Editorial

Deluge and disease

Learning from last year’s cholera outbreak, authorities should work to ward off waterborne maladies.

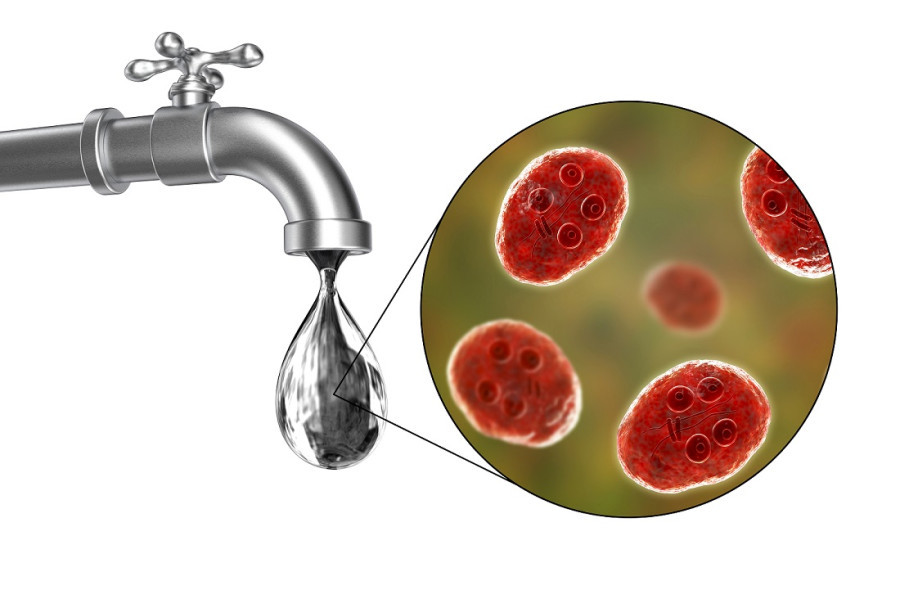

Monsoon is the most eagerly awaited of all seasons in Nepal, bringing with it the promise of plenty. But it is the most dreaded as well, as it also invites all kinds of hazards, ranging from floods to landslides, from vector-borne to water-borne diseases. Even as news of deluge and destruction get ample space in media and public discourse due to their tangible nature, water-borne diseases remain a silent epidemic. With monsoon rains wreaking havoc in different parts of the country, most drinking water sources have been contaminated by floodwaters. Leaks in the supply channels due to negligence make it easier for sewage to seep in.

Last year, Kathmandu Valley witnessed a cholera outbreak, with most patients testing positive for Vibrio cholera 01 Ogawa serotype. Cholera cases had been reported from Bagbazar, Dillibazar, Balaju, Balkhu, Sanepa, Kapan, Naikap, Kageshwori Manohara, Bhaktapur, and Jaisidewal as the valley faced a massive garbage collection crisis coupled with heavy downpour. A Health Ministry study conducted immediately after the cholera outbreak last year showed that almost 70 percent water samples in the Valley were contaminated with E. coli and faecal coliform—which constitute a significant cause for cholera, diarrhoea and other abdominal ailments. The anomaly, though, is not limited to the Valley, as the lack of water sanitation is a pan-national problem. According to a 2016 study by Unicef, the E. coli bacteria, a leading cause of diarrhoea, was found in 71 percent of all water sources and 91 percent of those used by the poorest people in Nepal.

Unsanitary food handling is yet another problem leading to illnesses. Just last week, 47 people, including children and the elderly, from Gokarneshwar Municipality of Kathmandu, were hospitalised with food poisoning. Cases of food poisoning make it to the news throughout the year, more so in the monsoon, and up to the peak festival season. Although not all cases of food poisoning are water-borne, there is often a correlation between contaminated water and the occurrences of food poisoning, cholera, diarrhoea and various ailments. And as one of the most vulnerable groups, children face the brunt of multi-stakeholder negligence when it comes to safeguarding our water sources. The Health Ministry in 2021 found that for every 1,000 children under five, 349 suffered from diarrhoeal diseases.

All of it boils down to negligence in protecting our sources—water or otherwise. With the government taking little interest in providing basic amenities such as potable water, people across the country, particularly in semi-urban and rural areas, are forced to make temporary arrangements to ferry water from the springs to the household taps. Developed without technical know-how, such arrangements often overlook basic sanitation protocols. The problem of poor sanitation was reported even in the famous project run by Dharan Municipality under Mayor Harka Sampang’s leadership. Despite their best intent, local initiatives and government projects alike often neglect safety concerns as their only focus is to get the water running down the tap. For the good of the larger public, this must change.

With last year’s alarming cholera outbreak and the experts’ warnings about imminent water-borne diseases, the government should gear up this year, as the risk of an outbreak remains. It is high time all three levels created quality control mechanisms and rigorously monitored drinking water reservoirs. The three units of the federal government must act before the situation worsens and further stresses the country’s poorly equipped healthcare system. As it has a direct impact on people’s health, providing clean drinking water in monsoons should be a top priority.

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu