Editorial

Rich school, poor school

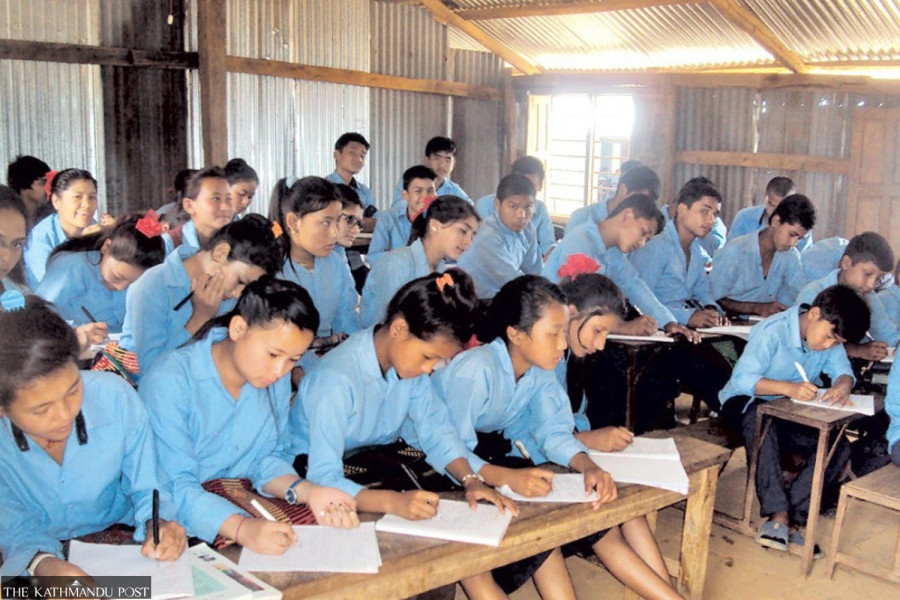

The steady decline of public school education portends a bleak future for the ‘socialism-oriented’ country.

The impending closure or downgrading of 23 out of 48 community schools in Tamakoshi Rural Municipality in Ramechhap is symbolic of the ills in public education that has engulfed the entire country today. As profit-oriented private schools aggressively take over the education sector, the number of community or government schools continues to dwindle, making education a necessary luxury. The decline of public schools is a result of structural problems in contemporary Nepal, ranging from discrepancies in implementation of federalism to problems of migration—and warrant both short- and long-term remedial strategies.

The first problem is the reluctance of the federal government to delegate authority to local bodies for the management of school education, as per the constitutional mandate. Schedule 8 of the Constitution of Nepal gives local governments the authority to manage basic and secondary education. Eight years after the constitution’s promulgation, the government is yet to register a bill to promulgate a federal education Act. This has precluded the handing over of the responsibility of education to the local level.

Procedural concerns aside, even where local levels have enthusiastically taken up the responsibility of managing schools, they have often failed due to a lack of financial and human resources. Most local bodies in Nepal lack trained personnel to oversee the functioning of schools, leaving the schools to be operated at their whims. We arguably have 753 different ways of managing schools now. Lack of financial resources as well as accountability on the part of the local bodies mean that schools that are not making money are shut down.

Moreover, the massive out-migration from rural to urban areas within the country and beyond has made it difficult for schools to get pupils. As English-medium schools, generally known as boarding schools, penetrate small towns, there are now few takers for public school education. The competitiveness offered by English-medium private schools has made it something of an unwritten code to send children there. Despite spending on human and material resources, most government schools across the country have failed to maintain minimum standards of education. Government agencies, not least at the local level, are least interested in uplift of the schools attended by children of poor parents.

Again, as the teaching-learning portfolio of public schools fails to improve, sending children to private schools has now been established as a necessity, apart from a status symbol. As a result, only the economically vulnerable parents are sending their children to government schools—and only most reluctantly. Education is, therefore, becoming ever more expensive, and hence a punishment, for Nepali parents. Combine this with the gradual entry of private sector education entrepreneurs often taking up major portfolios in the government, including at the Ministry of Education, and we have a recipe for disaster in the education sector.

The decline of public school education cannot go unhindered, as it portends a bleak future for the “socialism-oriented” country: The state cannot abdicate its most fundamental duty to ensure equal and equitable education for Nepalis of all stations. A positive step in this direction would be to expedite the enactment of the long-pending federal education bill.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu