Editorial

Oli 4.0

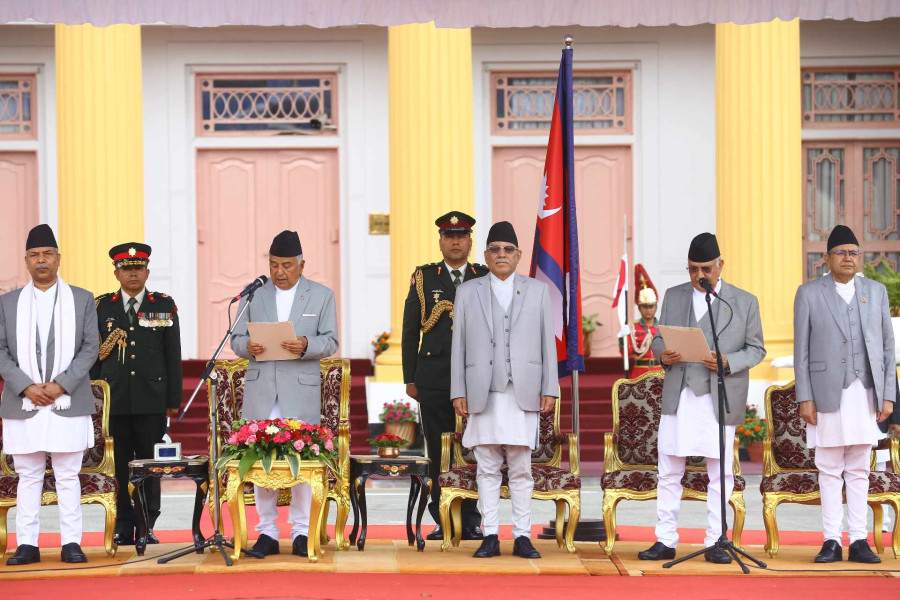

Has KP Oli really learned from his mistakes? The onus is on him to prove his critics wrong.

KP Sharma Oli begins his fourth term as prime minister with a bit of baggage. Most infamously, during his third term, when the time came to hand over his prime ministership to his coalition partner as earlier agreed, Oli chose to dissolve the House of Representatives—twice—rather than voluntarily give up power. Thankfully, the Supreme Court stepped in to avert an untimely election. Rightly or not, Oli has over the years built a reputation for wheeling and dealing and for surrounding himself with yes-men. He is not someone comfortable reaching across the aisle. In fact, his stubborn and acerbic nature has made it easy for others, including his coalition partners during previous terms, to take offence. At 72 and in iffy health, Oli is also seen as someone whose time in Nepali politics has come and gone. On the external front, too, challenges galore. In recent times, ‘China’s man in Nepal’, as dubbed by the Indian media, has had a difficult relationship with New Delhi. Of course, he must be lauded for taking a dogged stand against the 2015-16 Indian blockade. But then Oli started spouting all kinds of nonsense like claiming that Lord Ram was born in Thori of Nepal rather than Ayodhya of India, unnecessarily needling the powerful BJP establishment.

These are big hurdles no doubt. But they are not insurmountable. During the latest negotiations with Congress leaders, for instance, he is reported to have assured them that he has ‘matured’ and will refrain from taking juvenile steps like dissolving the House on a whim. He is also someone strongly wedded to the idea of a two-party polity, a strategy that suits many in the Congress just fine. (Whether it suits the country is a different thing.) As the agreement between the two big parties in the lead up to the formation of the new government is yet to be made public, it is hard to make definite predictions. Yet if Oli can channel his strong character to use the over two-thirds majority in the House for productive purposes, he can get a lot done. On India too, Oli was for long known as someone with personal rapport with top Indian leaders—and he still has the confidence and capacity to take personal initiative to mend fences. Disliked in Delhi and mistrusted in Beijing, Oli nonetheless will have his task cut out maintaining an increasingly difficult balance between the two neighbours.

The priority for the new Oli government, just like it was for its predecessors, will be to breathe some life into a stagnant economy. A message of political stability given through a two-thirds majority will help. Yet both in and outside the country, there is a justified suspicion over the longevity of this ‘unnatural’ Congress-Communist coalition. Oli as prime minister must be ready to make some tough personal adjustments in order to stop the cycle of instability in government. This means not just reining in his natural tendency to rebuff critics and rely on a small coterie on all vital matters but reaching out to coalition partners and even the opposition parties as often as he can. In fact, if Oli tries to go it alone, before long this coalition too will implode. Whether while trying to revise the constitution, making important appointments, or crafting a budget, his government must be seen to be striving to engage the widest section of relevant stakeholders. The onus is on Oli to prove his critics wrong.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu