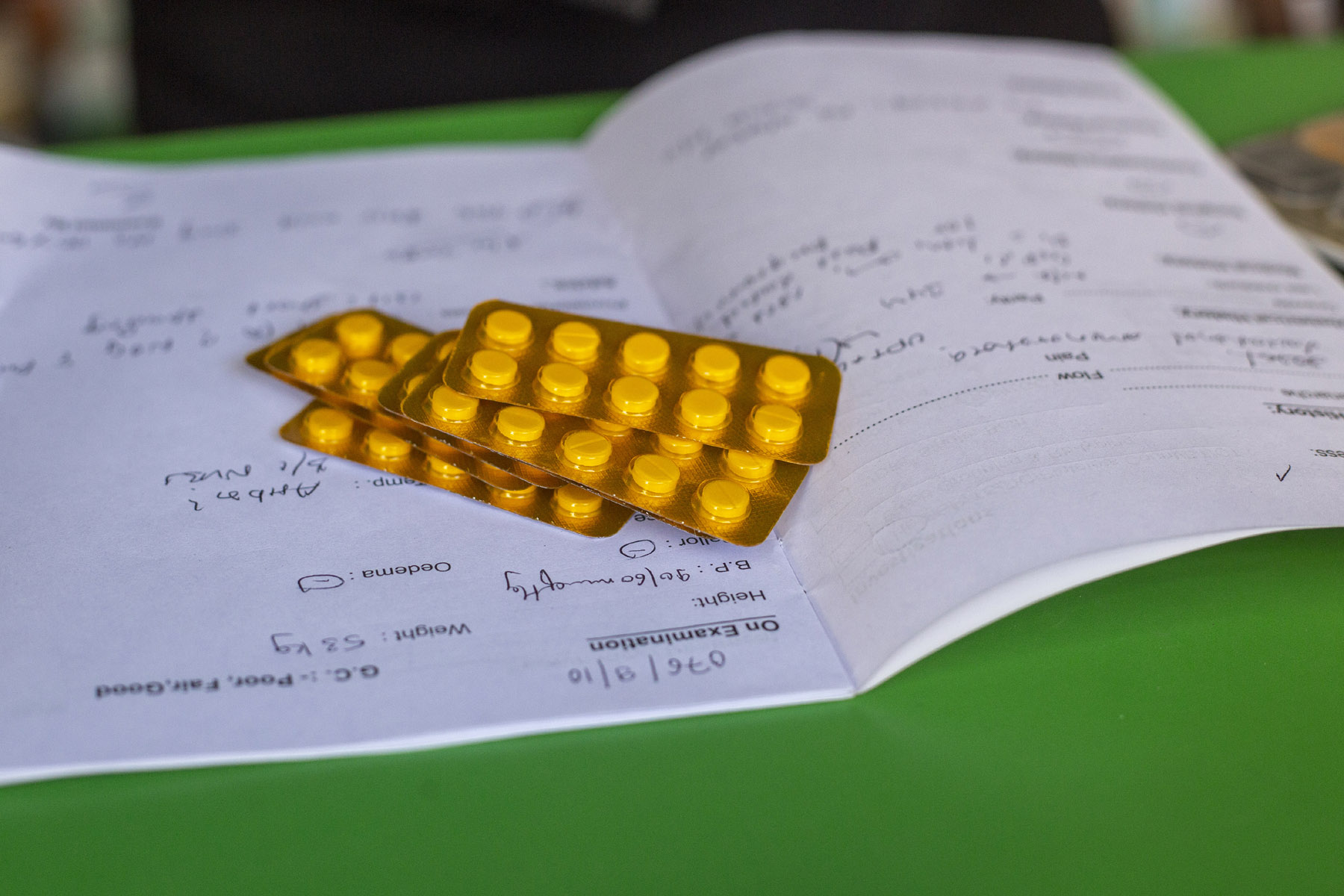

While purchasing medicine at the Paropakar Maternity and Women’s Hospital pharmacy in Thapathali, you might labour under the misapprehension that the price of medicine is dirt cheap. A 1 gram injection of paracetamol, whose listed Maximum Retail Price, or MRP, is Rs448, is being sold at Rs128.40. A 500mg injection of the antibiotic meropenem, whose MRP is IC410 equivalent to Rs656, is being sold at Rs312.

