Editorial

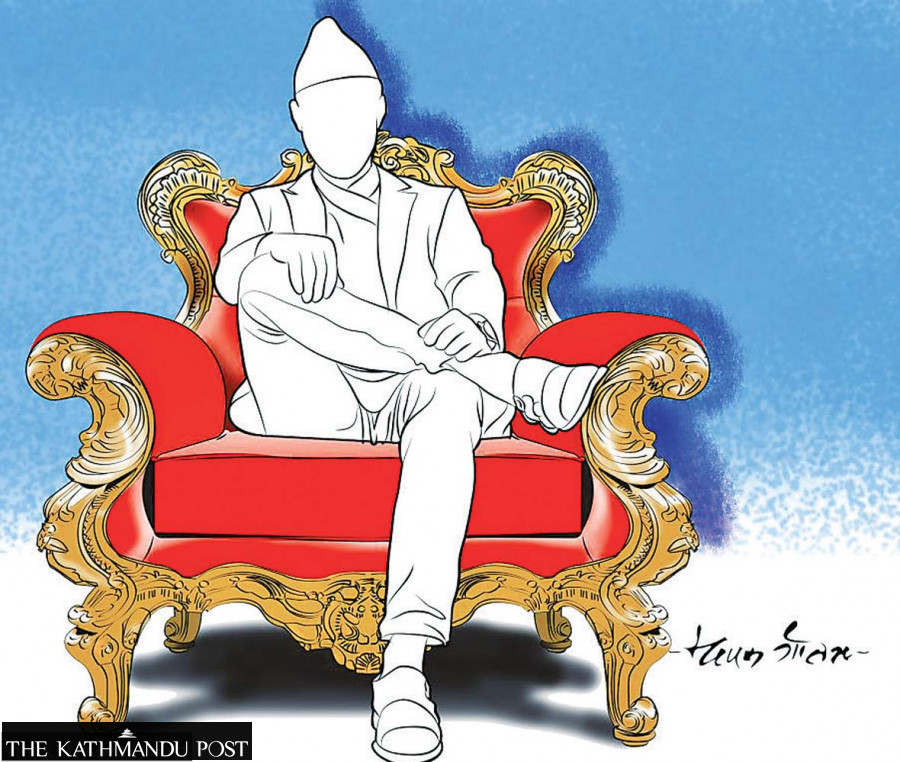

Deluge of deputies

Top leaders continue to prefer the symbolism of attractive posts to the substance of delivery.

The reckless distribution of deputy prime minister positions and the way some parties in the ruling coalition have refused to join the government after being denied ‘plum’ ministries are not signs of a stable, long-lasting government. The country now has four deputy prime ministers—with perhaps one or two more waiting in the wings. In terms of their roles and responsibilities, a deputy prime minister does pretty much the same things as a regular minister. There is also not much difference in terms of their pay and perks. Yet the partner parties in the ruling coalition have made securing a deputy prime minister for one of their own a matter of prestige. Given the country’s mixed electoral system, absolute majority of any one party (or two) will continue to be elusive. As such, Nepal’s federal governments will continue to be rainbow coalitions of parties from all over the political spectrum. And based on current trends, to manage such disparate coalitions, the prime minister will be forced into making all kinds of unwanted political bargains.

Such coalitions rarely govern well, with the prime minister struggling to hold the legions of his deputy prime ministers and ministers accountable. Moreover, as the government is held together by a delicate power balance rather than on the basis of some shared ideology or governing principle, there is always the risk of a rupture. In the past, all kinds of excesses have been justified in the name of ‘coalition compulsions’. In 2017, then Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba had appointed 54 ministers. Thankfully, the new constitution capped the number of ministers at 25. (Deuba could appoint so many under the pretext of ‘transitional provisions’.) Another favourite tool of coalition prime ministers has been to split existing ministries to expand their cabinet. Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal wanted to do the same this time before he was stopped on his tracks by growing public criticism.

Most of the new prime minister’s time, it appears, will be spent balancing a wobbly coalition, and he will have little time left to actually govern. For their part, the small parties have also betrayed a lack of self-belief in their bargaining for deputy prime minister. The likes of Rabi Lamichhane and Rajendra Lingden could easily have carried out their duties as regular ministers. Their focus should have been seamless service delivery and national development rather than to somehow, anyhow, secure the ‘ceremonial’ deputy prime minister’s chair.

At least another next couple of months could be wasted in political bargaining to give a complete shape to the government, and then to elect the Speaker and the President. In the end, who gets those posts will again be a matter of political give-and-take rather than the suitability of individual candidates for those positions. It’s never a good sign for a democracy when its top leaders care more about the symbolism of attractive posts rather than the substance of delivery. And people aren’t fooled so easily. The commitment of everyone from the prime minister down to cut unnecessary expenses sound hollow when they continue to bitterly fight for meaningless posts just to prop up their fragile egos.

14.12°C Kathmandu

14.12°C Kathmandu