Editorial

Same tricks, same results

Forming commissions and study groups is insufficient for the desired administrative reforms.

The Administration Reform Commission formed by King Mahendra submitted its third report on August 15, 1970. The report in its preface states that “a commission, committee or any other agency alone cannot achieve a stated goal [unless complemented by]... purpose-driven effort.” The commission drew the conclusion after studying the recommendations of past commissions and study panels and their impact in administrative reform. At the time, it had been around two decades since Nepal started practising the modern administrative system. Previously, successive governments had formed one after another high level commissions, including the one led by then prime minister Tanka Prasad Acharya in 2013 BS (1956-57), which too aimed at restructuring the country’s administrative system.

Really, over the past seven decades, Nepal has formed dozens of commissions and committees to study the country’s administration and recommend measures to improve service delivery. Yet administration and service delivery remains arguably the least reformed sector. In the past couple of decades alone, Nepal has witnessed several radical political changes. The country abolished the partyless Panchayat system and reinstated multiparty democracy in 1990, and then, in 2008, went on to abolish the kingdom to herald a federal democratic republic. However, the country’s administrative machinery continues to be largely dysfunctional. In many cases, the prime ministers of this republican system appear to be copying the (failed) methods of the Panchayat era.

A month ago, Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli himself formed a 15-member High-Level Governance Reform Recommendation Commission—also known as the Good Governance Commission—under his leadership. But the prime minister has not been able to convene a single meeting of the commission. Nor has the government done other basic things to give a message of transparency and accountability. For instance, the Oli-led Cabinet is yet to make public the ministers’ property details, a practice followed to promote transparency. When the prime minister formed the commission, the appointment of the central bank governor was delayed for weeks even as leadership void in the vital institution threatened to do serious harm to the economy.

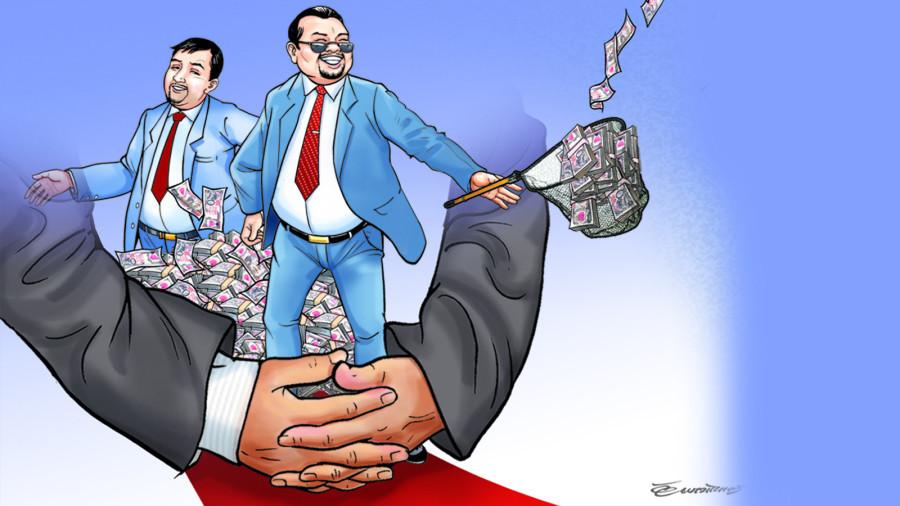

Over the years, whenever a serious issue is raised in Parliament or in society, piling pressure on the authorities to take action, the government forms a study committee or commission to douse the public ire. Many of these bodies cannot complete their given task. Even when they do, their recommendations are seldom implemented. This is why the formation of such commissions and panels have become a matter of joke: when there is an outcry on an issue, people predict, “Now, the government will form a commission!”

Notably, this age-old practice is now being copied by provincial governments. For instance, the Koshi government formed a High Level Administrative Reform Taskforce under the leadership of former government secretary Chandra Ghimire. (The body submitted a 244-page report on June 15, 2023.) Those in the political and administrative leaderships must internalise the message of the aforementioned 1970 report. In the five and a half decades since, the focus of successive governments has been to somehow divert public attention through gimmicks rather than to address the underlying problems. There could be no bigger indictment of our political and bureaucratic leaderships.

17.78°C Kathmandu

17.78°C Kathmandu