This is the case with most medicines the pharmacy sells. A cursory comparison of the listed MRP against the prices that the medicines are being sold at would lead anyone to think that they are getting a bargain--at less than 50 percent or 70 percent of the listed price.

But the hospital, which is Nepal’s oldest government-run maternity hospital, is not taking a loss for the benefit of its customers. In fact, even at these discounted prices, the hospital’s own doctors admit it still makes a profit of 20 percent.

This is largely because pharmaceutical companies, like most other companies, are allowed to set their own MRP, which leads to them marking up their products at exorbitant prices. They provide medicine to hospitals and pharmacies at a fraction of the listed price and most hospitals and pharmacies sell drugs at the inflated MRP.

But while public hospitals like Paropakar sell medicines at a modest profit, private hospitals and pharmacies tend to stake out a bigger pie for themselves, even charging above the listed price, sometimes making 100-200 percent profit.

“Drug manufacturing companies offer huge profit margins to other hospitals, but we share the profits with the patients,” said Dr Jageshwor Gautam, director of the hospital.

This fraudulent pricing of medicines is just one example of the deep-seated collusion among drug manufacturing companies, hospitals and pharmacies, and doctors themselves. Whether it has to do with pricing or prescribing medicine, the patients are the only ones at a disadvantage--everyone else profits.

Predatory pricing

When a drug manufacturer comes up with a new drug, they are legally required to register the product with the Department of Drug Administration. The manufacturer proposes their own MRP, which the department then endorses. Since there are no rules in the drug act regarding the setting of prices of medicines, companies collect the price of similar medicines produced by other national and international companies and set their own price. While doing so, they can either inflate the price or keep prices down. But most companies sell their medicines through promotional activities--either by offering incentives to doctors or providing huge margins to wholesalers and retailers.

Revital is a multivitamin manufactured by the Indian multinational company Sun Pharmaceutical Industries. It is a generic blend of a number of vitamins and minerals, used in case of anemia or a vitamin deficiency. It costs Rs 28 per capsule.

Revital has Nepali equivalents in the form of vigoran or fortiplex, which cost just Rs 5 per capsule in private dispensaries.

“Both medicines work the same, but doctors mostly prescribe the Indian brand,” Krishna Prasad Pandey, who operates a pharmacy at Naya Bus Park, told the Post. “We sell whatever medicine the doctor prescribes.”

Pandey, who is also an active member of Nepal Chemist and Druggist Association's Bagmati chapter, concedes that no pharmacy can run from the profit they can legally derive. As per the rules, pharmacies can charge 16 percent additional from the price they buy from the wholesales.

The quality, effectiveness and sale of drugs are monitored by the Department of Drug Administration and two legal frameworks--the Drugs Act and the National Drug Policy. Under Chapter 7 Article 27, the Department of Drug Administration “may, if it deems necessary, fix the price of any drug, by obtaining approval of the Government of Nepal.” Three years ago, the department’s Drug Price Monitoring Committee had fixed the price of 96 essential drugs, including paracetamol, albendazole, and oral rehydration solutions, but has not extended the list since then as the committee is not active anymore, said Santosh KC, the department spokesperson.

“Prices could have increased or decreased but there is no mechanism to check if the MRP set by the companies is reasonable,” said Baburam Humagain, general secretary of the Forum for the Protection of Consumer Rights.

Companies are required to inform the department when they increase the prices of medicines. The department itself allows companies to increase prices by 10 percent every year for inflation, and by more than 10 percent when the price of raw materials increases, according to spokesperson KC.

Humagain said that there is no limit to the bonus--the medicines that are provided free of cost while purchasing large quantities--that companies offer wholesalers, dealers and retailers. Both Nepali and foreign pharmaceutical companies offer similar benefits, says Humagain. This bonus too is recovered from the customers via the inflated marked price of medicines.

