Editorial

No small wonder

Even the emergent forces in Nepali politics seem ever-ready to sacrifice their cherished beliefs and public trust.

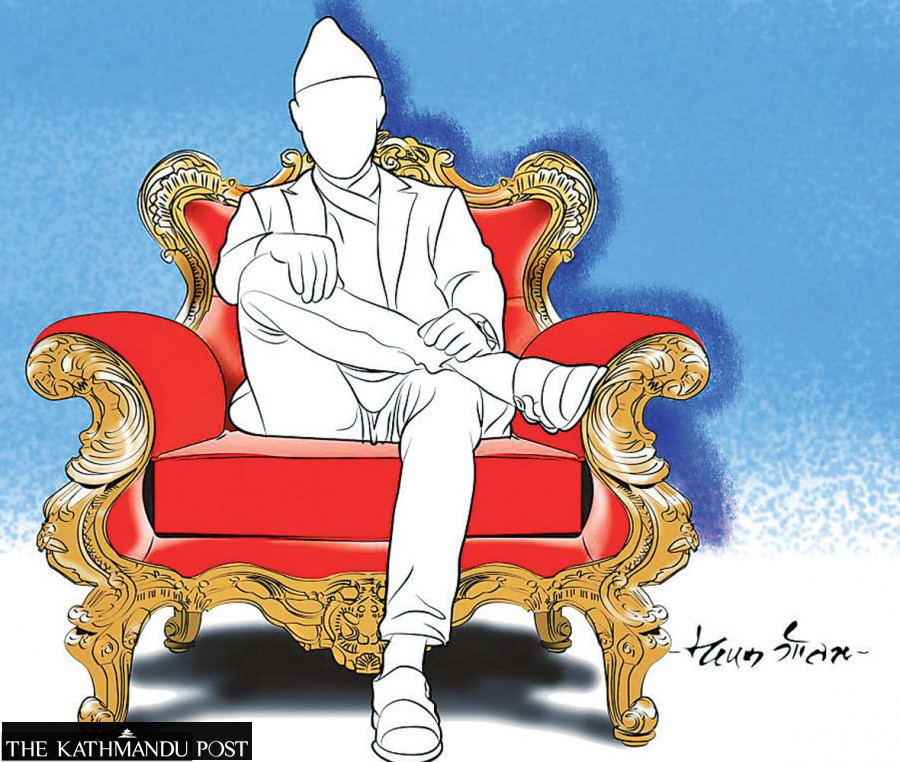

If something brings Nepal’s political parties together, it is their common desperation for executive power. Notwithstanding their differing ideological backgrounds and histories, they seem to be bound by an unfathomable greed for plum ministerial positions. What seemed nigh impossible just a month ago is playing out for real in front of our eyes—the coming together of the CPN-UML and the CPN (Maoist Centre). The term “communist” in the names of these parties is deceptive, for they are now yoked together in the new government not because of any ideological affinity or common vision but by the sheer lust for power. Even the smaller parties, especially the Rastriya Swatantra Party and the Rastriya Prajatantra Party, were eager to join the government. Nevermind that they were this time mandated to stay out of the government and to play the role of a constructive opposition. Not only did they not want to stay in the opposition, they seemed ever-ready to sacrifice on their core values to get to the government.

Rabi Lamichhane of the Rastriya Swatantra Party has taken a plum position in the government despite an apparent conflict of interest—which is already evident in the Kathmandu Chief District Officer’s response to the Supreme Court on the citizenship row, where it claimed the case against the new home minister is meaningless as it was filed by “irrelevant” people. Ironically, it took Lamichhane just six months to turn from a boisterous television anchor pushing for meaningful social change into a calculating politician who had no hesitation in joining hands with the same set of leaders he so bitterly denounced.

The Rastriya Prajatantra Party is still a confused lot. Not only did it support Pushpa Kamal Dahal’s Maoist Centre, a party with which it has a diametrically opposite ideology, it is also desperately bargaining for power. The Rajendra Lingden-led party is learnt to have asked for four ministries along with deputy prime minister. The most significant condition it has put forward for joining the government is a public holiday on Paush 27, the birth anniversary of Prithvi Narayan Shah. That a party with an undying fascination for monarchy would seek holiday on a day it considers auspicious is obvious, but its readiness to join the government upon the fulfilment of a trivial demand also suggests a kind of desperation.

The CPN (Unified Socialist) has as of now been discreet in bargaining for executive positions in the government, primarily because of its miniature status in Parliament and its failure to be a national party. Having failed to win the expected number of seats in the recent elections, it is now batting for “baam ekata”, or unity of the leftists. In reality, the party seems to be chomping at the bit to join the government, even as it maintains that it will not easily bow down before KP Oli, the leader of the biggest party in the ruling coalition.

As Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal prepares to seek a vote of confidence in Parliament next week, the smaller parties are openly clamouring for a piece of the government pie. The saddest part in all this is that even the emergent forces in Nepali politics seem ever-ready to sacrifice on their cherished beliefs and public trust. In prioritising executive power above all else, they are proving to be no better than the big parties they like to denounce.

13.2°C Kathmandu

13.2°C Kathmandu