Fiction Park

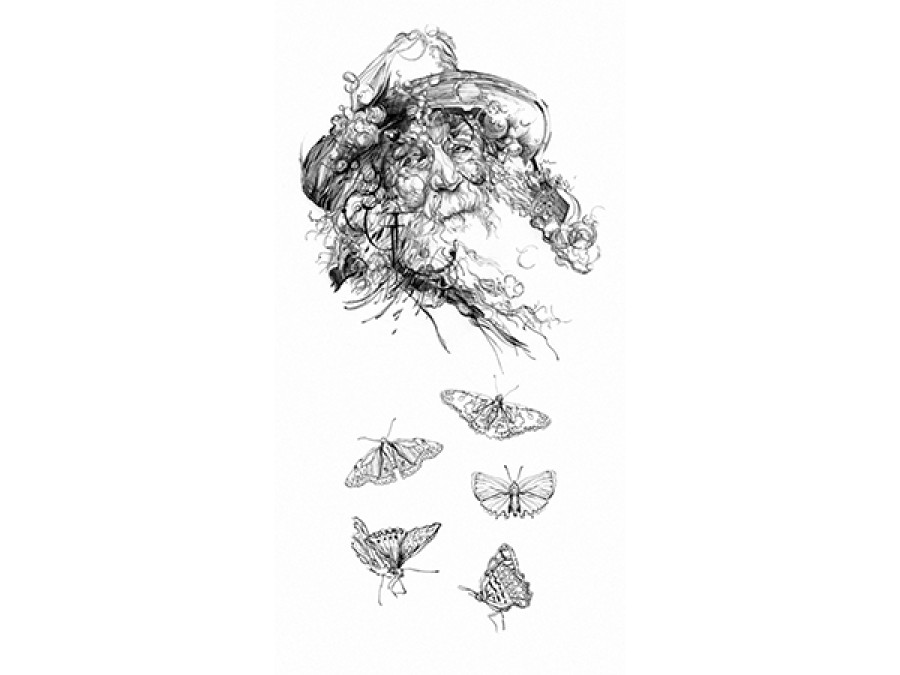

The Old Man and the Tea

An old man decides to start living when it is too late. He will try to find catharsis and himself

Chiran Raj Pandey

The old man has been here for too long now. He started off as an innocent help for Kantipur Java before it became the most reputed coffee place. The place was in

between a statue of Birendra—somewhere in New Road—and a huge building called the Simrik. When a lonely writer’s daydreams turned into a successful business that turned into a chain of coffee places around the city, that place in between Birendra and the Simrik became a place that smelled of coffee and cigarettes by the day and the sweat of a young old man who fought with his longing for death every minute to make an espresso for that young kid with a beard and a book.

In his ‘40s, in the ‘80s, Kantipur Java turned into a sea of rats gnawing at each other for a slice of meat. The employees turned against the employers, coffee turned into rat shit and the old man—then young—lost his love for the stench of caffeine. There was an earthquake that turned buildings upside down and the minds of the people that inhabited these buildings no longer responded to the human consciousness with congruency. Kantipur Java, a place where love grew within love (and coffee) and the people turned to each other in their times of non-need, became the dystopian version of itself. Birendra and the Simrik closed in on each other and the king finally showed his true colours.

The old man was driven into something much worse than insanity then. Day and night, he licked his fingers that still held onto that caffeine stench. He didn’t shower for weeks, days, years, months—chronology was no longer important. He longed for love, and he had always found love at that one coffee place that betrayed him. He no longer cared for coffee; the once magazine-filled shack in which he lived burned down in a careless attempt to let go of himself. He longed for love, he longed for love.

He thought he would find love in death. He tried several times, but each effort culminated in bringing him closer and closer to life. His was not a life that was meant to be ended. When he tried to burn his shack down (along with his self), he fell asleep, only to find himself waking up in the middle of Tundikhel, a cigarette in hand and a bottle of beer in another. Another time, he downed 25 acetaminophen tablets—these would surely take him out—but he later found out that he had been part of a clinical trial investigating placebo in treating mild headaches. Another time, he hiked an entire day to Nagarjun with a 05 Chinese Revolver tucked inside his underwear. At around midnight that night, he whipped out his gun, put it against his head, and pulled the trigger with such confidence; but the gun misfired and the bullet came out the wrong end, lodged itself into a tree. The old man cried himself to sleep that night—not the kind of sleep he wanted.

Soon enough, these absurdities turned into normality for the old man. He no longer felt sadness, he no longer longed for love. He no longer longed for death and death had never longed for him anyways.

The old man grew tired of

looking for ways to die. Death grew tired of telling the old man that death wasn’t for him.

Soon but not as soon as he had hoped, the old man lived his name. His hands became stronger and

then suddenly, weaker. The skin beneath his eyes sagged and his

nails hardly grew. He felt very few things with his hands and legs and he felt very few things.

Now that he was old, the old man decided that he needed to get back to living as much as he could before death took him away. All those years he had longed for death and now, when death was on its way, the old man wanted to live.

And so he opened a small tea shop in Tinkune, named it Diuso ko Chiya but it is open evenings too. It took off very well. Not as well as Kantipur Java, of course, but if Kantipur Java ended that way, what was well? The old man owned the place and the old man employed himself. He slowly staggered up the stairs with a tray of black and milk and chini and chini-nahalnus-dai tea every day. The men who walked in shouted out to the old man, but he already knew what they wanted. He could tell from the smell of their breaths. The cigarette smokers will drink milk tea because they need to get rid of the dryness that comes with Surya. The coffee drinkers will drink black tea because they need that unfiltered smell of caffeine that milk seems to mask. The milk drinkers will drink chini-nahalnus-dai tea because they’ve lived with the taste of bhaisi-ko-dudh since they were children.

The old man has quit smoking—

“Ek cup chiya dai.”

The old man has an itch around the area surrounding his groin that grows stronger day after day. It hurts when he scratches the itch, but he can’t do without scratching the itch. The itch calls for the scratches and the scratches answer. The corner between his groin and his legs has become a place for his fingers to regularly meet his skin in sheer hostility, unfiltered, uncensored. It hurts him, the scratching of the itching—but it is the only that keeps him going. It draws him closer to living—that one thing he did not ever want to do—and he feels alive when he scratches. As the skin breaks under his nails—he hardly trims his nails these days—a strange feeling liquid pours out. The old man thinks this is his catharsis, in liquid. Liquid means purity, he thinks. He will let out this strange feeling liquid until he lets out all the coffee he bled into those cups at Kantipur Java.

When a young man in his 20s or his 30s or his 40s wants a cup of tea, the old man makes it for him. He calculates carefully. He knows what water will turn into vapour when you heat it and so he puts in a little more water for every cup. He knows the sounds the water makes when it is time to add the leaves. He knows the breath the tea takes once it is ready to go into a cup.

At night, the itch becomes louder when the scratches become louder as the old man sends himself to sleep, alone, quiet in the darkness. When he feels it is time to let go, the old man boils a cup of tea and pours it into the craters his nails form in the corners between his legs and his groin. All that has ever happened in the world was good, he thinks; the water slowly trickles down his legs and into the abyss the ground forms beneath him.

The old man sighs.

17.45°C Kathmandu

17.45°C Kathmandu