Just how exorbitant the marked price is can be seen in the substantial discounts that are offered by low-cost pharmacies in government-run hospitals like the Paropakar Maternity and Women's Hospital, Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Manmohan Cardiothoracic Vascular and Transplant Centre, and the Bharatpur Hospital in Chitwan. But these pharmacies are not subsidising the medicine and eating the losses; they too make a profit, said Gautam of the Paropakar Hospital.

According to Narayan Dhakal, former director-general of the Department of Drug Administration, there is no evidence to show that high prices of medicines are linked to the actual costs of research, development and manufacturing. Instead, inflated drug prices are a result of drug manufacturers attempting to recoup their investments in pharmacies and doctors by passing it on to the customers.

Pharmaceutical companies too admit to this. According to Biplab Adhikari, general secretary of the Association of Pharmaceutical Producers of Nepal, companies inflate the maximum retail price as they have to spend large amounts in promotional activities like hiring medical representatives to advertise their products to doctors.

“We have to provide training to medical representatives and pay them salaries,” said Adhikari. "There are also transportation costs, rent of storage units, manufacturing costs and bank interest, all of which contribute to the price hike.”

Adhikari sees nothing wrong with marking up medicine prices to recoup investments in other areas. After all, that is what businesses do. But the massive markup for medicines, something so crucial to human health, is a cause for public concern, say consumer rights activists.

A lack of oversight

In India, the price of drugs is monitored and regulated by the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority under the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilisers. The authority decides the prices based on the Drugs (Price Control) Order of 2013. Prices cannot be charged above the maximum limit decided by the authority and new drugs are consistently added to the list.

India’s Bureau of Pharma Public Sector Undertakings has also launched a programme to “bring down the healthcare budget of every household by providing quality generic medicines at affordable prices.” Under this plan, generic medicines are usually cheaper by 50 to 90 percent of the average price of the top three brands of the corresponding medicine.

Compared to India’s robust legal framework and ambitious plan to prioritise generic medicines over their expensive, branded variations, Nepal’s administration is woefully inadequate.

According to the Department of Drug Administration, there are over 21,651 registered pharmacies in the country but the actual number is estimated to be much higher, as many are operating illegally.

In order to monitor these thousands of pharmacies and the medicines they are selling, there are 38 drug inspectors, according to KC, the department spokesperson. These inspectors don’t just inspect pharmacies and drugs but also have to do the official bureaucratic work of preparing reports and taking action against those found guilty. This has overburdened an already small force of monitoring officials.

Pan Bahadur Chhetri, the director-general of the Department of Drug Administration, concedes that the drug market is not fair and that his office has not been able to strictly regulate drugs and their pricing.

“Due to budget constraints, a lack of human resources and some legal hurdles, we have not been able to do the work as per the public’s expectations,” said Chhetri. “The department alone cannot control prices as the existing law promotes an open market.”

Currently, all the department does is randomly collect samples of a few medicines and carry out tests in its own laboratory. As the law does not mandate fixed prices for medicines, it is not illegal, even if it may be unethical, for companies to set high retail prices. So the department is powerless to act, said Chhettri.

According to Chhetri, the Ministry of Health and Population needs to come up with a new law to control the price of medicines like in other countries. And it also stressed the need for all state-run health facilities to operate their own pharmacies, instead of contracting them out, to provide assistance to patients.

Doctors, too, agree. According to Dr Dipendra Pandey, chairperson of the Government Doctors’ Association of Nepal, if the Health Ministry sets the maximum retail price of medicines, all corruption and collusion between the different agencies in the drug markets will stop.

When the Health Ministry started enforcing hospital pharmacy rules, in the last four years, most state-run health facilities have set up their own pharmacies, said Pandey. Since then, fewer representatives of drug manufacturing companies are visiting hospitals and pharmacies to offer deals, he said.

At the mercy of doctors

At the heart of this insidious network between pharma companies and retailers is the relationship that companies cultivate with doctors--the ones who prescribe the medicines. Pharmaceutical companies influence doctors by providing them with incentives, which can range from free lunches to all expenses paid trips abroad. This kind of ‘investment’ in doctors is recovered from the high MRP set for the medicines that these doctors are encouraged to prescribe.

A practicing doctor, who spoke to the Post on condition of anonymity, attested to the fact that these malpractices are rampant in the medical field. The doctor, who pursued his Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree from BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, said that drug manufacturing companies provided free lunches for all medical students while he was at the institute.

“Medical representatives from various drug companies would approach us and ask us if we had anything we wanted,” said the doctor. “From the moment we are enrolled in medical school, they begin influencing us by offering stationery or other student requirements.”

In return, the medical representatives ask doctors to support them by prescribing medicines from their companies, he said. Such offerings depend on how popular and renowned the doctor is. More renowned doctors get bigger benefits, like airplane tickets to attend seminars abroad, cars, electronic gadgets, and rent for their private clinics, said the doctor.

Drug manufacturing companies also organise doctors’ conferences or give tickets and money so that doctors can take part in such conferences, according to a number of doctors the Post spoke to. Companies recover these costs by pricing their medicines in such a way that ensures a substantial profit.

Medical representatives also try to influence doctors through their seniors or faculty heads.

“The head of our department used to approach us personally and dictate that we prescribe medicines from a particular company,” said the doctor. “They would even threaten to give us lower marks in practical subjects if we did not comply. Why would they do that if they did not have a personal interest in a particular company?”

In a market economy, consumers have the right to choose goods and services, but when it comes to doctors, patients are often boxed in to the expensive branded medicines prescribed. Doctors, under the influence of pharma companies, ultimately decide what medicines patients will consume.

Dhakal, the former drug administration official, said that patients are not in decision-making positions.

“Patients do not have the right to choose medicines as doctors and retailers decide and take undue advantage,” Dhakal said. “When it comes to medicines, consumers do not determine the price.”

According to Dhakal, doctors even prescribe supplements that patients might not need or expensive versions of medicines over their cheaper alternatives.

“What is the need for multiple antibiotics when a single antibiotic will do the same work,” said Dhakal. “When oral drugs are working, why are patients being given injectable drugs?"

Humagain, the consumer rights activist, too said that despite the availability of cheaper medicines, doctors often prescribe branded, imported medicines that are more expensive. Patients are generally unaware of the availability of cheaper alternatives and trust their doctors to prescribe what is best for them, unaware that doctors are benefitting the prescription, he said.

According to Pandey of the Government Doctors’ Association of Nepal, the Nepal Medical Council allows financial or other support for academic activities and it is the same all over the world. The Nepal Medical Council is the government body that regulates medical education and takes disciplinary action against doctors in cases of unethical behaviour or malpractice.

Dr Bhagwan Koirala, who is the chairperson of the Nepal Medical Council, said that the council is clear about ethical practices and guidelines for medical practitioners.

“Accepting financial support for the promotion of academic activities is acceptable, as this also helps the academic growth of doctors,” said Koirala. “But taking personal benefit is illegal and unprofessional. The council is working to crack down on such practices.”

The most effective way to prevent these anomalies, said Koirala, would be for the Ministry of Health and Population to ensure fair prices of medicines by setting a maximum retail price on its own. There can be no compromise on the quality of the medicine so the Department of Drug Administration needs to be able to scrutinise and ensure the quality of the medicines once the ministry sets a maximum price.

Likewise, patients also have to pay exorbitant prices for surgical tools and devices used in the treatment of orthopedic problems, cardiac devices and others. These too are very expensive and no one is monitoring the price and quality of such devices, said Koirala.

“Everyone knows that there is a significant margin in medicine. This is practiced across the world,” said Koirala. “Drug manufacturing companies spend large amounts on promotional activities, and provide huge margins to wholesalers and retailers. But patients or consumers end up paying the price for those benefits.”

***

What do you think?

Dear reader, we’d like to hear from you. We regularly publish letters to the editor on contemporary issues or direct responses to something the Post has recently published. Please send your letters to [email protected] with "Letter to the Editor" in the subject line. Please include your name, location, and a contact address so one of our editors can reach out to you.

20.81°C Kathmandu

20.81°C Kathmandu